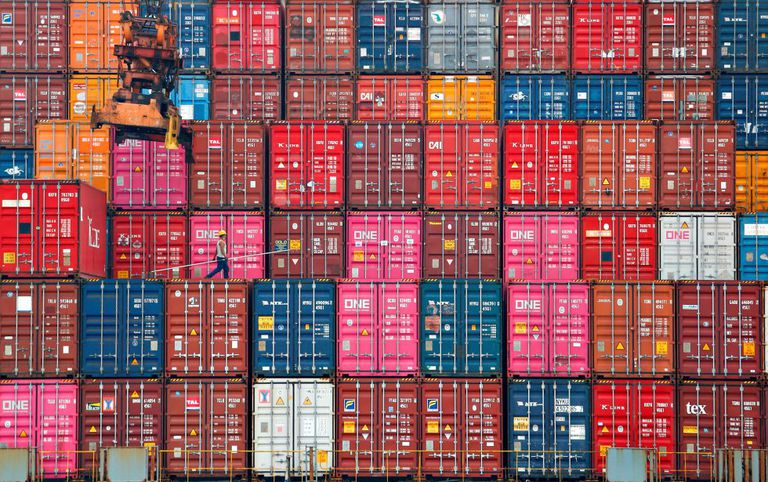

A worker walks on stacks of containers at the port of Tanjung Priok in Jakarta, Indonesia. Ajeng Dinar Ulfiana / Reuters

Just a year ago all the pools went through a long season of emerging in economic hell.

Everything pointed in that direction: the pandemic was primed, beyond Europe and the United States, with Brazil, India and Mexico, three key countries of the developing bloc;

and Latin America had to lose: the raw materials, on which it continues to depend so much, had gone into a tailspin.

Everything, in short, was working against him.

But that diagnosis did not take into account an essential variable: that in a hyperglobalized world what the rest of the actors do matters as much or more than you do.

The heavy artillery with which the great central banks of the planet has gotten out of the crisis has not only acted as a firewall in rich countries, but has also allowed emerging countries to recover in record time from the initial flight of money that brought with it the sanitary shaking.

And yet, this globalization to the cube also applies in the opposite direction: if the large issuing institutes shake their hands and slightly back down on their road map, the developing world has the upper hand.

When the foundations shake, the emerging ones are always the weakest floor of the world economic edifice.

And the earthquake of the pandemic is unprecedented: in a single month, March 2020, the flight of capital invested in debt and emerging stocks touched 100 billion dollars, according to data from the Institute of International Finance (IIF, a kind of global banking association).

The money, always fearful and mostly coming from rich countries, was heading back in one fell swoop, at a speed that invalidated any comparison with any previous episode: both the global financial crisis of 2008 and the

taper tantrum

of 2013 - when the Federal Reserve slipped that it would start withdrawing stimulus earlier than expected, causing a domino effect - were a long way off.

The recovery from this abrupt stampede by investors, however, has been just as swift.

By June, the bleeding had already stopped and the inflows of money in emerging markets were already equalizing the outflows.

And before the end of the year, they had already returned to pre-crisis levels, a milestone that took years to reach after the global financial crisis.

The initial flight of investors was “really violent;

kind of like a whiplash, "in the words of IIF economist Jonathan Fortun, while in the Great Recession it was" like pushing a button in slow motion. "

"But the interesting thing," he adds by phone, "is that the return has been as strong or more."

Less than a year ago, Fortun acknowledges, “we all thought that the emerging countries were going to have many more problems, that remittances [the money that migrants send to their families] and raw materials were going to sink”.

The former, however, have endured surprisingly - a phenomenon that many analysts still seek an explanation for beyond the income maintenance policies in their destination countries - and the latter have recovered at a speed that few were capable of. predict.

"We were afraid of the four horsemen of the apocalypse and it has become much less," he admits.

Inflation returns to the pools

The OECD significantly improves its forecasts for 2021 in the three largest economies in Latin America

Extreme poverty in Latin America marks its maximum in 20 years due to the coronavirus

What is the reason for this radical change in pattern compared to previous episodes of volatility?

Both the IIF economist and José Pérez Gorozpe, head of research and analysis for emerging markets at the risk rating agency S&P, allude to the very different response given this time by the two central banks of the planet - the Federal Reserve (Fed) the US and the ECB - with an endless free bar of liquidity and the promise that they will not lift the accelerator prematurely.

With the interest rates on the debt of rich countries at record lows, if not directly negative, and the stock markets at record highs, both fixed income and equities in the developing bloc have shone with their own light, leading back to the same investors who turned their backs on it at the beginning of the health crisis.

"For months they have been the only place where investors have been able to find returns," emphasizes Pérez Gorozpe.

Clouds on the horizon

The game is well on track, much better than anyone could have anticipated, but it is by no means won.

In February, the return of capital has slowed down, after the return offered by the US 10-year bond has shot up 60%.

And at those levels, for many, it is no longer so compelling to take the added risk that comes with investing in middle-income countries.

Not only that: with the multimillion-dollar

Biden plan

already approved, the chorus of voices of those who warn of a potential overheating that would bring inflation and that would force an early normalization of monetary policy has grown exponentially.

Something that would completely change the script.

It's a shock to see EM outflows so soon after 2020. The good news is it's all about the US bond market sell-off & Fed speak.

In other words, it's contained & fixable.

The bad news is that things need to get worse for the Fed to change its messaging to slow rising US bond yields.

pic.twitter.com/9049Zhaayv

- Robin Brooks (@RobinBrooksIIF) March 15, 2021

“The mere existence of a debate on inflation hurts the entire bloc and there are already those who are warning of a

taper tantrum

2.0.

Unlike a few months ago, some risks are beginning to be seen and the liquidity frenzy has slowed down quite a bit in the markets, but I think the Fed has learned from its past failures and will not fall again ”, emphasizes Fortun.

"The key now is to avoid unforced errors", ditch making use of the tennis simile.

Whether or not the leader of US monetary policy has learned its lesson, whose pulling power is still incomparably greater than that of the ECB, both the IIF economist and his peer from the

S&P

rating

agency

believe that from now on a path of differentiation in which middle-income countries will not be treated as a monolithic bloc, but their individual situation will be valued “much more”.

Not everyone would be equally vulnerable to a rate hike: those with a more unbalanced balance of payments, such as Argentina or Turkey, would be cannon fodder.

Also those that dragged “important fiscal challenges” from before the pandemic, such as Brazil or South Africa.

But in almost all cases, Pérez Gorozpe closes, "the imbalances are much smaller than in previous crises."

In the capitals of the block, from Johannesburg to Jakarta, fingers crossed that this is how it is valued.

And why inflation does not run rampant thousands of miles away.