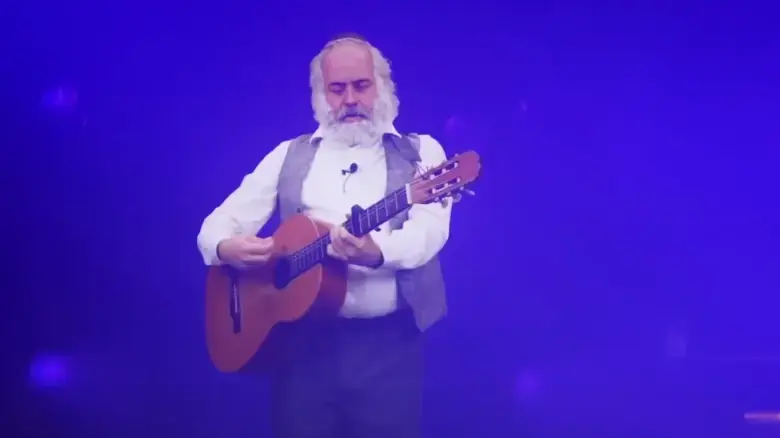

The Chilean group Las Tesis during a performance in Buenos Aires, on February 19.

/ Europa Press

In 2005, Chilean Minister Víctor Montiglio investigated an operation by the National Intelligence Directorate (DINA) that covered up the forced disappearance of opponents of the military dictatorship.

He questioned the dictator Augusto Pinochet about his implications in this operation, one of many that took place in the 17 years of the regime (1973-1990).

From that historic questionnaire, almost all the answers that Pinochet answered were left for posterity: "I don't remember" and "It's not true."

A year later, the group Los Tres turned the statements into the chorus of their song It's

Not True

, from the band's sixth album entitled

Do it yourself

, whose lyrics, quoting the words exactly as the general said them, read like this: “God will forgive if I went too far, but I don't believe.

All the trouble I caused I dedicate to heaven.

I do not remember, but it is not true and if it is true I do not remember.

The recent history of Chile cannot be told without the social movements that emerged from the coup in 1973, and the music that these originated.

Los Tres are part of a long list of groups and artists from different generations who have used all musical genres to show part of the reality they live.

And neither can Chilean history be told or sung without mentioning Violeta Parra and Víctor Jara, who with their songs prior to 1973 set a precedent for all that music that emerged first timidly and then as an explosion after the dictatorship.

For the Chilean journalist Manuel Maira, specialized in music and author of three titles on the subject, before the dictatorship Chile had formed a movement in music with a powerful social discourse, led by Jara, Parra or the Quilapayún group.

But he identifies a void in later years.

"With the coup there was a hard cut of all that and a huge cultural blackout," he says.

Javiera Tapia, music journalist and founder of the esmifiestamag.com site, of journalism and feminism, agrees.

According to her, "those songs are in the memory of the people as a political song and have been transformed into hymns, the people have transformed them into that."

Maira, author of one of the biographies on Jorge González, the vocalist and leader of Los Prisioneros, relates that after the dictatorship the opportunities for artists to say “more things” were opened as promises: “From

Los Prisioneros soon appeared, with the figure of Jorge González, a middle-class type who was very different from the Chilean prototype, a frontal type that bothered him, who asked him something and said exactly what he thought.

In those years we were already closer to achieving democracy ”, he says.

In 1986, Los Prisioneros released a song that is, until now, one of those hymns that continue to be sung not only in Chile but also in latitudes as distant and at the same time as similar as Colombia, Mexico or Peru.

The dance of those who are left

, written by Jorge González, has once again been a symbol in the demonstrations that refuse to die even now, 34 years after being written, and almost a year of what Chileans call "the social outbreak." October 2019. When the increase in the subway rate unleashed discontent accumulated for decades and led to the most violent and massive demonstrations since the return to democracy in 1990 (”

Join the dance, the ones that are left over. to miss more. Nobody really wanted to help us "

).

The Chilean popular music journalist and researcher Marisol García identifies that the Chilean song has been undeniably marked by the awareness of the conflicts around those who create music, and in the complaints they are willing to make through popular poetry, deeply rooted in the countryside and cities.

Garcia says: “Chile has high quality in its social song, just as other countries have it in musical genres associated with the romantic, dance or fusion.

It cannot be a coincidence that in less than three decades we have Violeta Parra, Víctor Jara, Patricio Manns, Jorge González and so many other names of international attention ”.

The new generations of musicians continue to claim the musical heritage of their predecessors.

In 2011, the great year of the student explosion in Chile, the song

Shock

, by the composer and rapper Ana Tijoux, flooded the streets of the entire country along with those massive protests.

The demand was the defense of public and free education, with a combative lyrics and a video recorded in the most turbulent days of the mobilizations in Santiago, the song also portrayed the millennial protest of the Mapuches, the indigenous people settled in the south of Chile, who demanded respect for their territory and their dignity.

Other important names in social demand through songs have been musicians as young as the

trap

singer

Pablo Chill-E, 19, with his 2018 song

Facts

, a critique of power in Chile;

or the danceable but impressive

No

, by the composer and producer Nicolas Jaar, who relives with an electronic background the feelings of Chilean society that, although it had voted "No" to the continuation of the Pinochet military dictatorship in 1989, lived immersed in a reality militarized and full of fear: “

We already said no.

But the yes is in everything.

The inside and the outside.

From far and near ... ”.

Yorka, the duo of the Yorka sisters and Daniela Pastenes, aged 29 and 25, is also an example of how all this musical tradition comes together.

In 2019, after the social outbreak, they wrote

The song is protest

, from their third album

Humo

.

It is a work that reflects the historical moment of Chile, but also its personal and professional evolution.

“I think that Chilean music was born contingent.

I feel that our first songs already speak of inequality ”, says Yorka Pastenes.

Both sisters, who are also music teachers and who were born and carry out all their activity in San Bernardo, on the outskirts of Santiago, the capital, assure that before Violeta Parra, Chilean music did not have an identity.

“These leading artists for us did not have happy endings.

And none of those artists lived the success that they had.

I think Violeta died without knowing what it was and that terrifies me.

And I think Victor Jara ... I can't even imagine what he was going through tortured by this shitty country.

Chile is a country that was born from death and genocide.

I wish we could sing about other things ”.

'A rapist on your way', the feminist revolution from Chile

And if there is something that could already be considered an anthem of this latest Chilean revolt, not only because of the social outbreak and discontent but also because of the unprecedented appearance of the female figure and its demands, it is 'A rapist on your way', by the collective Las thesis, the public representation of women who speak about gender violence, and which has sounded beyond Chile and even the combative Latin America.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/C2MIK5VAZ5CB7DSENNGRRAOSRM.jpg)