Who else, who less, knows what an ultra-processed product is: I know it, you know it and the manufacturers do too.

But, regardless of whether or not there is an institutional and consensual definition of the matter, - the truth is that there is none - no one transfers any healthy characteristics to this range of products.

To date, the food industry that makes the worst nutritional profile products has faced its demons with sportiness and as they came to it.

We could even say that he has faced them with delight, since in the face of difficulties and problems he has seen opportunities, and far from backing down or being daunted, he has taken advantage of them.

But the term ultra-processed is a brown beast that it intuits, or rather knows, that it has nothing to do.

Therefore, the current strategy of large food corporations on the international scene consists of discrediting the term and, if necessary, judicializing its use based on complaints against those media, administrations or even individuals that use it.

Does it seem exaggerated?

A recent report from the Triptolemos foundation on the term in question proposes, verbatim, the following:

“From a legal perspective, the use of the term or concept 'ultra-processed' by political or administrative authorities could be punishable.

[...] Nor can it be excluded that those companies whose products are denigrated with this qualifier among potential buyers, may appeal to the judicial bodies to compensate for the damages caused.

Do not forget the links of this Foundation with a certain food industry -you just have to see who its members are-, affiliation and interests that surely explain the large number of gaps -both legal and editorial- that there are in that single paragraph (I highly recommend the Legal assessment made of this report by the lawyer and author of the book

The Law in Nutrition,

Francisco Ojuelos, where he reveals the report in question).

But why does this word scare you so much?

The war of the ultra-processed is impossible to win for the industry

There was a time when the more industrial food

industry

- worth the redundancy - was venerated almost as a divinity.

The era of fat cows had its origin - more or less and with its ups and downs - thanks to two coinciding events at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th.

Undoubtedly the first, the industrial revolution, which together with the development of various means of preservation and production, provided the possibility of putting large quantities - industrial? - of safe food on the market;

all without the need to try as hard as before.

The second, the advent of nutritionism, which in a few words consists of going from worrying about whether or not you will be able to eat, to obsessing over the vitamin or other nutrient content of what you eat.

For example, stop worrying about knowing if you are going to have milk to drink and focus on having it skimmed or - even more squeaky - considering a piece of industrial pastry for good because it is enriched in iron.

The first preserves, powdered milk -not to mention the first infant formulas-, foods fortified with dozens of vitamins and minerals and a very long etcetera, in their time delighted a population whose main concern was malnutrition and incidence of deficiency diseases due to lack of vitamins and minerals.

But that bonanza was not going to last forever.

The first big deal for the industry came, more or less, towards the 1950s of the last century, when the incidence of deficiency diseases stopped but those known as non-communicable diseases began to be visible.

The first to come to the fore was cardiovascular disease, followed by diabetes and cancer ... and what to say about overweight and obesity.

It was then that the role of that more

industrial

food offer began to be highlighted

, which, far from curing, could at the same time be the cause of disease.

The first horseman of the apocalypse for the industrial products sector was identified in the form of calories, the second in the form of fat and the penultimate in the form of sugar.

But what in the first instance could seem negative for the sector became an opportunity, and along with the old offer appeared the products low in calories or

light

, low in fat or without it, and the same for sugar.

This is what is called line extension or extension and it usually implies almost always a benefit for the sector: the problems, although it seems a contradiction, have always been good for the industry, because it has always had a commercial response.

Until now.

How can you remove the stigma of being ultra-processed from surimi sticks?

And to some cookies, a corn snack extruded until the bars of salt and Tex-Mex flavor or a strawberry yogurt without strawberry?

I'll tell you: putting bream or sardines, apples, nuts and natural yogurts respectively.

That is to say, eating real food: for the moment, for this war, the industry has no answer, since the term ultra-processed makes it difficult - when it does not prevent - the adored and dangerous reformulation by the industry.

If you fall for that sanmbenito, you cannot take advantage of it, that is why the sector charges against the term, while undervaluing the criteria of the concept and discrediting its use.

Despite this, and in addition to the aforementioned studies, both the WHO and the FAO itself make extensive use of the term ultra-processed directed to food products: in the linked documents you can read the terrible consideration that these institutions have of them.

We don't know what Nutri-score says, but they are bad.

UNSPLASH.COM

Is it 'ultra-processed' to classify unhealthy foods?

In 2009, a team of researchers led by Carlos Monteiro published a classification of foods that took into account -although not exclusively- their degree of processing.

His idea was to find a common denominator for all those food products that had a clearly unhealthy or undesirable profile.

That is to say, a pattern was sought that would characterize what is known as junk or junk food.

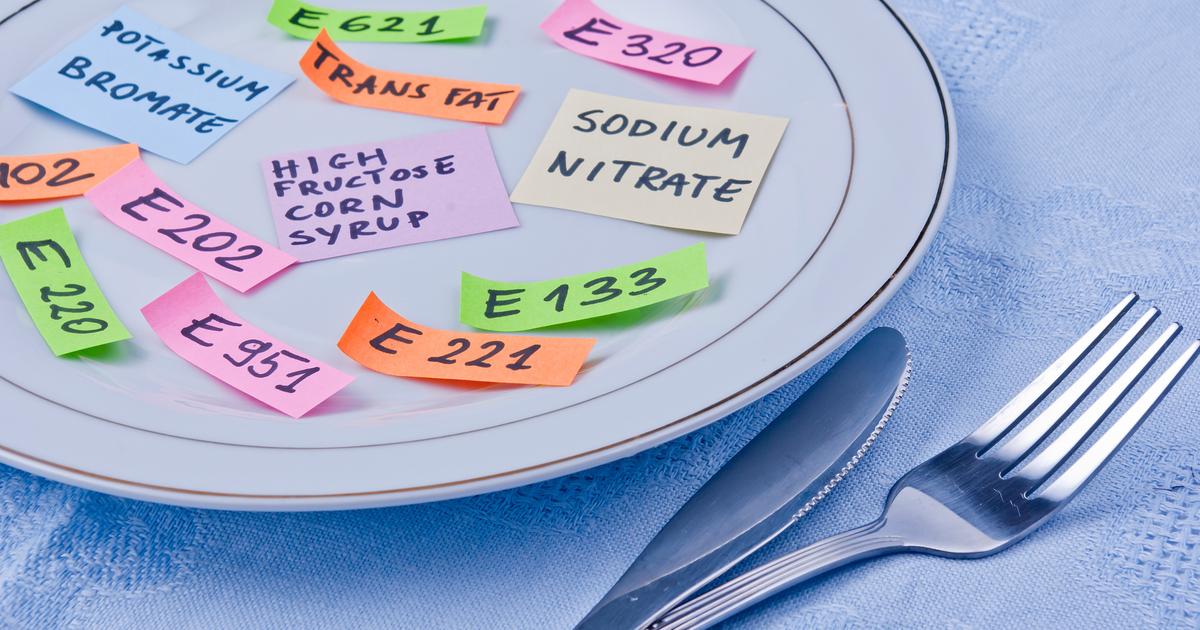

I am referring to those products that have been distinguished by the conjunction of some of these characteristics: having a significant caloric density -or being low or without calories, but at the same time providing little or no nutritional value- being high in sugar, salt or sodium, total fat, or saturated fat;

especially trans fats, and at the same time, being poor in vitamins, minerals, fiber and essential fatty acids.

This was the case with the NOVA system - described in this article - which was the first system to use the term 'ultra-processed'.

Its precision is quite striking when it comes to identifying nutritional waste (unlike the widely embraced -by the industry- Nutriscore).

True, it uses an unorthodox procedure, but it works;

just the opposite of what happens to Nutriscore, with a supposedly rigorous theoretical framework -not so much if we take into account the ugly olive oil issue- but when it is put into practice, it has more holes than the

Titanic

script

2

.

Some time ago we commented on some of the scientific publications that have revealed the relationship between the consumption of ultra-processed products with a worse general nutritional profile and with a -much- worse health prognosis in relation to diseases such as diabetes, cancer or cardiovascular diseases;

as well as weight gain and, in general, mortality.

And there is much more research that associates this term, in most cases, with worse intermediate markers and worse dietary and health indicators.

The strategy against the term

For about three years there has been a stream of scientific publications aimed at discrediting the term "ultra-processed".

One of the most determined authors is the researcher Michael Gibney, from the University of Dublin.

Throughout his career, he has received funding from Nestlé, Mondelez, PepsiCo, Unilever, Nestlé and Coca-Cola, among others, even at the time of writing his papers.

In one of the best known,

Ultra-processed foods in human health: a critical appraisal

, the father of the term ultra-processed, Carlos Monteiro, maintains that in addition to Gibney, two other authors concealed their conflicts of interest with Nestlé and McDonalds.

Pulling the thread, it can be contrasted that the prestigious magazine where it is published, the

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

, is, since 1952, one of the dissemination organs of the American Society for Nutrition, an entity that has quite special sponsoring partners .

Among them: the National Distilled Beverages Council of the United States, General Mills, Herbalife, Kellogg, Mars, Pepsi, Nestlé, Mondelez, the American Sugar Association and Unilever.

In Spain we have witnessed the publication of three scientific writings in just two months, positioning ourselves against the use of the term ultra-processed.

The first was the one that appeared in No. 31 of the magazine of the Scientific Committee of AESAN, entitled

Report of the Scientific Committee of the (AESAN) on the impact of the consumption of 'ultra-processed' foods on the health of consumers

.

I do not know if it is a coincidence -but it certainly does not seem so- that this report precedes another focused on the opinion of the Scientific Committee itself regarding the validity of the Nutri-score, the front labeling system that the industry is openly betting on in this moment.

The summary of both reports: cheers for the Nutri-score, and thumbs down for the ultra-processed term.

Both reports present, in my opinion, various shadow areas and even inaccuracies that, obviously, facilitate institutional discourse.

They are baked, but just as dodgy.

UNSPLASH.COM

In June, two of the authors who have fought the most for the defense and institutional implementation of Nutriscore in Spain published

Ultraprocessed Foods.

Critical review, limitations of the concept and possible use in public health

.

In this review, written as part of a contract between Danone SA and the Fundación Institut d'Investigació Sanitària Pere Virgili, SA - Danone is one of the most fervent defenders of Nutriscore and has financed various works by the authors of the review - it is said that the term ultra-processed is reductionist, manipulable under subjective criteria and there is not enough evidence to justify its use.

In return, the use of Nutriscore is proposed, a system to which an exclusive section is dedicated (surprise!).

Although it is possible that they prohibit us from using the term ultra-processed -and until they denounce us if we do-, we can always act like Galileo Galilei when he had to renounce his heliocentric proposal before the Holy Inquisition, and give our version of his “

Eppur yes moove

”.

In this case it would be "and yet it makes you sick."

Juan Revenga is a dietician-nutritionist, biologist, consultant, professor at Universidad San Jorge, member of the Spanish Foundation of Dietitians-Nutritionists (FEDN) and a lot of other brainy things that you can read here. He has written the books “With hands on the table. A review of the growing cases of food infoxication ”and“ Make me slim, lie to me. The whole truth about the history of obesity and the weight loss industry ”and - very importantly - he is a fan of his mother's sherry kidneys.

His (supposed) weak point is his lack of concreteness

All those organizations, foundations, etc. - in addition to the ultra-processed industry - that bet on putting the term within a poster of "wanted dead or alive", appeal to the same thing: the lack of consensus in its definition.

We are going step by step, because the subject is not simple.

It is true: there is no agreed definition to which we can go to find out what an "ultra-processed product" is.

In fact, in our legislation, the definition of “processed product” does not even appear: the closest thing to this terminology is that of “transformed product”.

A term that comes from the English translation of European Regulation (EC) No. 852/2004.

Curiously, what is referred to in the Spanish text as "transformed product" in the original text is called "processed product".

It seems that there is a tacit agreement, when it comes to equating the two terms -transformed and processed- in scope and scope, as if they were synonymous.

In this sense, the terms transformed and processed have long been used by a specific sector: the one most closely involved with food production.

To put a face and eyes on it, let's say it is the professional sector that brings together people specialized in food science and technology.

In this environment, a transformed or processed product has always made reference to the technology that is applied at a given time to a certain food, in order to evaluate its effect on food and nutritional safety issues (such as the loss of certain nutrients or changes in the bioavailability of others).

If we appeal to the Dictionary of the Royal Academy of the Language, the application of the prefix 'ultra' to the words 'processed' or 'transformed' should mean that the corresponding technological operations are applied to an extreme degree.

However, the new application (2009) of the term "ultra-processed food" goes further and is used -both in scientific and popular terms- to transfer clearly negative nutritional characteristics to products that are called this way due to their impact on health.

If the adjective processed -or transformed- has been used in relation to the application of a series of technological processes, the term "ultra-processed" also implies that the consumption of these products is little or not recommended for health.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/4JS5XE5N7BE6NOR4VBBTTDLQU4.JPG)