Thunder was heard throughout the town.

The tongue of fire ascended to the sky as if it wanted to devour the clouds.

Then only confusion and smoke: a huge black column rising above the mouth of the Guadalupe mines.

It was March 31, 1969, and in Barroterán a gas explosion had just killed 153 men.

It was the biggest mining tragedy of the last 100 years in the coal region of Coahuila;

the one that began to attract attention on this land where coal is called red because of the blood that is spilled to extract it;

which caused a more solid record of the victims to be started.

A place forever associated with ore and death, which these days when 10 workers remain buried at the bottom of a well in Sabinas, just half an hour away, resurfaces in memory and conversation.

“I remember when it exploded.

We lived there in Barrio Cuatro and we heard a very ugly sound.

My brother was on the first [shift] and my father was on the second.

My dad got it.

I went out to the mine, you could see a black smoke in that direction.

If you saw how long that lasted… the men were left under the ground or burned to death”, recalls Modesta Araceli Robledo (61 years old) one hot afternoon in August.

She was only eight years old when the accident happened.

Her father, Sixto Robledo, was one of the deceased.

“My dad was taken out on the fourth day.

My brother stayed a whole day waiting in the mine with streams of people who gathered.

When they took them out he went in boxes.

If you saw how bad my mother got, cry and cry.

The miner Sixto Robledo Rangel, one of those killed in the 1969 explosion. Pasta de conchos family (FAMILY PASTA DE CONCHOS)

A single fan served to ventilate two huge mines that had just been connected by a gallery.

Although it is not clear what caused the explosion, the most widespread hypothesis is that the person in charge of measuring the gas levels lit an oil lamp and his spark triggered the fire.

All the bodies were rescued complete, except his, which was found mutilated, says Omar Navarro (26 years old), who has always lived in Barroterán and is part of the Pasta de Conchos Family, an organization that fights to enforce the labor rights of the miners.

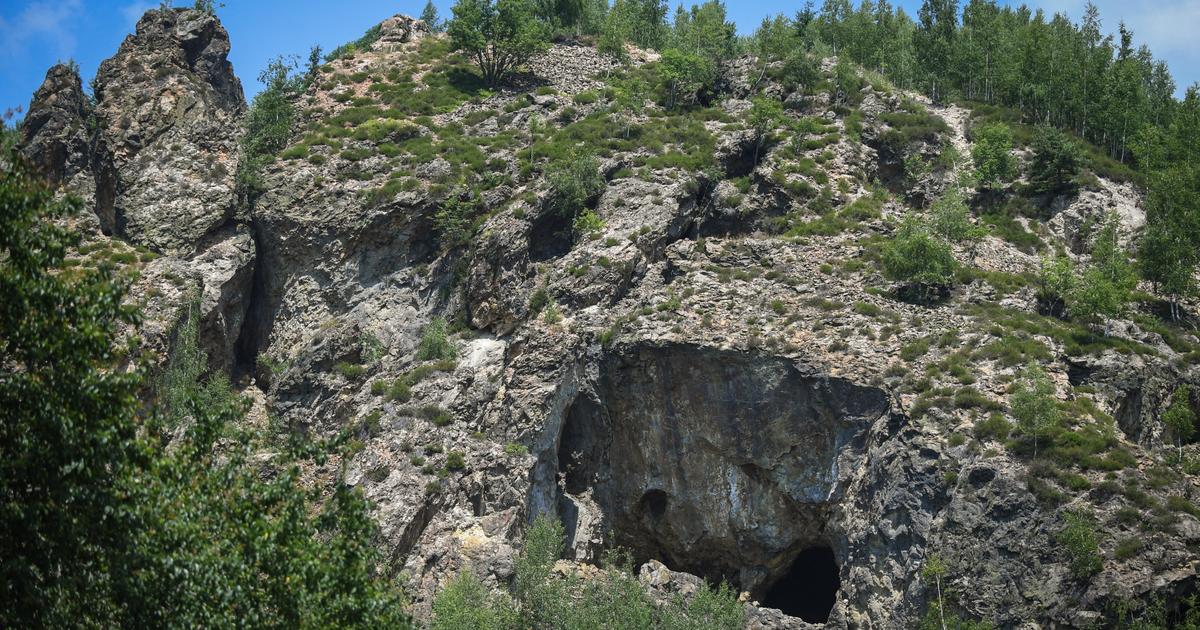

The cross stands out against a sun of molten lead up there on the top of the hill.

At their feet, the ruins of what were once the Guadalupe mines are little more than dust and rubble, remnants of trash, and a few thorn-like bushes.

A huge collective tomb crowned by a single crucifix.

The place where the mouth of the coal mine used to be is less than 20 meters from the main road of the town.

Cars pass by and neighbors look strangely at strangers taking photos of what is now just a vacant lot.

The abandoned ruins of the Guadalupe mines, where a gas explosion killed 153 miners in Barroterán, in 1969.ANTONIO OJEDA

Barroterán was never the same again.

In the collective memory, it ceased to be a town to become a cemetery, in a huge tribute to the fallen miners, with statues and roundabouts in his honor.

The tragedy was of such magnitude that the Spanish edition of

Life

magazine carried it on its cover, with the headline

Barroterán's Hell

and a photograph of one of the miners who participated in the rescue attempt, his face blackened with coal and a lost expression on his face.

“I think the explosion is an emblem [of the place], unfortunately.

It has marked history a lot, people remember it almost almost bragging.

The years go by and the relatives continue to feel their pain”, explains Navarro.

Navarro attacks the narrative that was installed in the town, the commonplaces that extol mining pride and see coal as a collective identity, blood of their blood.

He says that businessmen in the region take advantage of this story.

It is easier to talk about heroes who sacrifice for their community than about victims of poverty.

"They don't die from coal, they die from the terrible working conditions," he concludes.

He, against the odds that he sentences the young men of the area to the wells, has always resisted going down to the mine.

He jokes that his finely built body wouldn't allow it.

But he has earned his living so far in the hardships of the maquilas and with the savings he is studying audiovisual communication.

He wants to be a filmmaker, to be able to shoot movies in Coahuila,

A man rides a bicycle in one of the streets of Barroterán, on August 14, 2022. ANTONIO OJEDA

The reality is that tragedies are repeated on this earth with traumatic regularity.

A bleeding et cetera.

In 2001, 12 men died in the La Morita well, also from a gas explosion.

The same thing happened in 2006 in Pasta de Conchos, where 65 workers died, and 63 of their bodies remain unrecovered.

In June 2021, seven people never left the galleries due to a landslide in Múzquiz.

The last case happened on August 3 in a Sabinas well.

The rescue efforts of the 10 day laborers continue and the families hope, against all odds, to see them alive again, almost two weeks after the collapse.

These are just some of the examples of a region that has seen more than 3,100 miners die since it began extracting coal in the 19th century, according to the count kept by relatives of the victims.

The Barroterán explosion not only ended the life of Modesta Araceli Robledo's father.

He also sentenced her to a life of abject poverty.

She, four sisters and a brother lived with her mother in a house bought from the state company that exploited the mine, the Guadalupe Mining Company.

When her parent passed away they still hadn't finished paying it.

One of the managers, Pablo Guzmán, expelled them from the residence with threats and extortion.

"My mom was desperate," recalls Robledo.

Statue in homage to the 153 miners killed in a gas explosion in the Guadalupe mines in Barroterán in 1969. ANTONIO OJEDA

The woman, alone and caring for six children, had to make a living as best she could, sometimes serving in wealthy households, other times begging in the wealthy neighborhoods of Sabinas.

They managed to buy another residence in Barroterán, where Robledo still lives.

The house is falling apart, the beams are chipped and the walls have gaps that threaten the entire structure.

Robledo has no income, he can no longer work.

His legs are more bone than flesh and his hands and knees have huge knots from arthritis.

She can now only tell her story, point out the culprits and hope that someone will listen to her.

Every Barroterán neighbor old enough to remember the explosion has their own story of loss.

María Pecina was born in 1942 and by 1969 she had already married Marcial Hernández and given birth to six daughters.

She is the only widow still living.

When he died in the mine, the youngest was only two weeks old.

She “she left the house, but she didn't come back.

I didn't like that he worked there, but there was no other job,” she says.

She had to get by selling food on the streets and with the 20,000 pesos (less than 1,000 euros) that she received in compensation.

Over time, she remarried, with Gilberto Sandoval, a man who was saved that August 31, 69 for a few hours.

She was going to enter the galleries on the next shift.

After the accident, she still worked two more years in the same mine that was the grave of her companions,

Maricela Alfaro, points out the name of Rogelio Ibarra in the monument to the fallen miners in the main square of Barroterán. ANTONIO OJEDA

Rogelio Ibarra was 18 years old and never wanted to be a miner.

He liked to work in the quiet of his ranch.

But he had a one-year-old daughter and another was on the way.

He had to earn his bread.

The first day he went down the mine was March 31, 1969. He never went back up.

He spent time and mourned, his wife remarried and he had another daughter, Marisela Alfaro (50 years old), who now narrates the story.

“My mother said that that day he said goodbye to her as if he already had a feeling.

He hugged her, he was very strange and told her: I'll order the girls.

And that was the last time she saw him.

A thunder was heard so loud and all the people screaming and running, ”she evokes.

The last body came out of the mine a month after the explosion.

The families were given the remains in sealed wooden boxes, they were never able to see their faces again.

It was the beginning of the decline of Barroterán.

During its glory days, the prosperity of coal attracted people from all over the region to work in the galleries.

They opened dozens of stores, a casino, bars, lounges.

Today it looks like a ghost town, a postcard from oblivion where closed businesses reign, houses abandoned years ago half collapsing.

In the town square, there is a golden statue of a mother holding her son, a dead miner, in her arms.

The names of all the victims of the explosion are engraved on a plaque next to the inscription: "Son, you fell doing your duty."

Every March 31 families bring flowers to the place.

subscribe here

to the

newsletter

of EL PAÍS México and receive all the informative keys of the current affairs of this country