Playboy closes his legs. I mean, doors. In the middle of last March, its current executive director, Ben Kohn, put his face of postcoital leprechaun before the cameras to affirm that, because of covid-19, the illustrious magazine of "entertainment for men" was finishing the paper edition and it became digital. I don't know if anyone was saddened by this fact. Playboy is one of those things from the remote past that, even considering that at some point they had a use, like the Transition singer-songwriters, one cannot imagine with current followers.

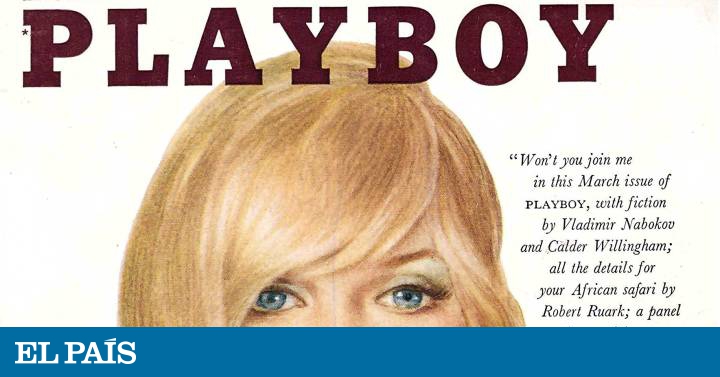

Even if no one mourned his loss, it goes without saying that Playboy is no longer what he was. When it was launched in 1953 by its founder Hugh Hefner (first cover: Marilyn Monroe in –snif– one-piece swimsuit), he yearned to be a classy and content magazine who was, at the same time, rogue enough to rival Esquire . Hefner, who grew up in a Chicago Methodist family, was a neat and cultured liberal with universal enlightenment plans. In one of his early declarations of principle (Hefner was missing the editorial weltanschauung ), the future icon stated that “we like to mix cocktails and a couple of snacks, put some background music on the phonograph and invite a well-known for a quiet discussion about Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex ”. Yes, reader, laugh out loud with pleasure. The word sex sticks its unsuspecting head behind the rock of Nietzsche, as if the previous mention of a grim artist was enough to strip it of all salaciousness. The phrase makes one think of those old ads for dildos in which the user was seen applying the dildo to any corner of her anatomy (armpits, cervicals, a nostril) that was not one of the significant ones.

Playboy would end up representing, over the years, the epitome of the affluence, sophistication and cool elegance of the time, but the eternal question remains unsolved: were elevated texts an excuse to show the greatest possible number of tits and asses? Or, on the contrary, those women in not-so-shameless pose (the first appearance of pubic hair was in 1972, and only because Penthouse , its new competitor, was being lined with intrauterine close-ups) were Hefner's way to disseminate quality literature among the common people? ¿ Mens sana in corpore libidinous ?

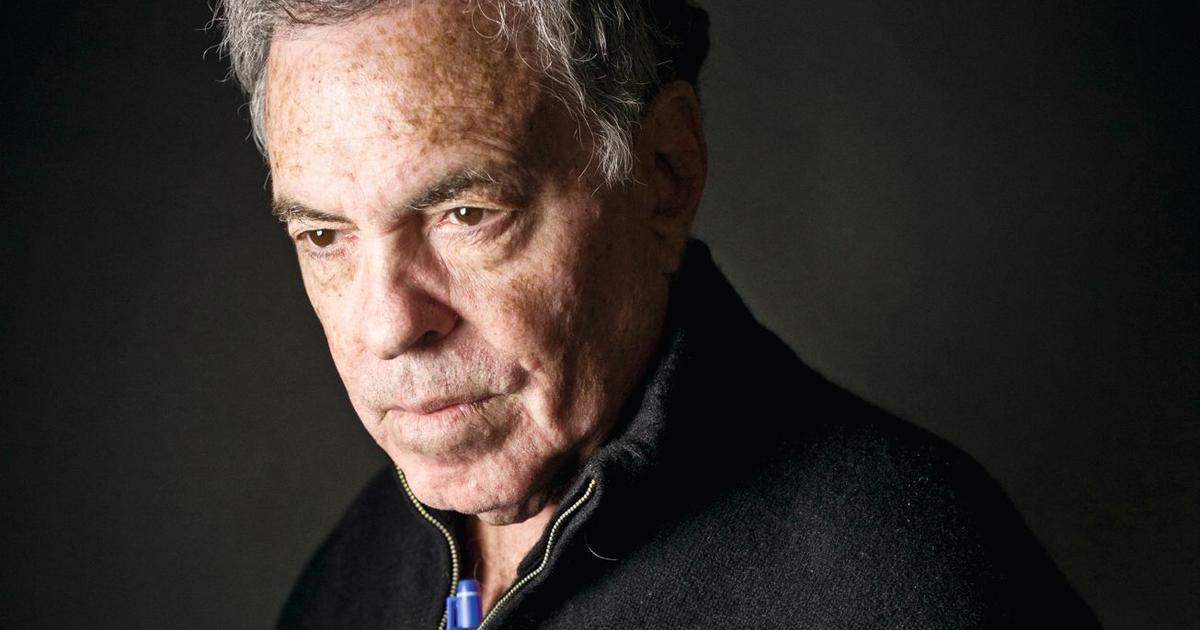

The cynics among you will say that the first, but this articulated journalist is not so clear. Although "feminism" was, for old Hef, a difficult word to spell (he claimed that breaking free from the shackles of sexual modesty was "good for women") and certainly its publication was, in the eyes of today's reader (and I suspect that also to then), sexist, the founder of Playboy was not Bertín Osborne. The 1970s transformed Hefner into a floaty, lubricious, almost conservative float (something that horrified him), but in the mid-1950s he was still the personification of the great reserve, connected and progressive hipster . He loved modern jazz and was a great reader, two aspects that the magazine, at least in its imperial phase, did not fail to reflect. He was also a fervent defender of racial equality, as evidenced by numerous interviews with black leaders and personalities: Martin Luther King, Cassius Clay, Miles Davis or Malcolm X, among others, went through his pages in verbose and empathetic interviews.

What set Playboy apart from the other monthly openings at the time was the number of A-list novelists who rubbed shoulders with their centerfolds . It is impossible to read a literary biography of the second half of the twentieth without encountering the moment of joyous toast that accompanied the letter of acceptance of the magazine. Playboy boasted the best rates in the industry (except, of course, when it comes to bunnies' wages ), but the real cache was immaterial: publishing there was doing it where the best, a sign of prestige in itself.

The “I buy it for the articles” thing became over time an inevitable joke, the ironic wink of Those Who Were Going to Shake it off, but, being fair, you couldn't use the same excuse when they caught you with the Lib under the jersey (I know what I'm saying). Grace worked because it was plausible. When opening the Playboy by any non-dropdown page, one came across the best signatures of the moment. Ian Fleming, whose prose was so ideal for Playboy that he looked like a robot created by Hefner, was one of his flagships, but Saul Bellow, Vladimir Nabokov, Doris Lessing, Norman Mailer, Margaret Atwood, Joyce Carol Oates, Kurt Vonnegut were also published there. , Joseph Heller, David Foster Wallace and Haruki Murakami. Not exactly feather weights. And Ray Bradbury, of course: Hefner himself decided to issue Fahrenheit 451 in installments, sealing his success. Sci-fi authors were always welcome, and both Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov made themselves comfortable in their pages (which no doubt explains why my father hid Playboys in the drawer of his underpants).

We can take Hef's most LOL statements with a pinch of salt (at a press conference in 1969 he unperturbed that "the essence of Judeo-Christianity resembles Playboy philosophy ") but it is indisputable that man was not alone in this for the wiggles. Painting him like an old green with avocado dermis that ran, like a priapic faun, after the bunnies in his attic would be logical, considering his hobbies and his character, but would ignore his cerebral side. In 1978, at the party celebrating the magazine's 25th anniversary, Hefner took the microphone and, addressing the bunnies present, said: “Ladies, it has been a wonderful 25 years, and I owe it all to you. Without you I would have only had a literary magazine. ” Perhaps the answer to the eternal question lies in your sentence.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/3J6DCILJR5DX5LBCZFVPLETXL4.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/VBZMURLLFRAH3DCSBFQHOAECPI.jpg)