At the beginning of the eighties, Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber, legendary French journalist and politician, came to Spain to present his book

The World Challenge,

a sequel to the book dedicated to the American challenge itself that caused a real stir in public opinion.

In the introit of his lecture he conspicuously raised a small object barely visible to the audience and announced emphatically:

—This is a chip, something that will change the history of the world.

The chips were already known to the attendees, familiar with the use of computers and the still young computer technology.

They knew of its importance but many believed the prophecy to be exaggerated.

Chris Miller, professor at the Fletcher School at Tufts University, has come to demonstrate that that prediction has come true.

In

The War of the Chips

he gives a detailed account of the birth and evolution of Silicon Valley, the Silicon Valley, named as this material is fundamental for the manufacture of transistors and semiconductors or integrated circuits, which is the first name for chips. .

The word is a Latinism from English that originally meant splinter.

But it ended up being confused with potato chips, first, and then with silicon flakes, used as supports for said circuits.

Miller gives an extremely detailed history of the invention and manufacturing of these microprocessors that are going to change the world.

The military and geopolitical perspective of the story is interesting.

His description of World War II as “a rain of steel,” inspired by comments from Japanese soldiers, is consistent with the fact that it was a war of industrial attrition.

“The United States manufactured more tanks than all the Axis powers combined, more ships, more planes, and twice as many artillery and machine guns.”

Victory was decided by the superiority of steel and aluminum, but was sealed with the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the beginning of the nuclear age, protagonist of the Cold War.

After this, the current rivalry between Washington and Beijing “could be resolved by computing power.”

The chapters dedicated to the case of Huawei, a Chinese company that has suffered direct aggression from White House policy, stand out.

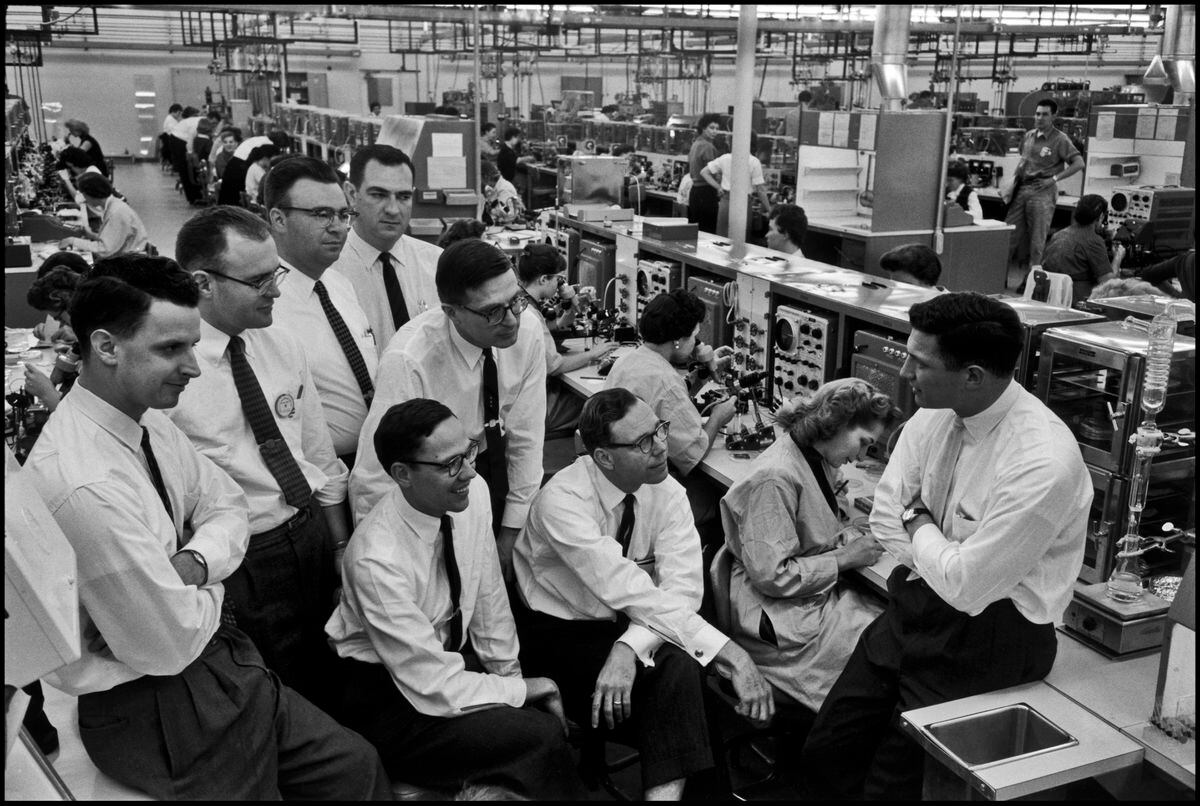

The history of chips is closely linked to the military strategy of the United States.

The group of engineers who invented them and ventured into their manufacture had the encouragement and support, also financial, from the White House.

The same whether it was the Apollo Program (the trip to the Moon), or the construction of Minuteman missiles or intelligent rockets.

If the bombing of Hiroshima was proof of the power of nuclear destruction, the Vietnam War served to test the versatility and usefulness of weapons equipped with information technology.

The invasion of Iraq and the war in Ukraine are so many occasions in which, through the annihilation of hundreds of thousands of human beings, the war efficiency of technological developments and Artificial Intelligence has been proven.

The author acknowledges that the early history of chips was closely linked to the Pentagon's plans: the Army was embedding chips "in all kinds of weapons, satellites, sonars, torpedoes and telemetry systems."

But the process acquired more spectacular profiles when in the seventies Bob Noyce, one of the pioneer inventors of the system, decided to promote mass manufacturing to produce chips intended for general use and not for specific needs.

Today our daily life is governed by the activity of those small technological chips, present in our refrigerators, microwaves, cars, telephones, televisions and countless other products, to the point that in 2020 "the chip sector produced more transistors than the sum of all the goods produced by all other companies, in all sectors, throughout all of history.

The book describes the Sino-American competition to achieve the primacy of technological power and the successes achieved by the Asian countries allied to America, particularly Taiwan, South Korea and Japan.

The chapters dedicated to the case of Huawei, a private Chinese company pioneer in the extension of 5G in telecommunications, which has suffered direct aggression from US policy, are interesting.

In 2018 I had the opportunity to speak with its founder, Colonel Ren Zhengfei, at its headquarters in Shenzhen.

Far from the penchant for prominence and spectacle that Silicon Valley promoters have demonstrated, he is a man consistent with the best tradition of Confucianism, courteous and thoughtful in his opinions.

Javier Solana, Javier Cremades and myself participated in the conversation.

When asked about the threat that the White House's hostile policy posed to his company, without making a gesture he simply drew attention to the magnitude of the Chinese domestic market, a formidable competitive advantage over the United States.

In the opinion of other company executives, this explains the American decision to expel them from their market and the restrictions imposed by the White House on the export of chips to China.

Washington's offensive has also been frontal in the countries of the European Union, including Spain, and the pressure continues.

The chip war is now at a fever pitch that threatens to escalate around the case of Taiwan, a champion country in chip manufacturing.

Politicians and rulers announce the end of globalization which, if it occurs on a large scale, will not be a peaceful end.

For his generals, on both sides of the front, the gold of the 21st century is not oil but data.

Europe, still absent from this conflict except as a victim, promises to make efforts to join it.

It is doubtful if he fulfills it that he can presume to claim his autonomy.

Although we will always have the other chips, the French fries.

Look for it in your bookstore

You can follow

Babelia

on

and

X

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I am already a subscriber

_