Riazor smells of the sea.

The storms sweep A Coruña and the saltpeter seeps through the cracks of the football field, on the edge of the beach.

Today, three-quarters of a century after its founding and after several renovations, the stadium looks more majestic than ever, and the waves can still be heard inside.

Titles and feats are exhibited in its guts.

Next to the access to the changing rooms, you can see the mixed area, set up like a gleaming television studio.

Opposite there is a large glass fishbowl so that managers and guests can watch the footballers go out while they taste Galician empanada.

Everything announces a First Class setting and the sensation multiplies when entering the field.

Huge markers with animations of the players accompany the

speaker's

presentation

.

It seems that at any moment the anthem of the Champions League is going to sound, but no, it does not sound.

In a few minutes, a simple Second Division B match begins in this magnificent 35,000-seat stadium. The Real Club Deportivo de La Coruña, one of the select nine champions of the League and the most unique phenomenon of the Spanish football boom at the turn of the millennium , faces a neighborhood team called Coruxo Fútbol Club.

“Puff”, ex-president Augusto César Lendoiro snorted a couple of days before when we sat down to chat at the Riazor hotel, near the stadium.

His snort is suspended in the air.

Lendoiro, 75, has thick hair, just a few gray.

He wears a

sport

jacket

and black walking shoes.

“Going from being seeded in the Champions League hype to being in Second B is hard for you.

But hey, in bad weather a good face, and for the rain, an umbrella ”, he says.

The man who designed Dépor's heyday - who caught it with a 20th-century debt, lifted it to the skies, and watched it fall from the top with a 21st-century debt - retains his plump and imposing appearance, even with a more youthful touch.

He no longer wears a tie or on his lapel the Ural badge —club he founded when he was 15 years old— that walked through Europe and showed like a bishop's ring in those eternal Betanzos champagne and omelette dinners where he closed unimaginable signings for a Peripheral Equipment.

In front of a glass of water, Lendoiro recalls that there were representatives of players who, upon landing in A Coruña for a negotiation with him, first went to the hotel to take a long nap "to be fresh for the night", as if they were going to play the game. final of a World Cup.

The players of Dépor and Coruxo take to the field at twelve in the morning on a mild Sunday in autumn.

The field is silent and the squawking of the seagulls is barely heard.

The feeling of strangeness is increased by the dystopian nuance imposed by the coronavirus restrictions: there are only 150 people in the stadium, and they do not occupy the stands, but the VIP boxes, where not so long ago you enjoyed watching Manchester United, Barcelona or Juventus.

Today Deportivo will beat Coruxo 1-0 and suffering, scoring this goal in the same goal where one day the first three goals of a formidable comeback against Milan entered;

where Bebeto gave a samba dance to a defender from Espanyol, or where Djalminha humiliated Madrid by making a

lambretta

pass

,

a maneuver so creative and complicated that you better watch it on YouTube.

With the club sunk, the memory of recent greatness and popular attachment to the shield survive.

"It's Second B, but we are 20,000 members," says Javier Fraga, from the Rompeolas peña, in front of his bar, a classic of the previous one in Riazor.

It's actually 21,000.

Almost 10% of the entire Coruña population.

Above the cups and the laurels, all the fans emphasize that the true heritage of the team is its social strength;

what Os Diplomáticos de Monte Alto de

O Dépor

sings

we are nós.

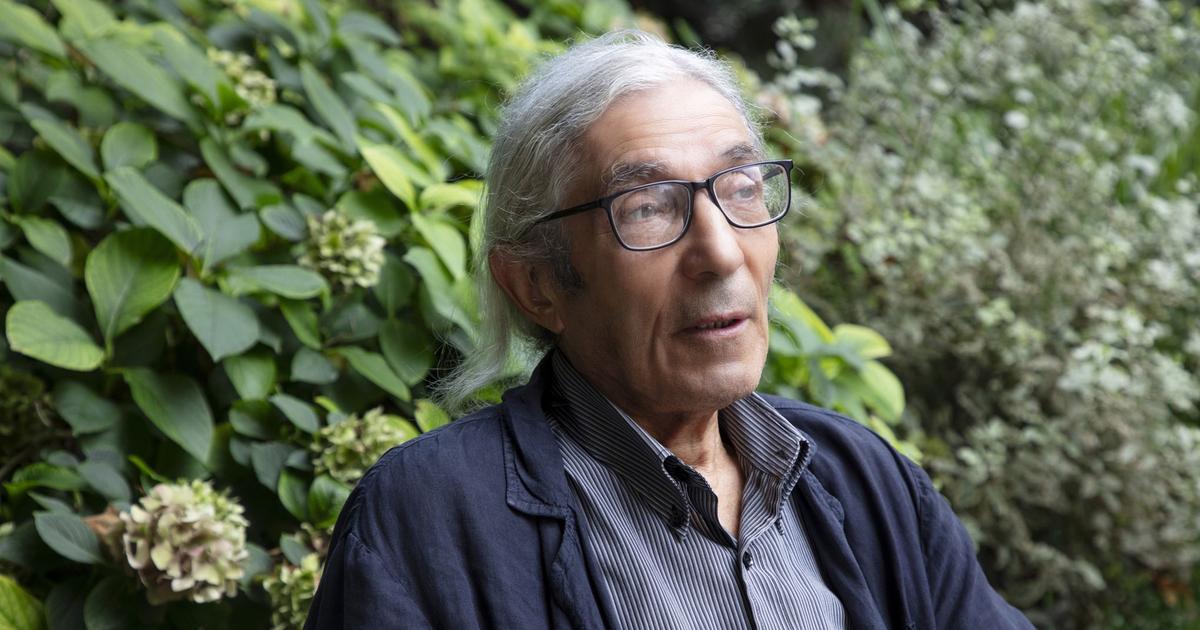

Former President Augusto César Lendoiro, in A Coruña, with Riazor beach in the background.

JORDI ADRIÀ

Three Soviet plans

June 1991. There is no room for a pin in the Plaza de María Pita, full of grandparents, parents and kids who obediently chant what the president shouts from the balcony of the town hall, with his name and his image of a joyful Roman senator.

"Barça, Madrid, we are here!"

Augusto César released such an ordeal during the celebration of promotion to First after 18 years out of the highest category.

“I just wanted to win.

I was not satisfied with participating, ”he recalls.

When Lendoiro took charge of the entity, in 1988, Deportivo had just been saved, precisely, from a relegation to Second B, had 5,000 members and owed 430 million pesetas.

"We didn't even have shirts, because at that time you also had to buy them."

As a shock strategy, a system "like the Soviets" developed.

It consisted of two three-year plans and one five-year plan.

Three years to move up, three to play in Europe, another five to win a title.

He was ahead of his own predictions, but that was not even dreamed of by that devoted crowd.

They only celebrated that the

longa noite de pedra

had ended

.

Just before the start of the June 1991 promotion game, a stadium roof caught fire from the launch of a flare.

The fans went down to the grass.

I was a child and I remember helping to hold a punctured fire hose.

The match resumed and Dépor won.

The

meigallo,

the spell that had prevented him from ascending the previous seasons,

was said to have been burned

.

Not for nothing was the coach of that team, and the architect of what was to come, called O Bruxo: Arsenio Iglesias, the paradigm of the village sage.

In the years that followed, Arsenio found himself with a dazzling team in his hands to which he applied his common sense and his doses of retranca.

At 90, the Brujo can still be seen walking around A Coruña on the arm of his children and protected by sunglasses.

A bronze bust pays tribute to him on the waterfront.

In 1992, at the end of his first year at Primera, Lendoiro got on a plane to Rio de Janeiro with a photo book of A Coruña and a Sargadelos ceramic necklace.

He is planted in the exclusive area of Barra da Tijuca and rings the house of José Roberto Gama de Oliveira, Bebeto, a consecrated star who was about to sign for Borussia Dortmund.

Before leaving, Augusto César takes out the Galician presents and hands them over to Denise, the footballer's wife.

"I told him that the beach that appeared in the photos —very sunny, because the image had been taken in summer— was like a small Copacabana," he says, pointing wily from the hotel to the Riazor beach, anything but tropical for three quarters parts of the year.

From Rio, Lendoiro jumps to São Paulo, where a serious and rocky young man named Mauro Silva was preparing to play a match at the Morumbi stadium.

"I wrote the contract myself at the hotel and Mauro signed it on a stretcher in the dressing room before leaving."

That boy would be world champion two years later and would become the archetype of the defensive midfielder.

Dépor-Coruxo in Riazor.

JORDI ADRIÀ

The new Deportivo was born the same summer that a stage of Spanish football was lit in which the League would become the best in the world and in which Barcelona, Madrid and other of its teams would shine in Europe.

In 1992, the vast majority were converted into sports corporations, which facilitated the entry of capital to sign.

The path taken in A Coruña, however, had a peculiarity: the partners who bought two shares would have the right to keep their seat, and a maximum share limit of 1% was imposed.

That resulted in a club with 25,000 owners.

Lendoiro defined it as "popular capitalism."

Mauro and Bebeto gave luster to a project that already had a great previous pillar.

Francisco González Pérez,

Fran,

had come to the city in 1988 from a village on the Galician coast.

They gave him an address for Calle de San Andrés and a name, Puri.

"It was the pension for those of us who came from abroad," he recalls.

"I shared a room with my brother José Ramón."

Four years later, Fran triumphed at the head of that team that was baptized by the press as Super Dépor after a victory against Madrid.

In the first year of his explosion - the 1992-1993 season - he encouraged the show among the great team.

The second -1993-1994- scared the Barcelona of Johan Cruyff, the

Dream Team,

to the point of giving him the League after missing a penalty in the last minute of the last game.

Overwhelmed by the historic opportunity, the shooter puffed out his chest, looked at the ground and kicked the ball into the goalkeeper's belly.

It was Miroslav Djukic, a very elegant defender who left Yugoslavia at the dawn of the Balkan war and who a few years ago was still working as a bulldozer.

The tender Super Dépor was made great by blows too hard to heal even in 25 years.

"I have never removed that thorn and it will never come out," admits Fran, back as director of the quarry.

The Rompeolas bar has photos of historic club idols on the wall.

To the left of the framed shirt we see Luis Suárez, from A Coruña and the only Spanish Golden Ball (in 1965 with Inter Milan), and to the right, images from the golden age of the nineties and two thousand: for example, the of the athlete of Cristo Donato lifting his shirt after scoring the goal of the match in which Dépor was proclaimed League champion.

JORDI ADRIÀ

By then sportsmanship had become an international phenomenon.

Galicia's greatest misfortune, the diaspora, is also one of its greatest assets.

The

year of Djukic - a

metonymy that every football player from A Coruña uses for the fatal penalty season - 4,000 athletes traveled to Birmingham to watch a tie against Aston Villa.

More than half did it from London, where they lived - or we lived: in my case, just that year, good aim.

Two clubs were created there and with them we traveled months later to Riazor for that League final.

The wild party of the emigrant who returned to his land for a day turned back into a funeral.

But there was no turning back on the fever.

Galicia also had its internal exodus.

Thousands of families from the countryside emigrated to cities like A Coruña in the sixties and seventies, populated the neighborhoods that did not appear on the postcards and gave birth to a generation of new urbanites.

They lived through the golden era of Dépor and with it they enshrined their identity until today.

An example is the Chaflán peña, founded in 2011, when they were already painting clubs for the club, but whose germ was those crazy nineties of goals and beer in the Os Mallos neighborhood.

Today his bar exhausts the hours before closing due to coronavirus restrictions with a talk from partners.

Most are over 40 years of age.

“We have many memories, but none like the suffering and joy of the first Copa del Rey, in 1995 against Valencia.

That is not forgotten ”, says Rafael Varela.

That was the team's first title and it also had an extraordinary story.

In the second part, we thought someone was throwing rocks at us.

It was hail.

The deluge caused the postponement of the final.

Four days later the game was resumed and the game ended.

That Cup closed the cycle of Super Dépor and gave way to another stage of a powerful and more airy Deportivo, marked by the accelerated changes of a Spanish football that grew and inflated.

With the

television

pay per view

came the great rain of millions to continue betting.

The glory

In the locker room, Dutch forward Makaay sucks Estrella Galicia bottles two by two.

A hairdresser dyes juggler Djalminha platinum blonde.

Fran hugs the utilleros.

On the screen of my mobile phone, a Nokia brick, pops up a foreign number.

It is Radio Rivadavia from Buenos Aires.

They want to talk to the Argentines.

I hand them the phone and they answer them practically under the shower.

It's May 19, 2000. Deportivo has just won the first League of the 21st century.

The fans invaded the field and took Fran ahead.

That shy man that Bebeto called “craque”, and of whom he said that because of his talent he could be selected by Brazil, was hauled on his shoulders by a crowd that took off his clothes until they left him in front of the cameras with underpants with the number 10. "The fatal pass.

But I wish I had had that experience more often, "he says in a cafe with his usual calm demeanor.

Celebration of the League of 2000. Photograph of X. Rey (Efe)

The captain, a survivor of the team from the early nineties, got the best: enjoying the Champions League.

Such was the historical anomaly that Dépor won the League and Atlético de Madrid descended.

From the shipwreck of this club, Lendoiro caught Juan Carlos Valerón.

Twenty years later, El Flaco is the coach of Fabril, Dépor's subsidiary, and maintains his indelible smile.

“I arrived and something different was breathed here.

I remember being in the changing room before going out, in the tunnel, and feeling, without saying it, that we were going to win.

We believed in ourselves.

It goes beyond the game, ”he says in a cafeteria opposite Riazor, recalling that team of Javier Irureta, a sober Basque coach from Trappist.

For seven years, the technician lived alone in a hotel room.

He had a wardrobe with more wardrobe depth than any big one, not very docile but winning, and he dosed his talents like a knitting machine: Makaay's hammer hammer and Djalminha's alchemy, Turu Flores' rubber ankle, talent a Bulk of Valerón and the great scoops of Tristán.

And, of course, Mauro and Fran.

Thus he remained in the elite of the League and the Champions for five years.

Thus he won a Cup final against Florentino Pérez's Madrid in his own stadium, the Bernabéu, on the day that the galactic club turned 100 years old.

The

centennial.

Sportsmanship got used to that irrational accumulation of successes.

Also the handful of reporters who followed the team.

I remember a victory at Old Trafford because of Tristan's goal, but also because it was my birthday and after the game the regular crew of the club's charter gave me a bottle of Jack Daniel's.

On those nights back from winning in Turin, Munich or London, the players sat down to comment on the game with journalists amid the cigarette smoke.

Despite its success, Deportivo still had a family ecosystem.

September 11, 2001 comes to mind and I see Irureta and Mauro sitting with us on the sofa in a hotel in Lille, France, watching in astonishment on TV how two planes crashed into the Twin Towers in New York.

Along with the Riazor stadium, Fran and El Flaco Valerón, two myths of the club today in its organization chart.

JORDI ADRIÀ

At that time, Dépor became famous for its comebacks in Europe, such as one against Paris Saint-Germain or of course that of Milan in the quarterfinals of the 2004 Champions League. It was the last great feat, a crushing 4-0 with an entire city blowing behind like the

north

wind

does over the Tower of Hercules.

There was already a demand to buy tickets to the Gelsenkirchen final when Mourinho, coach of semi-final rival Porto, arrived and, as he has always liked to do, he hit the psychological key at the previous press conference in Riazor: “I see you very grown up ”.

Bad augury.

Mockingly, our PA repeated the phrase before starting the crash.

They won.

The final of the Champions League was escaping and with it was also an era.

Call at midnight

December 2004. Since the writing of

La Opinion

, I mark the usual number very late.

It's close to twelve at night, but I know that after seven in the morning, Mari Carmen, the secretary, is gone, and that at that time there is only one individual left in the club.

The landline telephone rings in an office crammed with folders and papers, at the back of a labyrinthine office in the Plaza de Pontevedra in A Coruña.

The man answers as if from the bedside table in his house.

-Yes tell me?

"Presi, how are you?"

And Lendoiro answered.

It could have been to ask him about a possible signing - "there's nothing like that" - or to ask about the inauguration of a supporters club - "I think it's at eight in the afternoon ..." -.

Faced with increasingly giant and modern equipment, the Dépor maintained a domestic model.

It came to have almost 80 million euros of annual budget, but never had more than five employees.

The president locked the door with his set of keys.

Then he dispatched the team's signings in several restaurants.

But that day I called him because in the newspaper where he worked, we opened first with Deportivo's monumental debt and we wanted to ask him about it.

Noble but dangerous idea.

Lendoiro spoke for an hour winding through a dizzying tangle of numbers for a sports nib like me.

The president tried to value “the liabilities” of a club that was beginning to see sharks roaming around.

The bubble of Spanish football was being punctured and Dépor and many other clubs that went on steroids had to render accounts or fall into bankruptcy.

The A Coruña team would take more years to do so, but its model of continuous redoubling of the bet began to waver.

Above, the life cycle of the stars was ending.

In 2005, together with Mauro Silva, Fran,

O Neno,

the

one

man

club from A

Coruña,

retired

, without tributes because there was a fight between him and the president.

The patient Irureta was also leaving.

The lean cows arrived, without Champions and therefore without income that would reduce a debt of more than 150 million euros.

A bather on the beach of Riazor.

JORDI ADRIÀ

Lendoiro qualifies that risky policy, but does not completely rectify: “Maybe he would have measured in doing some things.

But not in selling our best players ”.

When he finally did it out of necessity, Deportivo collapsed under its own weight.

The fall

Juan Carlos Valerón, a World Cup winner, champion of several titles with Dépor and a sensitive spirit, chooses relegation as the culmination of his elite career.

“An indelible scene from my career?

I have it very clear: the 10 minutes after the final whistle against Valencia in 2011. I never saw something like this, a team that went down to Second, but was applauded by the people, ”he says.

That night, the canary, moved, apologized to the public and they cheered him on.

Him and 20 years of glory.

It was giving way to the worst decade in the club's history, but with unprecedented support: the following year there was a record number of subscribers in Riazor.

Thus he managed to return to First in a single season.

But it went down again.

And went back up.

And after barely staying four years, another bad season brought him back to Second.

That decade of suffering and passion in equal parts, of saw teeth and troubles, is represented like nobody else by Fernando Vázquez, a high school English teacher who had trained many clubs, but never the team of his heart.

Lendoiro went to look for him before leaving, in 2013, to try to avoid a decline.

He did not succeed, but it was close.

Already with a certain aura of dead lifter, he promoted it the following year.

Vázquez has trained Deportivo in First, Second and Second B. “After the descents there was never a social break, there never was, it is impressive.

I trained Celta and Betis after going down and it was a drama, ”says the coach who arrived at a club in a spin.

The last descent also brought a condition that caulked any cracks between the stands, the team and the board.

An external enemy: the president of the League, Javier Tebas.

The sudden postponement of the last game, against Fuenlabrada, which appeared in Galicia with several positives for coronavirus, while the rest of the day was played, turned on the Coruña.

Even more so when it was learned that the legal advisor of the Madrid opponent was the son of Thebes.

Sportsmanship maintains that the principle of equality was adulterated by breaking the unification of schedules on the last day.

The combination of results left Vazquez's team with no options, which even today is stirred up when asked.

Sitting on a bench in Riazor during the interview, he jumps up as if to protest to the referee and yells: “I feel helpless, outraged.

But let's see!

If the last matchday had not been played in 1994 and Djukic's penalty had not existed, Dépor would have been league champions! ”.

Through the streets of the city you can see masks with the face of Thebes crossed out.

However, despite being in Second B, the situation is not apocalyptic.

Under normal conditions, a team with a debt like yours would have all the ballots to disappear.

But at the most critical moment, last year, the local bank, Abanca, took over the majority of the club, a lesser evil for small shareholders, knowing that the entity would not turn its back on the great intangible heritage of the city.

At the moment it has sustained the brutal fall in income, reducing the budget by up to 70% compared to the 22 million of last year, but with some salaries much higher than normal in the category.

The reality on the pitch, however, is much more even, as we saw this Sunday against Coruxo and as we would see in December against Celta B, who would win 1-2 in Riazor.

I contemplated this sacrilege on the sofa in my house, stunned as in a bad dream that has lasted 10 years and in which we fall from the top of a building, in a downward, slow and sustained trajectory, with fleeting joys that are cushioning the impact as if they were the awnings of the balconies, although the fall continues, it does not stop.

The dream culminates that afternoon with the defeat against the subsidiary of the eternal rival.

And then the blow wakes us up, lying on the asphalt.

In the end, as in any nightmare, we are alive.

Broken, but alive.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/GCY4GRSKW5HKPN3OZH5NQLOOZM.jpg)