Lidia Godoy de Domínguez

08/28/2020 - 22:00

- Clarín.com

- Society

When my grandmother came to live at home it was magical to get closer to her. The respect that we should have towards the elderly was all powerful: their words seemed as sacred as their presence. I realized that it was difficult for her to leave her place in the field, in Pirayú, Corrientes; the province where we resided, but he also enjoyed each one of us a lot as a family.

I kept reading

He used to say that it was a "mission" to come see us and share his time with us. In the naps, the moments became unique when listening to their stories until sleep overcame me and sometimes I was left with the story unfinished. When I woke up and asked her the end of the story, she would tell me again, only if I finished my homework.

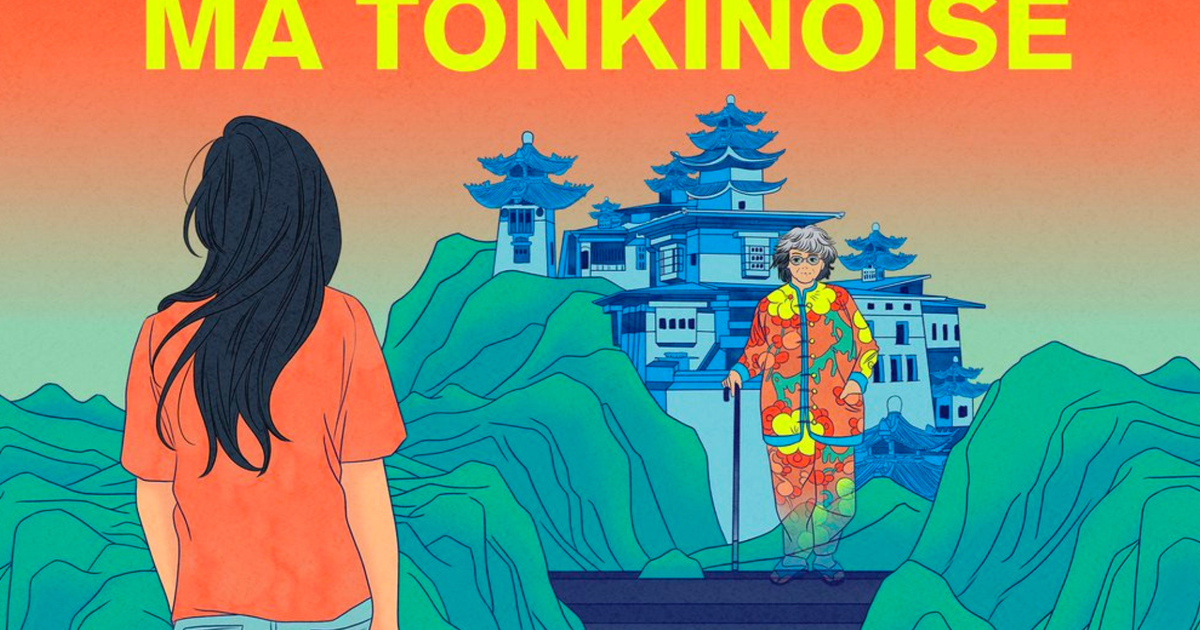

The grandmother, Rosario Pérez. A unique image

She had a wonderful way of narrating . She did it with her own particular tune in Spanish and then she would refer it again in the Guaraní language. The Guaraní showed, in her voice, a very sweet, peaceful, enthusiastic, expressive and poetic accent. The hours did not have time when he told me about the meaning of words and it seemed to me to enter another dimension of the world.

The first thing I learned was that I was "a daughter of affection", mita'i , because that is the name given to children in Guarani, that the mba'e pa reikó greeting in the morning was a question about " how was my soul ”. And then with great tenderness Mbae pa neko'e asked me again , "How did you wake up ?" and that my answers were ambú : "the sounds of the spirit of a girl".

Lidia Godoy when she was little, all smiles.

When she called me, she summoned me close to her saying eyumí ; The single word had so much spirituality and affection that it cannot be translated into Spanish; It is like a call, a spiritual approach towards a girl , expressed with a diminutive so affectionate, so tender and poetic at the same time (I came with me a little, something like that). Never did the afternoon “thunder” in the jungle of the Aguapey River (which was the immediate context of where we were) had so much sound with its echo in the distance and its Zununú name in Guaraní.

Never did the festive song (purahei ) of the little horner in the trees correspond so much to the gratitude of the warrior (Guaraní) Jahé to God ( Ñamandú eté ) for the realization of his love, previously “unrequited”. That was the reason why I remember asking him, many times, to learn his language. She had the habit of imprisoning me against her body and telling me the same key every time:

-To learn Guaraní, first I learned Spanish, I studied Spanish, I maintained its knowledge. Don't do the other way around !!

As a teenager. Lidia Godoy looks at familiar images.

It was like the whisper of an inspiring guardian angel to my ears, said in a weak voice, with fear, with distrust, with care that the sacred was preserved, with immense pain since he was denying me his own mother tongue , with anguish and a loneliness as great as that of an entire continent. In Corrientes there is certainly another country because we have inherited that philosophical principle from the Guarani themselves, the ancient "warriors", called the Ñanderecó which means "Our own way of living, our genuine way of being." And that heritage is sacred.

But the teachings and the moments shared with my grandmother were forgotten in the face of the strong influence of the Spanish language. And some words were devalued in the face of an unknown context. The single word "girl" that alluded to my identity had the strong importance of being classified as a kind of noun that responded to an extensive semantic scheme that had to be learned by heart.

That word in Spanish felt more distant, I saw it written in school books as a reference to other children, those in texts in Spanish. I thought she didn't name me. I did not see the writing of mita'í (as my grandmother called me with so much affection and affection). From my childhood I remember the severe verbal corrections of adults when I used a word in Guarani and also when I used a word in Portuguese (my town of Alvear, is on the border with Brazil).

Only once, after my insistence, was my grandmother decided to tell me that:

- "The" rounds "of the authorities happened when you least realized it, they entered your house and observed carefully that you did not speak in Guarani - he told me. I felt her fear when she told me those details, in addition, later she did not want to talk about it. I tried to know more on other occasions, but he only let me perceive the terrible fear that caused him to talk about it.

According to my father's stories, the “rounds” were patrols that were carried out on horseback, with armed personnel. Those were difficult times for the survival of the Guaraní language. The elders spoke in secret and the children were instructed in the denigrating character of Guaraní, especially its phonetic force. The school teachers had the power to whip children and shame them if they spoke in Guaraní.

My grandmother told me her stories repeatedly and the one she most enjoyed hearing was that of Arabury, the chief chosen by the tribes and the payé (priests) of the Guarani to hand over their lands to the Spanish conquerors because if they resisted they would be exterminated along with the language.

I liked listening to the moment when the warrior descended the ravines of what is now the capital Corrientes, with an entourage of virgins who carried offerings for Juan Torres de Vera and Aragón with their different clothes and their men with shining weapons in the sun. And how the Guarani saw Arabury cry, as he walked towards the conqueror. I once asked her if she knew what happened to Arabury. And she answered me that her soul was taken to Ñamandú eté (Supreme God) by a hummingbird, after it had stayed in the flowers of the orange groves.

A council of elders chaired by the Guarani payé (priests) had received prophetic visions of the coming of the Spaniards to Taragüí (Corrientes) before they arrived and had seen that they possessed very powerful weapons, capable of exterminating them all with what they would lose. most valuable thing they possessed: the transmission of the sacred Guaraní language. They decided, therefore, to receive them with hospitality and to act as guides and baqueanos in the knowledge of the places, so that the language would not perish.

Before going to sleep, I remember her laying her hands on me and repeating a phrase in Guarani, almost secretly: ÑandeYara rovazavá (May God bless you). My grandmother was then in the care of my aunt Isa (Isabel Godoy), in the city of Santo Tomé, Corrientes. I left my town -as most generations that finish high school do in the towns- to study Spanish. It was the year 1982, marked by the Malvinas War.

She passed away without being able to teach me more about the Guaraní language. It was a huge loss, not only for my family but also for the life of the language. I believe that his soul was also carried by a hummingbird to Ñamandú eté , after he was in the orange blossoms. Since then, I have dedicated each of my passed exams to her : “For the sweet cheerful lady, Rosario Pérez, to whom we affectionately called,« Grandma Charito », who stood up when asked about her homeland «Paiubre» (in Mercedes, Corrientes) and enjoyed the chamamé «La caú» ”.

Over the years, I not only realized that my dream would never come true: that of obtaining, in addition to the title of Spanish teacher, also the title of Teacher in languages native to my country. I also know that the educational system in Argentina is far from the modifications it needs. Historically, during the dominance of the Jesuit Missions in the territory (in which my town of Alvear was a Rest Chapel -founded by the priests of the Society of Jesus- called “Santa Ana”) the Guaraní language was the official language, used as an instrument for the expansion of the western Christian religion in these lands. In 1767, King Carlos III, expelled the Jesuits from America and since then Guaraní has been banned.

However, since 2004, Guaraní has been an alternative official language in the province of Corrientes . In this regard, I believe that we need the institution of a strong language policy in the province that allows us to rebuild our own identity from the Guaraní language. Fundamentally understand that we have our own dialect variety, the one called by the country's most prominent linguists as “Guaraní Corrientes”, compared to other dialects of the language in the country and abroad, such as Guaraní in Paraguay, with the that ours has marked differences. We need to establish teacher institutes in "Guaraní correntino" and promote their dissemination in schools of different levels and modalities and not promote the Paraguayan dialect. Currently, I have been trying to speak my grandmother's Guaraní fluently for some time , trying to reconstruct it and rebuild myself in that process , knowing myself as if she had never seen me, studying me from the most extreme strangeness…. And it is a painful process.

Pain emerges when I realize that many times I express myself in Spanish but I think and feel in Guaraní, that my provincial tune contains the precarious and primordial way of how the Guaraní tried to pronounce Spanish for the first time.

Pain arises when I read that for Spanish my grandmother's sacred stories are "legends"; rather, they are "unbelievable imaginary stories." The pain emerges when I realize that the word "guaraní", among some of its meanings, means "warrior" and that they continue to fight with their sacred voices inside me because although the war is odd, compared to the ruling Spanish , the Guarani are incredible warriors who fight omanó mbotá pevé (until the last breath of life).

After the pain, tears invade me and my tears are like the very rain of the jungle; as intense as it is momentary, so ancient and current at the same time. My cry is the rain of the jungle, more than five hundred years ago. My cry has no name, it is enormously anonymous.

Only when I write in Guarani does my soul stop crying with sadness and the anguish is transformed into a sacred joy, I feel the words haunt me and I am narrated by the most beautiful avañe'e (language of the people), I feel the primal voices, founders and epics of the Karibé (Great Lords), of the Ñe'engatú (those of the beautiful language), of the Kainguá (those of the song of the mountain), the Mbya (the people), all related by the sacred words that have soul and that constitute the Guaraní Nation. They all go inside me like a crowd crowned with feathers, running with bare torso, bare feet, after winning one more victory, with tanned skin, against the light of the sun rays of America, with their garlands and their flower bracelets ....

Finally, when I finish my writing in Guaraní, I am a warrior on my knees, with her quiver empty of arrows on the ground, in some opuy (sacred temple) of the open nature of the "Taragüí" (Corrientes), sounding the mimbiretá (instrument of wind), paying homage, with his weak Guaraní voice to Ñamandú eté (Supreme God) in festive gratitude, placing the showy crown of feathers as a trophy. And then I feel that the sweetness of the voices in the memory of Nature and the human soul, resist the most invasive pain.

----------

Lidia Godoy de Domínguez is a native of the city of Alvear Corrientes. She lives in Rosario. She is a Professor in Spanish and Latin Language and Literature and postgraduate in University Language and Literature (UNR). She holds a Master's degree in Linguistic Theory and Language Acquisition (UNR). the Literary Anthology "Renaissance of America", the "Latin American Letters" award for ranking the Dictionary of Latin American Writers and Poets with their participation. She also received the first prize in the contest "Short Story: Galician Roots" of the Galician Center of Rosario.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/YNKYBGQUB5D53NPUZ3EIDMK5OQ.jpg)