European and American scientists say they have found possible signs of life on Venus, the planet closest to Earth.

This world is an old acquaintance of earthlings that, however, we have not visited for decades, because we had no hope of finding anything alive there.

The finding is still preliminary and needs to be confirmed, but its authors say that one of the most plausible explanations for their observations is that there is life on this planet.

Many of the independent experts consulted by this newspaper answer that the evidence is not enough to draw that conclusion.

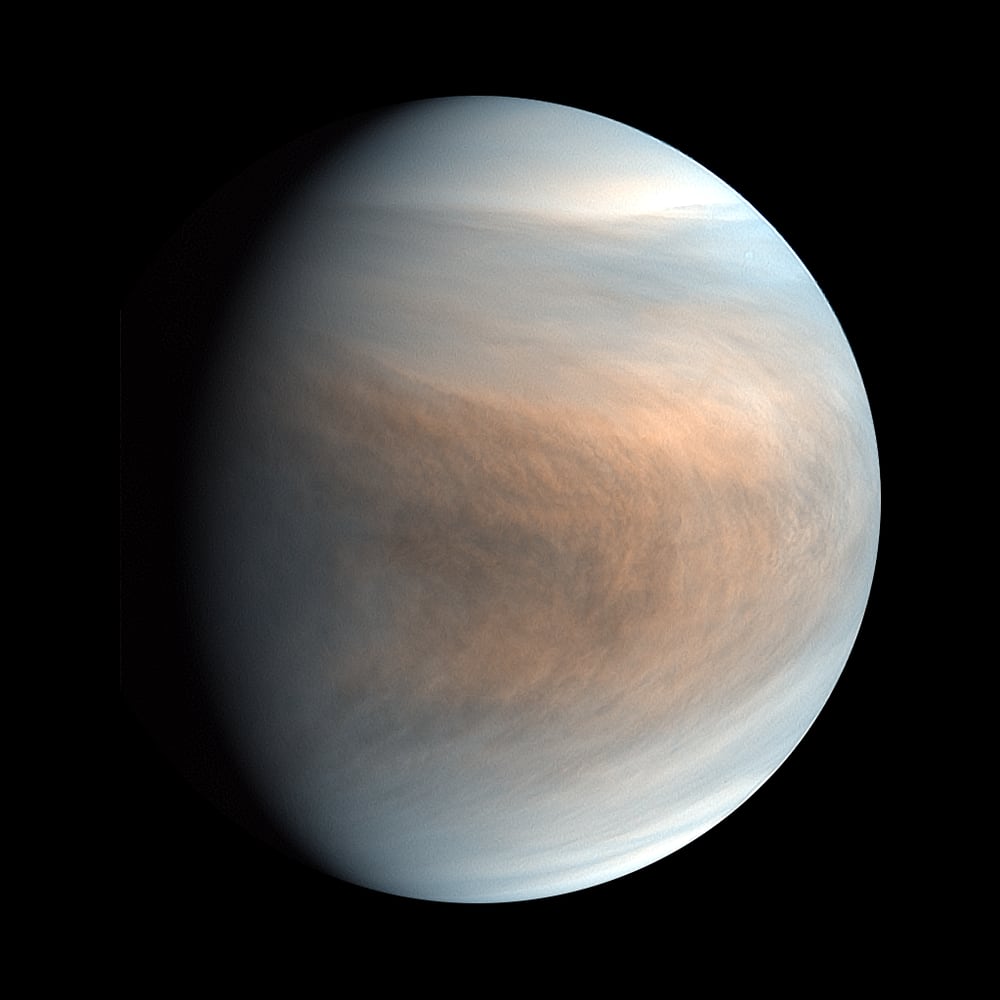

Venus is the infernal twin of Earth.

If a human could step on its surface, he would see everything orange, the sky very low and foggy, and he would die instantly, since the pressure there is equivalent to that at 1,600 meters under the sea.

Its composition is rocky, and its size is almost identical to Earth.

But its atmosphere is made of toxic gases that generate runaway global warming that heats its surface to more than 400 degrees, enough to melt lead.

By comparison, the high clouds of Venus look like Eden.

About 50 kilometers above the surface, the temperature is just over 20 degrees and the pressure is very similar to that of the Earth.

One of the first to propose that there could be life in the clouds of this planet was the scientist and popularizer Carl Sagan, who in 1967 published a study in

Nature

speculating that there could be macroscopic beings the size of ping-pong balls;

a species of jellyfish floating in the atmosphere specialized in living among toxic gases.

It was also Sagan who in life repeated many times a phrase that is very relevant to this finding: "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence."

More than half a century later, a team of astronomers from the US and Europe announce that they have detected "phosphine" - phosphane by its official name - in the planet's atmosphere.

Phosphine is a foul and toxic derivative of phosphorus.

It has been used as a weapon, as an insecticide and is a residue from the production of methamphetamine, a drug.

For years it has been known that the largest planets in the solar system, Jupiter and Saturn, generate phosphine by uniting a phosphorous atom and three hydrogen atoms in their inner layers, which are at more than 500 degrees, in a process totally unrelated to the presence. of life.

But phosphine also exists on Earth and its main source is associated with microbes that live in environments where there is no oxygen, including the bottom of some lakes, fecal waters and the intestines of animals, including humans, according to those responsible for the finding. .

In their study published today in

Nature Astronomy they

point out that the amount of phosphine on Venus is 10,000 times higher than what could be produced by non-biological methods.

The authors of the work have made a simulation of processes that could produce phosphine on Venus without the need for

Venusian

microbes

, including the impact of lightning, tectonic friction, the fall of meteorites.

None, they say, is anywhere near as possible as the presence of microbes in the clouds of Venus that are producing this gas.

The first evidence of the presence of this compound was captured in 2018 using the James Clerk Maxwell telescope, located more than 4,000 meters high on a volcano on Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

This is a radio telescope that picks up the waves that chemical compounds emit as they revolve around a planet.

The wavelength of the radio signals they emit allows us to know what compound it is.

In this case the phosphine detection was not conclusive.

A year later, astronomers used ALMA, another radio telescope located high in the Atacama desert of Chile, much more powerful.

The phosphine signal was much clearer.

But only one of the many radiation emission lines that this compound can emit was captured, exactly the one that has a wave with a length of 1.1 millimeters, explains to EL PAÍS Jane Greaves, an astronomer from the University of Cardiff and co-author of the study.

The researcher explains that she had the idea to search for phosphine on Venus independently in 2016. When her team found the first signal in 2017, she contacted Clara Sousa-Silva, an astronomer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who had focused her thesis on the detection of phosphine. as a biomarker.

The challenge now is to find more evidence of its presence on Venus.

"There are two other lines that could be captured from Earth, but it seems that they are not capable of penetrating the Earth's atmosphere," she says.

To see them you would need a space telescope.

Part of the scientists who signed the study published a detailed previous study in which they concluded that the presence of phosphine on a rocky planet like Venus can only be due to the presence of life.

In their study today they are somewhat more cautious.

"Detection of PH3 [symbol for phosphine] is not solid proof of life, just abnormal chemistry that we cannot explain," they conclude.

Sousa-Silva explains to this newspaper that the publication of this study is a call for help to the international scientific community.

"We did not find any alternative explanation for the presence of this compound on Venus and we need the scientific community to analyze our data and show us that it is possible to generate phosphine without the need for microbes to do so," he says.

The researcher points out that this study was rejected by

Science

, a much more prestigious scientific journal, probably because its reviewers did not see enough evidence to support the hypothesis.

She adds that her plans were to confirm these observations with infrared telescopes, one in Hawaii and another mounted aboard a NASA Boeing 747.

They have the permits, but the covid pandemic has prevented them from making the observations, he explains.

Phosphine does not have to be a marker of life, but can appear by processes outside it, says Kevin Zahnle, a planetary scientist expert on Venus who works at NASA and who has been one of the reviewers of the study.

"This is an unexpected discovery and worthy of publication, he emphasizes.

Zahnle acknowledges that phosphine is generally associated with life, but adds that it is actually an abiotic product found in the environment where living things decompose after death.

“Textbooks tell us that the way to make phosphine in the laboratory is by heating phosphorous acid.

I would start there to understand what is happening on Venus.

What is easier to imagine, drops of phosphorous acid that evaporate when falling or life in clouds?

I think the former ”, he explains.

"This study is robust, but life on Venus is not the most likely explanation," says Kathrin Altwegg, an astrophysicist at the University of Bern who has studied the presence of phosphorus in comets.

"There is still a lot to research on this topic, but without a doubt it is a very interesting result," she adds.

"It is an exciting detection, but it is very, very far from proving the existence of life", confesses Ignasi Ribas, astronomer at the Institute of Space Sciences (IEEC-CSIC).

Normally in this type of work, several emission lines are detected to confirm the presence of a compound.

This time there is only one.

"It's like having only one of the lines that make up a person's fingerprint," says Ribas.

“It is not clear that what they have seen is phosphine and, if it is, it is possible that it is due to non-biological chemical processes that we do not know about.

This is reminiscent of when the existence of life on Mars was proposed based on rocks with apparent fossil forms.

There were five inconclusive tests.

The sum of these can never be a solid conclusion.

In this case either.

We have to find more evidence, ”he adds.

"This study does not prove the existence of life on Venus, but it is revolutionary," says James Garvin, chief scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Center, who has been researching Venus for 40 years.

“An observation of a single chemical compound will never be enough to prove that there is life outside of Earth.

What it does do is change our point of view and show us that life can be in unexpected places ”, he highlights.

The world was still mired in the Cold War when the last human ship to visit this planet, launched by the former Soviet Union, entered Venus in 1985.

That was a generation ago.

We now know that Venus had an ocean millions of years ago and that life could have arisen there.

Garvin is leading a possible NASA mission to return to the planet and analyze the detailed composition of its atmosphere for the first time in the next decade.

"We will not be able to understand what is happening there until we return," he highlights.

You can follow

MATERIA

on

,

,

or subscribe here to our

newsletter

.