The concept of "intellectuals" is quite curious.

Who can we consider as such?

Here is a question that was approached in a very instructive way in a classic essay that Dwight Macdonald wrote in 1945, entitled

The Responsibility of the Intellectuals.

That text is a sarcastic and relentless criticism of those distinguished thinkers who pontificated on the "collective guilt" of German refugees as they barely survived amid the catastrophic ruins of war.

Macdonald there compared the Pharisaic contempt that such distinguished feathers showed towards the unfortunate survivors with the reaction of many soldiers of the victorious army, who, recognizing the humanity of the victims, sympathized with their suffering.

And yet the first are the intellectuals, not the second.

Macdonald concluded his essay with a few simple words: "How wonderful is the ability to see what is right in front of you."

What, then, is the responsibility of the intellectuals?

Those who fall into that category enjoy that relative degree of privilege that such a position confers on them, which offers them opportunities that are superior to normal.

Opportunities come with responsibility, which, in turn, involves having to decide between alternative options, something that can sometimes be very difficult.

Thus, one possible option is to follow the path of integrity, wherever it leads.

Another is to put aside those concerns and passively adopt the conventions instituted by authority structures.

The task, in this second case, is limited to faithfully following the instructions of those who hold the reins of power, to be loyal and faithful servants, not as a result of a reflective judgment, but by a reflex response of conformity.

This is a very subtle way to avoid the moral and intellectual complexities inherent in a questioning attitude, and to avoid the potentially painful consequences of striving to curl the vault of the moral sky toward the cause of justice.

We are familiar with those kinds of alternatives.

That is why we distinguish the commissioners and

apparátchiki

from the dissidents who take up this challenge and face the consequences (consequences that vary depending on the nature of the society in question).

Many dissidents achieve fame and deserved recognition, and the harsh treatment they receive or received is duly denounced with fervor and indignation: there are Václav Havel, Ai Weiwei, Shirin Ebadi and other figures that make up a long and distinguished list.

It is also fair that we condemn apologists for bad society, those who do not go from the occasional lukewarm criticism to the "errors" of rulers whose intentions are globally and systematically described as benign.

There are other names, however, that are missing from the list of recognized dissidents: for example, those of the six prominent Latin American intellectuals, Jesuit priests, who were brutally assassinated by Salvadoran forces who had just received military training from the US Army. and they acted following specific orders from their government, a satellite of the United States.

In fact, they are hardly remembered.

Very few even know what they were called or keep the slightest memory of those events.

The official orders to assassinate them have not yet appeared in any of the major media in the United States, and not because they were secret: they were published with full visibility in the main newspapers of the Spanish press, for example.

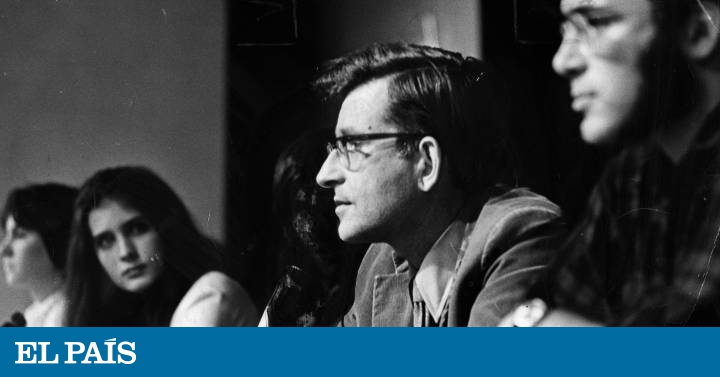

Chomsky, speaking at a rally in defense of the rebels of the Vietnam War in New York in 1968. US National Archives

I am not talking about something exceptional.

Rather, it is the norm.

Those facts are not inextricable at all.

They are well known to activists who have protested against the heinous crimes promoted by the United States in Central America, and also to experts who have studied the subject.

In one of the entries in

The Cambridge History of the Cold War,

John Coatsworth writes that, from 1960 until “the Soviet fall in 1990, the numbers of political prisoners, victims of torture and non-violent political dissidents executed in Latin America exceeded by far those registered in the Soviet Union and its Eastern European satellites ”.

However, the same panorama is drawn precisely in reverse as it appears treated in the media and in the magazines of intellectuals.

To take just one striking example of the many possible, I will say that Edward Herman and I compared

The New York Times'

coverage

of the murder of a Polish priest - whose murderers were promptly located and punished - with that of the murders of a hundred religious martyrs in El Salvador –including Archbishop Óscar Romero and four American nuns–, whose perpetrators remained hidden from justice for a long time while the United States authorities denied the crimes and the victims received nothing from their government except official contempt.

The news coverage of the case of the priest assassinated in an enemy state was vastly broader than that dispensed to the hundred religious martyrs assassinated in a satellite state of the United States, and its style was also radically different, very much in tune with the predictions of the so-called “ propaganda model ”to explain how the media works.

And this is only one illustration among many possible ones of what has been a constant pattern over many years.

Mere servitude to power may not explain everything, of course.

On occasions - very rare - the facts are recorded, although accompanied by an effort to justify them.

In the case of religious martyrs, the distinguished American journalist Nicholas Lemann, national correspondent for

The Atlantic Monthly, a

magazine with a “liberal” (center-left) editorial line, provided an alternative explanation in a supposedly sarcastic response to our work: The discrepancy can be explained by saying that the press tends to focus on only a few things at any given time, "wrote Lemann, and" the American press was then mostly focused on Poland. "

Lemann's thesis is easy to contrast by examining the

New York Times

index

, where it can be seen that the duration of the news coverage provided to the two countries was practically identical in both cases, and even a little longer in El Salvador. .

But, of course, in an intellectual context where "alternative facts" have a place, details like that seem to matter little.

In practice, the honorific term “dissident” is reserved for those who are dissident in enemy states.

The six murdered Latin American intellectuals, the archbishop and the many others who, like them, protest against state crimes in satellite countries of the United States and are murdered, tortured or imprisoned for it, are not called "dissidents" (if it is that are even mentioned).

Noam Chomsky, teaching a class at the Free School University, an initiative of the Occupy Boston collective, in October 2011. Matthew J Lee / The Boston Globe Getty

There are also terminological differences within the country itself.

There were, for example, intellectuals who protested the Vietnam War for various reasons.

To cite a couple of prominent examples illustrating how narrow the elite's spectrum of vision is, journalist Joseph Alsop once complained that US intervention was being too contained, while Arthur Schlesinger replied that escalation is probably not. it would work and it would end up being too expensive for us.

However, he added, "we all pray" that Alsop is right in considering that US strength may prevail, and if it does, "then we may all recognize the prudence and sense of state of the US government" to achieve victory, even at the cost of leaving that "unfortunate country destroyed and devastated by bombs, calcined by napalm, turned into a wasteland by chemical defoliants, reduced to ruins and rubble", and with a "political and institutional fabric ”Reduced to ashes.

And yet Alsop and Schlesinger are not called "dissidents."

Rather, they are seen as a "hawk" and a "dove," respectively - two figures that mark opposite ends of the spectrum of what is understood to be legitimate criticism of America's wars.

Of course, there are also voices that fall off the spectrum entirely, but those are not considered "dissidents" either.

McGeorge Bundy, Kennedy and Johnson's National Security Advisor, said in an article for

Foreign Affairs,

an

establishment

magazine

,

that they were "behind-the-scenes savages" who oppose American aggression on principle, regardless of the issues. tactics about its feasibility and cost.

Bundy wrote those words in 1967, at a time when the relentlessly anti-communist military historian and Vietnam specialist Bernard Fall, well respected by the US government and mainstream circles of opinion, feared that “Vietnam as a cultural and historical entity […] is in danger of extinction […] [now that] the countryside is literally dying under the impacts of the largest military machine ever deployed against a territory of that size ”.

But only the "savages behind the scenes" had the nerve to question the justice of the American cause.

At the end of the war in 1975, intellectuals from across the spectrum of dominant opinion gave their interpretations of what happened.

They covered all fringes of the Alsop-Schlesinger spectrum.

From the end of the "doves", Anthony Lewis wrote that the intervention began with a series of "clumsy well-intentioned efforts" ("clumsy" because they failed, and "well-intentioned" by doctrinal principle, without the need for proof), but by 1969 already it was obvious that the intervention was a mistake because the United States "could not impose a solution except at a price that was too expensive for itself."

At the same time, polls showed that around 70% of the population did not consider the war to be “a mistake”, but “inherently unjust and immoral”.

But of course, like those soldiers in 1945 who empathized with the suffering of unfortunate German refugees, the respondents are not intellectuals.

Examples are typical.

Opposition to the war reached its peak in 1970, after the invasion of Cambodia orchestrated by the Nixon-Kissinger duo.

Just then, the political scientist Charles Kadushin conducted an extensive study of the attitudes of "elite intellectuals."

And he discovered that, regarding Vietnam, they adopted a "pragmatic" stance of criticism of the war, considering it a mistake that ended up being too expensive.

The “backstage savages” didn't even count, lost in the statistical margin of error.

Washington's wars in Indochina were the worst crime of the post-World War II era.

The worst crime of the current millennium is the British-American invasion of Iraq, with dire consequences throughout the region that are still far from reaching an end.

The intellectual elite have also been at their customary height this time.

Barack was highly praised by center-left liberal intellectuals for taking a stand with the "doves."

In the words of the president, “during the last decade, American troops have made extraordinary sacrifices to give Iraqis the opportunity to claim their future for themselves,” but “the harsh reality is that we have not yet seen the end of the American sacrifice. in Iraq ”.

The war was a "serious mistake", a "strategic blunder" at a cost more than excessive for us, an assessment that could well be equated with the one that many Russian generals made in their day about the Soviet decision to intervene in Afghanistan.

This is a generalized pattern.

It is not necessary to cite any example, as there are plenty of published studies on the matter, although these do not seem to have had the least effect on the doctrine of the intellectual elite.

From the frontiers to the inside, there are no dissidents, neither commissioners nor

apparátchiki.

Just backstage savages, on the one hand, and responsible intellectuals - those considered the true experts - on the other.

The responsibility of the experts has been detailed by one of the most eminent and distinguished of them all.

Someone is an "expert", according to Henry Kissinger, when he "elaborates and defines" the consensus of his public "at a high level" (understanding as "public" those people who establish the frame of reference within which the experts execute the tasks entrusted to them).

The categories are fairly conventional and date back to the earliest use of the concept of "intellectual" in its contemporary sense, during the controversy of the Dreyfus affair in France.

The most prominent figure of the

Dreyfusards

,

Émile Zola, was sentenced to a year in prison for having committed the infamy of calling for justice for the falsely accused Alfred Dreyfus, and fled to England to avoid further punishment.

He was then harshly disapproved by the "immortals" of the French Academy.

The

Dreyfusards

were true "backstage savages."

They were guilty of "one of the most ridiculous eccentricities of our time", to put it in the words of the academic Ferdinand Brunetière: "the pretense of raising writers, scientists, professors and philologists to the category of supermen" who dare to "treat from idiots to our generals, from absurd to our social institutions, and from insane to our traditions ”.

They dared to meddle in matters that should be left to the "experts", "responsible men", "technocratic and politically pragmatic intellectuals", according to the contemporary terminology of the liberal center-left discourse.

Well, what, then, is the responsibility of the intellectuals?

They can always choose.

In enemy states, they can choose to be commissioners or to be dissidents.

In the satellite states of American foreign policy, in the modern period, that choice can have indescribably tragic consequences for these people.

In our own country, they can choose between being responsible experts or being wild behind the scenes.

But there is always the option of following Macdonald's good advice: "How wonderful is the ability to see what is right in front of you," and simply have the honesty to tell it as it is.

'The responsibility of the intellectuals'

Author: Noam Chomsky

Translator: Albino Santos Mosquera

Publisher: Sixth Floor

Format: Rustic.

132 pages

Find it in your bookstore