Employees at an electric motorcycle production chain in Qinglong, China's Guizhou province.Liu Zhaofu / Getty Images

The covid-19 pandemic has caused the largest contraction in the global economy in nearly a century.

Current forecasts suggest that world GDP will fall by 4.9% this year, the worst record since the Great Depression and a deterioration much greater than that suffered during the 2008 financial crisis. The worst, as the Monetary Fund recalled in June International (IMF), is that this "unprecedented crisis" is conditioned by an uncertainty also unknown about the evolution of the coronavirus and the path that the pandemic will have on economic activity.

The synchronized nature of the recession has severely hit commercial exchanges, which have been damaged both on the demand side, derived from the confinement imposed to control the virus, and on the supply side, due to the impossibility of maintaining levels. production and its transport.

The scenario drawn in June by the World Trade Organization (WTO) still maintained some confidence in the recovery of trade flows, although its calculations place the decline in global trade between 13% and 32% this year alone.

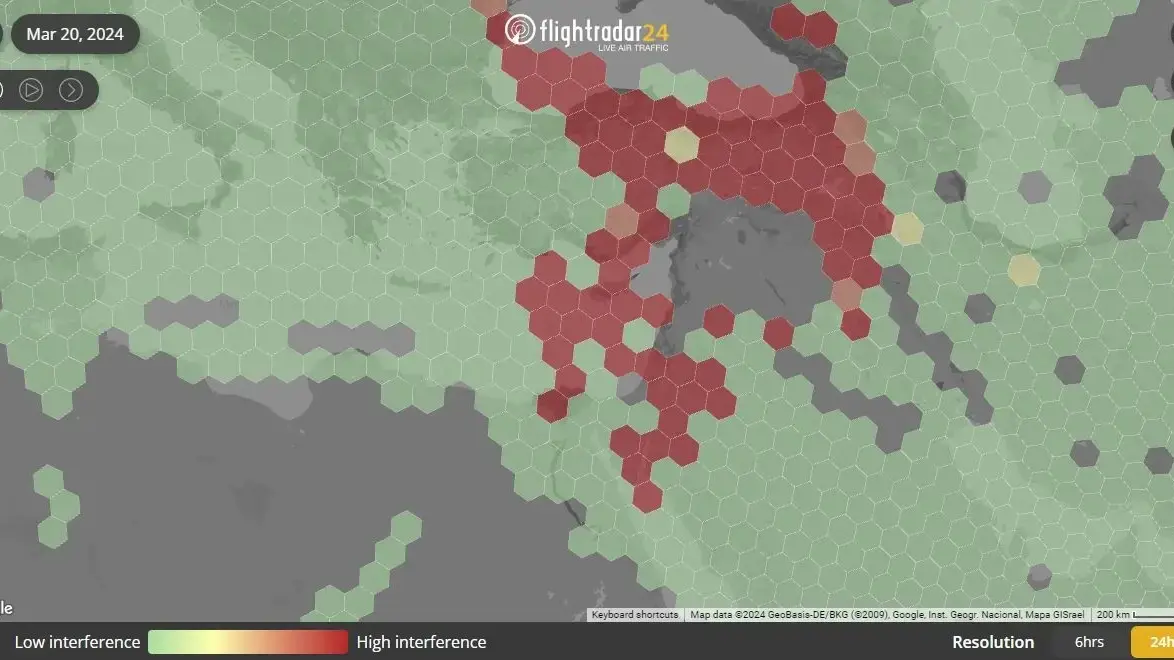

Foreign direct investment will fall between 30% and 40% and air traffic, both passenger and freight, will be reduced between 44% and 80%.

Figures that make a quick trip around the world as it was very difficult.

But the trade crisis came from further behind.

About the trade wars opened by the United States in recent years and its particular confrontation with China.

From growing economic nationalism and the imposition of trade barriers.

On the review of the taxation of large corporations.

The deglobalization process that these and other elements have unleashed.

In fact, global container shipping had already been on a downward path since the end of 2018;

the exchange of goods fell 3% in the first quarter of this year, before the health crisis exploded in all its harshness, and the exchange of services fell by 7.6%, according to data from the Unctad, the United Nations agency United for Trade and Development.

Historians agree that major

economic

shocks

tend to accelerate trends that are already underway, rather than drive major structural changes.

In this case, the pandemic has added layers of complexity to global trade amid growing geopolitical tensions and realignment of value and supply chains.

"The pandemic may end up redrawing the map of world trade," says the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) consultancy in a report under the same title.

Since the end of World War II, trade has been one of the engines of global growth, growing three times more than GDP between 1950 and 2008, according to Boston Consulting, at a time when there were notable reductions in tariffs and numerous liberalization trade agreements were promoted at the multilateral level.

It is the most recent stage of economic globalization that continues to this day.

Progress towards free trade came to a halt well into the 2000s and, coinciding with the outbreak of the international financial crisis and the questioning of the economic model, reversals of that opening began to be considered.

After the economic and social debacle that caused the Great Recession, the political climate also changed: the United Kingdom voted in favor of leaving the European Union and the arrival of Donald Trump to the White House caused the renegotiation by the first world power of the commercial treaties in force and the relationships with both its partners and its competitors.

Those changes were already there before the pandemic and had materialized in the form of setbacks in globalization and nationalism and in an emerging new bipolar order led by the United States and China, as explained by Cliff Kupchan, director of analysis at the consultancy Eurasia Group and senior official of the US State Department during the government of Bill Clinton.

“The main reason for the state to exist is to protect its citizens.

And the pandemic makes it even more evident.

The leaders become basically concerned about employment and have no time or money to devote to international affairs.

It is then that barriers are erected to the movement of people and capital.

And the State begins to play a growing role at the expense of the system, ”says Kupchan in an email exchange.

Bipolarity

Deglobalization and rising nationalism had already slowed the growth rate of world trade to slightly above, but very close to, the increase in global GDP.

The pandemic, as Kupchan rightly says, has accelerated this trend and the consequences of the new bipolar world.

The disconnection between the US and China that began in 2018 has picked up speed and trade tariffs and import and export quotas have now added strong limitations to the exchange of high-tech products, the movement of people and even within the academic world .

“The pandemic is the driving force behind the 2.0 disconnect.

Now is when global trade will be affected the most because countries will try to be more self-sufficient.

Healthcare products, the data industry and tourism will be hit hard.

Health is going to become a strategic sector and the States are going to accumulate supplies of ventilators, protective masks and medicines and they are going to want to reduce their dependence on countries like China and India ”, emphasizes Kupchan.

By mid-April, more than 80 countries had decreed bans on the export of medical supplies and personal protection products necessary to fight the coronavirus.

While most of those barriers have since been lifted, that reality has ushered in a change that promises to be lasting in global trade.

This is what French President Emmanuel Macron defined as the need to guarantee "health sovereignty" with a new industrial and commercial policy.

Or Donald Trump's appeal to national security to restrict trade with China, a pretext that can be used for many economic sectors.

All of them, different ways of calling greater protectionism in the commercial sphere and examples of the growing role of the State in the economy.

A role that is here to stay and that takes many forms.

The governments' response to cushion the impact of the crisis has resulted in an increase in public spending and loss of income for the G20 countries equivalent to 6% of their joint GDP, to which must be added another 6% injected in the form of loans, participations and guarantees, according to a note by Joanna Konings, international trade expert at ING Economics.

Although this public support has been essential to keep companies afloat and avoid even more devastating consequences of the economic collapse, "many of these public aid may end up having long-term consequences that are felt on commercial exchange flows", Konings points out.

It is true that not all the subsidies approved by the pandemic have an impact on international trade - aid to hairdressers or cultural activities, for example - but those that do already affect 3% of global exchanges, according to Global Trade Alert, the initiative launched by the Center for Economic and Policy Research in November 2008 to monitor the interventions of different countries that can affect foreign trade.

That 3%, Konings emphasizes, is a similar percentage to that of the trade affected by the trade war

US-China, which will not weigh so much on consumer and business expectations, but it will be an added burden for the recovery.

Tax increase

Changes can also be expected that may impact trade on the tax side.

Because the pandemic has expanded the powers of governments, but it has also changed what voters expect in return.

Among other things, better public health and that will require new and higher revenues to finance it.

Since the 1980s, liberalism and globalization have led to a global race to the bottom of corporate taxation that may be coming to an end.

Technology companies were already in the sights of the States before the pandemic, bogged down in obsolete tax structures that do not correspond to the current relocation of production and the way of providing services.

The needs derived from the coronavirus add argument to this review of structures, especially since technology has been some of the companies that have benefited the most from the pandemic.

"Taxes are likely to go up to finance increased public spending, although the trend will continue only until full employment levels recover," said Neil Shearing, chief economist at Capital Economics.

On the other hand, strategies such as the Green Pact promoted by the European Commission to reduce emissions of polluting gases raise the possibility of imposing an emissions tax on imports.

A measure that will cause a break with the existing status quo and that "can redefine global competitiveness in a wide spectrum of industries," says Boston Consulting, and with it global commerce.

This complex scenario means that companies will have to adapt their production and supply chains to make them more resistant to possible

shocks

derived from future crises, but also from geopolitical confrontations in order to avoid being caught in a tangle of tariffs, sanctions , closures or market access restrictions.

Henceforth, any type of “foreign” status in any part of its structure will carry additional risk for companies.

Covid-19 has revealed the threat of concentrating too much production and supplies in a few locations with low costs, but physically far away and without sufficient inventory management.

"The tendency to outsource production is going to decrease notably, there is a generalized tendency for governments to promote a policy in favor of repatriating part of that production.

In some cases, because they are products that have been considered strategic after the pandemic, such as those related to health.

In other cases, due to political or technological reasons, such as the barriers imposed on 5G developed by Huawei, ”explains Erik Nielsen, Unicredit's global chief economist.

This "great return", to call it somehow, will affect some of the world's largest economies such as Germany, the world's leading exporter that in this pandemic has seen China become its main market, ahead of the United States, according to data from Unicredit, which links it more than a structural change to the rapid recovery of the Asian economy.

“Germany and the Netherlands have already started to adopt policies to develop their domestic market because they are highly dependent on exports.

Although in the European case, the repatriation of production can be done throughout the territory of the European Union, not necessarily to national territory ”, points out Nielsen.

As if that were not enough, the world trade situation is complicated by the lack of institutions that allow coordinating a global response to the crisis that guarantees the development of free and fair trade.

After the financial crisis of 2008, countries gathered around the G20 to agree and adopt many of the measures that in this crisis have allowed the authorities to act quickly on fiscal and monetary policy.

They also pledged not to adopt protectionist measures that could aggravate the crisis and were equipped with instruments to monitor the trade policies of the respective countries.

Today there is no trace of a minimum coordination at the global level.

And when it comes to trade, even the future of the WTO itself is up in the air in the face of the Trump Administration's strenuous attempt to take powers away from the organization.

First, blocking its role as arbiter in commercial disagreements and more recently, refusing to approve the organization's budget.

Some US officials have even left the door open to the possibility of the US leaving the WTO as it has done with the World Health Organization in the midst of a pandemic.

The WTO is also immersed in the process of selecting its head, due to the sudden resignation of its director, the Brazilian Roberto Azevedo, which takes away even more authority at a time when it is being strongly questioned.

Although most of these changes have been brewing for some time, the pandemic has accelerated many of them and in other cases latent trends in global trade have emerged.

The coronavirus has acted as a catalyst for those changes that are beginning to redraw the new map of world trade, despite the fact that that map is still somewhat blurred to this day.

"One of the keys that historically define the beginning of a new era is disorder, a certain chaos," emphasizes the chief strategist of Deutsche Bank Research, Jim Reid.

“It doesn't have to be something negative, on the contrary, it can serve to clean up the excesses of the previous stage.

The worrying thing is that this time these changes are taking place in many areas simultaneously and when that affects structural aspects, disorder is what ends up defining the new era ”.

This is what Reid has called his latest report, The Age of Disorder, where he warns that, looking to the future, the biggest mistake of companies and experts would be to extrapolate the trends of our most recent past.

The evolution of the pandemic and the recovery of the global economy and trade remain unknown.

But it seems increasingly clear that, by intensifying the geopolitical and economic tensions that previously existed, the impact of the pandemic will be long-lasting.

And going around the world as it was until January seems the least likely option.

Sean Doherty: "Global economic governance requires cooperation"

Few institutions are as tied to globalization and trade liberalization as the World Economic Forum (WEF).

Sean Doherty, its director for the area, defends the importance of international cooperation to coordinate responses to the crisis.

QUESTION.

Do you think that the measures adopted by the governments in the face of the pandemic are being positive?

REPLY.

It was an interesting reaction.

Countries have focused more on building resilience and securing supply chains, mainly for health products of course, and there has been a notable involvement of governments in the economy.

And there I would like to highlight two things.

On the one hand, that resistance is achieved through diversification and it does not seem that the tendency to repatriate the production of these goods is the best way to ensure that resistance in the future.

On the other hand, that this prominence of the States occurs without there being, unfortunately, a forum where to debate all the aspects that this new role has in terms of taxes, investment, competition, etc., and that would require coordination.

P. On this occasion, nobody seems to question the role of subsidies and public aid.

R. Given the magnitude of the crisis, it is evident that certain aid is necessary to sustain the activity.

What should be guaranteed is that they are produced with transparency and rigor.

That is, for example, the center of the debate between the European Union and the United Kingdom in the face of Brexit.

But it's not always clear what its purpose is.

Q. What do you mean?

R. For example, now appeals to national security as an argument to stop investment from entering the country or prevent the so-called "crown jewels" from passing into the hands of a Chinese company or an investment fund in Singapore.

And it is not clear that the true motivations are related to safety.

Q. There doesn't seem to be much cooperation in that regard.

R. Exactly.

Perhaps historically there was less need to discuss these issues because trade was easier.

Now global economic governance has more nuances and requires more cooperation in the digital field, taxation, state aid or competition.

Tariff war and a weak dollar

"Trade wars are good and easy to win."

It was the maxim repeated over and over by Donald Trump as soon as he became president of the United States.

But reality stubbornly insists on not agreeing with him.

Economists explain that Trump has used trade tools - tariffs, sanctions, and quotas - to fix a macroeconomic problem, like the trade deficit, and unsurprisingly, it hasn't worked.

The United States registered the largest trade deficit in the last 12 years in July, reaching 63.6 billion dollars, and with China alone, the deficit grew by 11.5% that month to 36.6 billion.

Although the figures are distorted by the effect of the covid-19 pandemic, it does not seem that the data will improve in the near future.

Hence, the trade deficit has ceased to be one of Trump's campaign mantras and has disappeared from his attacks against China and other countries with whom he has trade disputes.

Trump has redirected his strategy to the search for agreements that guarantee an increase in import quotas for US products, which naturally comes at the cost of reducing imports that these countries make from third parties.

To the equation we must recently add a weak dollar, which facilitates US exports, softens the impact of imports on the trade balance, adds inflationary pressures to the economy, —which is the new declared objective of the Federal Reserve— , and stimulates internal investment.

All at a time when the capitalization of large US technology companies has skyrocketed to $ 9.1 trillion, above the $ 8.9 trillion in which the entire European market is valued, according to a Bank report. of America Global Research.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/H4OQQFWP7M2WIJYAVWO45FAOKI.jpg)