The intellectual contradicts other people, the sage contradicts himself. This variation on an Oscar Wilde maxim can be applied to the cosmopolitan. The cosmopolitan somehow insists on the habit of contradicting his national identity. Someone said that whoever does not know a foreign language does not know their own. Going out allows you to see things from outside. In my first stay in India I kept thinking about the imprint of Christianity in European thought (Marxism and positivism). I had never found myself outside that sphere of influence and the displacement allowed me to see our civilization (that intersection of Hellenism and Judaism) from outside. Since then I have lived in Asia, America and Europe, and spent long periods in Africa. Everywhere I have seen (in addition to caravans of sadness) genuine and imposting cosmopolitans.

Well understood cosmopolitanism was that of the cynics, the dog sect, who laughed at the wishes of the common man and were naked of prejudices for life. The spurious was that of the enlightened, whose epitome is Kant. Unfortunately, today the latter predominates. Diogenes is said to have invented the term. When asked where he came from, he replied: "I am a citizen of the cosmos" ( kosmo-politês ). He did not say of the planet or of this social class, he said of the cosmos, which for him, as for the ancients, was complex and had various planes of existence that could be visited in dreams or meditation.

But Diogenes did not anticipate globalization, enlightened people who barely left their rooms anticipated it. That attitude of the cynics was shared by the Stoics. Zenón the Cypriot, its founder, said: "We consider all fellow citizens and compatriots." Cosmopolitanism was born as a vaccine against nationalism and with a wandering vocation: the homeland in sandals. In time, the Enlightenment would confuse it with universalism and that moment was distorted. He launched the aspiration to a universal language (mathematics, scientific English) in which meaning did not depend on the constitutive features of a particular culture, but was common to all of them. That was and continues to be the recurring obsession of the dominant cultures, which tend to impose their meanings beyond their own borders, until extending them, if possible, to all of humanity. As if the sense was possessed by an anxiety that led him to exceed his own limits. Cynics in the dog sect led a wandering life precisely to flee from these imperial ambitions. But everything was done with the best intention. As if threatened by a pandemic, Kant led the way towards universal legislation and a common destiny for mankind. But the supposed "perpetual peace" hid the imposition of models and the domination of the strong state over the weak one. It was the starting gun towards globalization, which, under the mask of tolerance, propagates a single currency, a single language and a single way of life (coincidentally those of the empire). The enemy of the cosmopolitan is the Puritan customs man. Kant, in a sense, was. He grew up in an artisans' guild and barely left Königsberg. He met all the conditions for enlightened delirium.

Morality and bourgeois customs ruin the enjoyment of the cosmopolitan, whose prerogative is distance, not being scandalized by anything, putting himself in the shoes of the other and laughing at both his own and others' custom. Some naive (or perverse, depending on how you look at it) continue to dream of that state that encompasses the entire human race, without knowing that they are projecting the worst nightmare. Your way to hell is full of good intentions. Hell is erected when the cosmopolitan spirit becomes ideology. Considering that all humans are under the same moral standards is not only dangerous but deeply unfair to the history and culture of peoples. Whatever the truth, various times and places present it through vivid symbols. The truth (and the vertigo) of the cosmopolitan demands fidelity to all those lives, ancient and modern. Those symbols direct the mind towards something that transcends them. If that something exists or is empty it does not matter, what matters is the life of those peoples and those individuals.

Kant's dream, paradoxically, makes cosmopolitan life impossible. Cancel the surprise and amazement at the extravagances of mankind. That life has little to do with the tourist predation that covets visiting as many countries as possible to bedecked in future gatherings. You can be cosmopolitan without leaving the library (Borges was) and provincial without stopping traveling. The spirit of the cosmopolitan is governed by hospitality and risk. Know the anthropological vertigo, stay to live among the locals and try to understand them. Welcoming the other, with his strange and incompatible way of life, in the understanding, can lead, if one deepens it, to alienation. The earth moves underfoot and the assumptions assumed during a lifetime are broken, unleashing anthropological vertigo. But to these risks are added some pleasures. One of them is to recreate in ways of life that are crazy or extravagant, but that the locals see as the most natural thing in the world. The cosmopolitan does not aspire to reduce the genius of the foreign culture to that of his own, but recreates himself in diversity. When the commotion is not great, that strangeness arouses the ironic smile and the investigation. If the cosmopolitan does not investigate, he derives into a snob, that is, a cosmopolitan cat, who imitates a distinction that he does not have and feels in the center of the world just because he lives in New York.

There was an Illustration that was not limited to the classrooms. An illustration that we have lost and that has only been partially recovered by the anthropological tradition. Hume and Leibniz, who were from the provinces, were two great cosmopolitans. Both fell in love with Paris, the most seductive and cosmopolitan city. Spinoza, who was born in Amsterdam (a nation of mariners and merchants), barely moved sixty kilometers around, but knew how to get out of his hall, which in his case was the synagogue. Heidegger is a good cosmopolitan and imposting provincial example, delighted to have met in his Black Forest. Nietzsche traveled through southern Europe, but was too sullen to be cosmopolitan. Like Heraclitus, he preferred the shelters and caves to the bustling streets of strange cities.

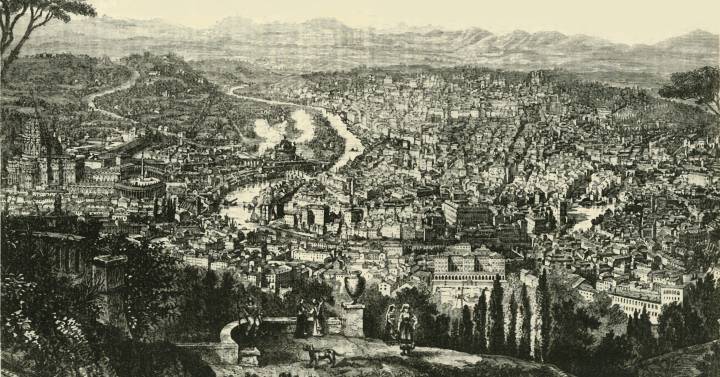

Despite today's profuse air and data traffic, Antiquity was a more cosmopolitan era than ours. Early Christianity, which emerged among the poor and insurgents, had a cosmopolitan vocation, sponsored by the genius and madness of Pablo de Tarso. Gentile among the Jews and Jewish among the Romans, he insisted on the brotherhood of the human race and on belonging to the world as citizens of the world. Buddha renounced that his teachings be kept in Sanskrit, the sacred language of his time (as scientific English is today) and allowed his message to be distorted by translation into local languages, some primitive. He let his teaching assume the genius of other languages. One of the most cosmopolitan philosophies I have ever known belongs to some severe ascetics from ancient India, the Jains. These apostles of nonviolence held that truth was never on one side and that all philosophy had its truth. They forbade themselves to stay more than three days in the same village so as not to adapt to their customs. Of course, this is an exaggeration. Continuously leaving everyday life is exhausting, but sharpens perception. One of the best examples of a genuine cosmopolitan was a countryman from Ampurdán. When Josep Pla liked most when he arrived in a new city, he went for a walk (without maps or guides), to observe the faces of passers-by. The cosmopolitan genius senses the wandering nature of the human condition and, despite the vertigo, is encouraged to walk on its various skins.

Juan Arnau is a philosopher. His latest book is History of the Imagination (Espasa).

READINGS

The cosmopolitan tradition. A noble and imperfect ideal. Martha Nussbaum. Paidós

The Europeans. Three lives and the birth of cosmopolitan culture . Orlando Figes. Taurus

Cosmopolitanism and the geographies of freedom . David Harvey. Akal

The vertigo of Babel. Cosmopolitanism or globalization . Pascal Bruckner. Cliff

The wreck of civilizations . Amin Maalouf. alliance