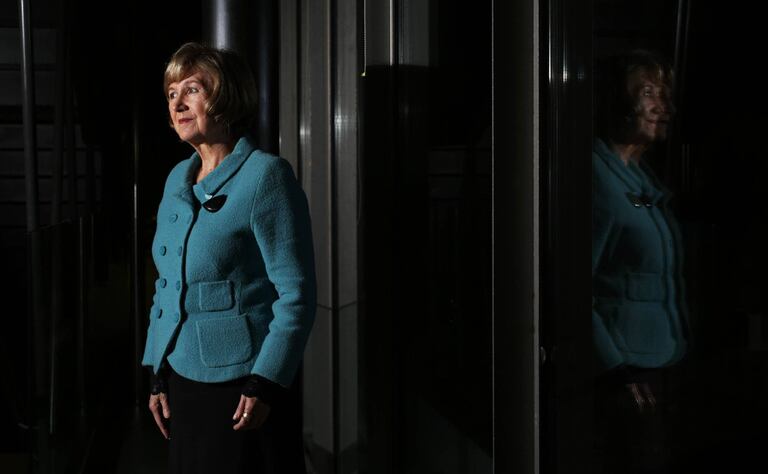

The writer Lídia Jorge, photographed in 2017 in Madrid.ÁLVARO GARCÍA

Lídia Jorge (Boliqueime, 74 years old) has known all the ages of misfortune, in Portugal, in Europe and in the world, because the 20th century gave her the sad opportunity to have before her the traces of dictatorship, violence and wars .

For recounting those episodes that mark his literature, he has just won the prize at the Guadalajara International Book Fair (Mexico) almost at the same time that his novel

Estuario

(La Umbría y La Solana, translated by María Jesús Fernández)

is published in Spain

.

It is the chronicle of the ruin of a Portuguese shipowner;

its moral and political consequences turn this family fiction into a story that appeals to other ruins of the 20th century and this 21st century, which has started with a universal episode of long-lasting pain.

She is the author of

The Coast of Murmurs

,

The day of prodigies

and

The times of splendor

(this in the aforementioned publisher), among other works.

The conversation with her was made by phone.

Question.

Estuary

refers to the consequences of ruin, also moral ruin, which you turn into a metaphor.

Answer.

We are living moments that escape us and that start in 2008, when the financial and economic system rotted.

From that moment on we had to face the idea that we were going to the abyss.

I had a hard time understanding how ordinary people would manage to cope with this ruin, and I think culture has some answers.

This book is the initiation of a young man who wants to save the world, but understands that this is not possible if each one does not save the people closest to him.

The book is about that melancholic ruin that we do not see as a war, but that we perceive as a structure that is shaking.

It is like a slow earthquake, although around Europe there are other earthquakes that are not slow, they are very serious and precise, such as those that occur in the Middle East.

The people who come and are cornered in concentration camps are the image of the European abyss

Q.

And between us?

R.

The people who come and are cornered in concentration camps are the image of the European abyss.

As a whole, it is a threat that is creating a social and individual ontological earthquake.

My book is, therefore, a reflection on a time that anticipated what was going to happen.

It has exploded in the wild, but it was brewing in the global public space.

Q.

In

Estuary

this is represented as in that metaphor of

The Stranger,

by Camus: the world was knocking at the door of misfortune ...

A.

Exactly.

The idea of wanting to save the world is already an impossible utopia.

Each one has to save the neighbor when the earthquake begins to be serious.

This idea of

The stranger

who does not understand what is happening is very important, as is the Gramscian theory that it is not a sensitivity for the collective, but rather abstract, that leads you to feel sorry for yourself, to share the joy or displeasure of those who are close.

When you stop being a foreigner, you can be it in the face of the utopias that lie ahead.

Q.

Those wounds from the dictatorship, from the wars, which affected Portugal like us, do they help you to interpret today's world?

R.

I feel very close to Portugal, a country that in the second part of the 20th century had a more deeply rooted medieval structure than that of Spain.

We got into a colonial war when we were a poor country that was reaching out for international alms, and yet in our imaginary we had the idea that we were the head of a magnificent, grand empire.

This dystopia has led us to 14 years of stupid war, completely anachronistic, without dialogue with others, without a historical sense of the temporality that we lived.

Portugal has gone through times of great anguish and uncertainty.

We got into a colonial war when we were a poor little country that reached out for an international handout

P.

But they came out of there making the revolution.

A.

Yes and with all the consequences of the change.

It was very difficult for Portugal because we went from a very backward situation to one in which, to a certain extent, we became modern.

This is not done without great pain.

I have felt all that change, that always dramatic fold.

We have suffered tremendous waves and that has opened the understanding of the Portuguese for the suffering of Europe, and especially for the pain of peripheral countries.

We understand what is happening in the Middle East because we have been immigrants and poor and we have had a difficult diaspora.

Q.

That is the subject of your writing too ...

A.

As writers we observe this furious time that we are living in fear of going back.

The Portuguese have not lost their fear of poverty, they feel it.

Curzio Malaparte says: “The poor don't make big changes;

first they have to have eaten what is necessary to have a revolutionary attitude ”.

And it is true: the Portuguese are still afraid of going back to poverty, to war.

We have a memory that enables us to understand what is happening in Europe and all the changes that are perceived in the world.

Those of our generation are older, but we have a vision of the past that we also project forward and that is why we maintain that fear that something very serious will happen even in our time.

I like young people who have breasts, but have no back, who see life with hope.

We have hope, maybe joy, but memory, that is, our back, tells us to be careful.

In Spain everything is more visible.

You have the advantage that everything is done publicly.

Here is more hidden

Q.

That past has had consequences in current Portuguese literature.

A.

Yes, we keep talking about it ... It was the great trauma caused by an unjust war in which at the same time the idea that we had brothers far away became solid, and that is an essential part of our identity.

Many well-known writers have written about it, and now

Bahía de los Tigres,

by Pedro Rosa Mendes,

has appeared

, an absolutely precious book in which he writes about what Portuguese culture left behind in African countries and the minorities of our supposed fraternity .

There are especially women who are writing very well about the feeling of people's return.

Q.

Does politics continue to damage that memory or has it got rid of history?

R.

The political terrain is difficult because Portugal maintained the same colonial structure as here, of stratified peoples;

those who could have had culture had it, those who were in jail did not.

We did not have universities there, the schools were very racist, the educational and cultural system had a very broad base ... The human mix was wonderful, but the Portugal of politics has not echoed it.

There are now four or five parliamentarians in Parliament who have the mark of Africa on their skin, but in general they have very little representation.

And people demand a repair.

To this is added the activity of a very powerful extreme right, represented by Chega, a kind of Portuguese Vox, which in its program includes doing evil to a black man, a homosexual or a woman.

He has just proposed that women who have an abortion have their womb pulled out, and Nazis join their ranks ... It is terrible: suddenly we are in a different situation than the one we lived in all the years of peace.

Q.

We are neighbors and we have parallel lives.

A.

Yes, but in Spain everything is more visible.

You have the advantage that everything is done publicly.

Here it is more hidden, it is darker and we delimit it very well.