Jayro Bustamante, in 2019 on the set of 'La llorona'.

The career of Jayro Bustamante (Guatemala City, 43 years old) has not been exactly easy.

Film director in Guatemala, a country with little audiovisual industry.

Like many Latin American filmmakers, Bustamante started out in advertising, directing commercials.

Like many Latin American filmmakers, the Guatemalan emigrated to Europe to further his studies, and for that reason he lived in Paris and Rome.

Some of his shorts had a festival journey, he even worked on

stop motion animation.

And in 2013 he made a risky decision: his first feature,

Ixcanul,

It would be in cachiquel, the language from Mayan in which half a million natives of Guatemala speak, the main actors in that drama.

In 2015, the film competed at the Berlinale, won the Alfred Bauer prize, launched Bustamante on the route to the great competitions and even qualified for the Oscars.

The entrenched violence shown by Latin American cinema

In this way, Bustamante was able to aspire to a greater challenge, complete a trilogy that only existed in his head, and that's how

Temblores

and

La llorona arrived,

both last year.

Due to the pandemic, they now premiere in Spain:

Tremors on

Friday and

La llorona

on November 13.

“I almost prefer to call it a triptych of insult,” says the filmmaker.

"They are the most common in my country."

Although he warns below.

"The films are not made to show the problems of discrimination that overwhelm us, but rather they reflect the pride of the Guatemalan in being who he is, a pride in not making progress."

The first insult, that of being an Indian, was told in

Ixcanul

, "in a country where more than 60% of the population is indigenous, and that is clear on the street."

The filmmaker puts as proof of this fear of ethnic discrimination the last census of his country, "where only 41% of the population called themselves indigenous."

He defined himself as a Ladino, "a word that also carries a terrible past";

he prefers the term mestizo.

"And so I told the census takers, who three weeks later told me it was not worth a pejorative, something ridiculous."

The second contempt stems from homophobia, and is illustrated in

Tremors

.

"For me, homophobia is directly linked to machismo," says Bustamante.

“Since the Mayans, my country has not changed in its pyramidal conception: above, religion, force.

Below, the rest ”.

For this reason, in Tremors the protagonist, an upper-class executive married with children who one day makes his homosexuality public, belongs to a fundamentalist evangelist church.

"It is the creed that has triumphed in Guatemala since the eighties with the dictatorship of General Ríos," and he sighs after a half smile.

“The worst thing is that women, the most abused, have become the guardians of religion.

Fear of change, of breaths of fresh air?

And so comes the third insult: "Communist."

Although the filmmaker explains: “Comunista does not have a political meaning in Guatemala, but rather names anyone who cares about human rights.

Do you want justice to be applied?

Communist.

Do you want impunity to end?

Communist.

Do you support progress?

Communist.

Thus we have ended up being leaders of America in discrimination, chronic malnutrition and illiteracy ”.

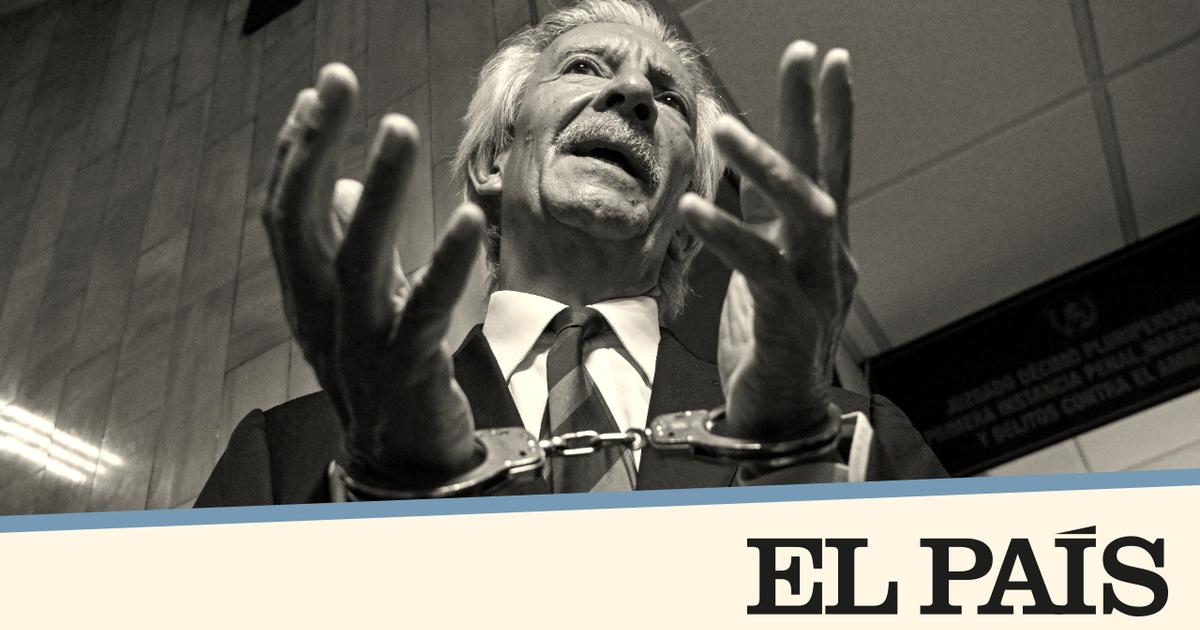

Hence,

La Llorona was

born

,

in reference to the mythical song, a horror film in which the ghosts of the victims assault the dreams of a dictator and his family.

"Going out to the streets today for my country is an act of courage."

With all of the above, Bustamante feels very pessimistic: “There is a lost generation that will not change.

Mine still talks about certain things, but we inherit fear and those insults.

Only today's teenagers can lead a change ”, although with a risky bet.

"Everything depends on education, and that is in the hands ...".

A gesture of pain finishes the sentence.

The filmmaker shoots with "little money, behind the back of the system, doing tricks to make it appear more productive."

If in

Tremors

there are great camera shots, in

La Llorona it

had a cameo by the Nobel Prize winner Rigoberta Menchú, "which adds truth to the film."

In

La llorona,

Bustamante turns away from drama to terror.

“Being, as we are, a Caribbean society, colored thanks to the Mayan past, we are surrounded by an obscurantism rooted in what we do not want to talk about, in looking away.

I am outraged by these new movements of positivism -a terrible word-, which say that you smile so that the country goes better.

That's silly.

It makes you irresponsible for the past, it doesn't go with you, it makes you close your eyes ... And that's

La Llorona, ”he

explains, underlining that moment when the Guatemalan Supreme Court is the one who closes his eyes.

“We only have magical realism left to respond to impunity.

That weeping woman is Mother Earth crying for her disappeared in massacres ”.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/MWIKHA6MKFGSTFNPVMTJJSIZDU.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/EWJ6D24N4FAMNMM5L7QDF7NQFM.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/TSUEZ7K7S5HNDE7GY53532ZZ7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/34ZR4HH37ALPAI5BSQHC3V42QE.jpg)