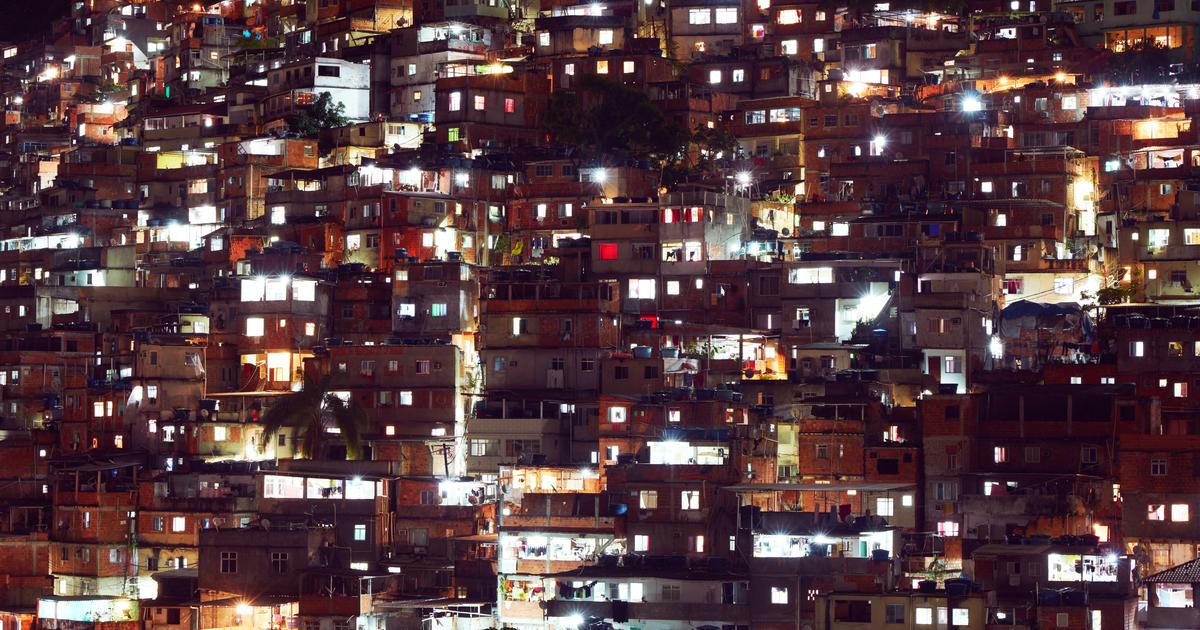

A shopping street in downtown São Paulo (Brazil), on December 30.NELSON ALMEIDA (AFP)

The recovery, although somewhat weaker, runs its course. Slight tweaks to the margin, the macro picture hardly changes: the world will grow 4.1% in 2022, two tenths less than expected now, and 3.2% next, one more, according to the projection published this Tuesday by the World Bank. The risks, however, are multiplying: omicron adds to the outrageous rise in prices - with the possibility of the dreaded de-anchoring of inflation expectations, underlines the lender - and to "financial stress in a context of record public debt." However, the main focus of concern of the Washington-based organization is in emerging economies, for which it predicts curves: "Given the limited fiscal space to support activity if necessary, these risks increase the possibility of a landing abrupt",It is read in the last global perspective of the multilateral, in which it is warned that if any country has to restructure its debt, it will find "more difficulties to achieve it than in the past."

With monetary and fiscal policy "in uncharted waters", the World Bank economists emphasize, the prospects for interest rates and rising inflation are "not very favorable" for the interests of emerging markets. Two figures condense much of the growing concern about what may be to come. First, the yield on the US 10-year bond is already around 1.8%, almost four times above the lows of a year and a half ago and at levels similar to those at the end of 2019, when the virus was neither present nor affected. He sensed and the public debt of developing countries had not yet skyrocketed. This means that the riskiest investments in emerging markets have a new risk-free competitor. Second, the global reserve currency, the dollar,It shows an upward trend that is sowing uncertainty among countries with hard currency debt.

Temporary goodbye to the growth premium for the developing world

The World Bank's rhetoric partially collides with the colder figures: while the growth forecast for advanced economies falls by four tenths this year and two tenths next, that of emerging economies is two tenths better for 2022 and only one worse for 2023. Regarding In the run-up to the health crisis, however, the reality is quite another: if in 2019 the rate of expansion of developing economies more than doubled that of their advanced peers, today it is barely 30% higher.

Moreover, the technicians of the Washington-based organization warn that, while investment and GDP will return to the prepandemic path next year in rich countries, in those of middle and low income they will remain "considerably below". The reasons? Lower vaccination rates, less margin on the fiscal and monetary flanks, “deeper” scars from the pandemic and record debt in most of the bloc's countries, which will probably continue to grow given the “weakness” of their collection systems. The solution? "Strengthen global cooperation for prompt and equitable vaccine distribution." The percentage of the population that has been pricked in middle-income countries is around 20 percentage points lower than in their wealthy peers. And in the poorest it is still very small, below 10%.

Large variations between countries

Regional differences in the emerging group are greatest.

For East Asia and the Pacific (which includes China, Indonesia and Thailand, among others), the pandemic will end simply as an episode of slower growth: in 2020, while the world economy plummeted 3.4% in the largest recession synchronized as far as memory goes, they grew a small but very remarkable 1.2%.

In 2021, with the recovery already launched, its expansion was around 7.1%, the highest among middle-income countries.

And in both 2022 and 2023 the World Bank expects it to easily exceed 5%, making it the envy of the rest of the bloc.

The emerging countries of Europe and Central Asia (with Russia, Poland and Turkey as the greatest exponents) also managed last year to more than recover everything that had been set back in 2020. South Asia (India, Pakistan or Bangladesh) and Africa are in a similar situation. Sub-Saharan (led by Nigeria, South Africa and Angola): both fully recovered their pre-crisis level of activity in 2021, and both will grow somewhat more vigorously than before the pandemic both this year and next.

The islands dependent on tourism, the hardest hit

The cases with the greatest lag - and therefore also the most worrying - are those of the Middle East and North Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean. In both, despite the rising cost of raw materials - of which they are net exporters - the rebound last year was insufficient to completely close the economic gap opened by covid-19 and they will have to wait until mid-2022 to recover by Complete the ground lost during the health crisis. Among the large Latin American countries, Mexico stands out, which will not achieve that goal even in 2023. Yes, the other two largest economies in the region will do so: Brazil, which already returned to precovid GDP in 2021; and Argentina, which, although constantly battered by inflation and debt, will also do so in the early stages of the current year,well ahead of what was initially planned.

More information

The Federal Reserve and the strong dollar scare developing countries

The large numbers, however, hide very distant realities. In its latest review of the global economy, the World Bank provides an interesting reflection to understand the dimension of the coup for some emerging countries: measured in per capita income, the recovery “may leave behind those who suffered a major setback in 2020 , like the islands that depend to a great extent on tourism ”. This annotation applies to many island territories in the Caribbean, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean. But not only: more than half of the economies of East Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and North Africa will close 2023 with a per capita income lower than at the end of 2019, before the pandemic. The proportion grows to two-thirds of the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Inequality between countries returns to levels of a decade ago

The impact of the pandemic has been and continues to be multidimensional, and it is increasing inequality on all fronts.

According to World Bank calculations, the weaker recovery of emerging countries compared to their rich peers will bring inequality between countries to 2010 levels and will reverse - even partially - the improvement recorded in the last two decades.

In emerging and developing countries, it should be remembered, two out of three people live in extreme poverty around the world.

Within each society, the “preliminary evidence” also points to a deepening of the cracks between social strata, a trend that seems far from ending: “In the medium and long term, inflation - especially in food - and the disruptions caused to education may continue to increase inequality within countries ”, write the technicians of the multilateral.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/3FI7KHR4GI7ABUOQDZ3ENWASZQ.jpg)