The sun sets in the Ceuta neighborhood of Benzú and the sun struggles to prevail over the clouds stuck in the Dead Woman, the mountain above the town of Belyounes, on the Moroccan side of the border.

The backlight casts shadows on a picture of idle neighbors who spend the afternoon in front of the sea, members of the Moroccan auxiliary forces who guard a border crossing that has been officially closed since 2019, and crowded houses that overlook the perimeter fence.

A few hours earlier, in that chiaroscuro, several police units carried out an operation against a human trafficking network that has operated intensely since the summer of 2021. It is the second major raid in Benzú, El Príncipe and other Ceuta neighborhoods, such as Los Rosales and Hadú, so far this year.

More information

The desire to go to Spain remains intact on the other side of the border of Ceuta

The operations are the finishing touch to the return to normalcy of a city that held its breath a year ago now.

Between May 17 and 18, 2021, between 10,000 and 14,500 people entered Ceuta, depending on who the figure is consulted, at a rate of 90 people per minute in the most intense hours of the crisis.

"It is as if half a million people entered Madrid in one day," recalls Juan Jesús Vivas, president of the local Executive.

A year later, Ceuta looks like almost always, waiting for a closed border to reopen in March 2020 and that it will start operating on Tuesday, coinciding with the anniversary of the "hardest and most difficult episode that Ceuta has experienced in its history recently”, according to the president of the autonomous city, from the PP.

Bus line L7 between Constitución and the border between Spain and Morocco in Ceuta. PACO PUENTES

The security forces affirm that the dismantled network has profited from the people who arrived in May and were trapped in Ceuta due to the inability to negotiate an effective return mechanism with Morocco that would continue beyond the first days after the crisis, when some 7,500 people were returned irregularly or returned voluntarily to Morocco.

The massive entry also left more than a thousand children under the tutelage of a municipal administration without spaces or resources to care for them.

"In Ceuta, normality has been recovered in terms of the visibility of people on the streets," says Mabel Deu, local vice president with jurisdiction over minors.

Since the summer of 2021, the exits have been constant, according to police sources.

Also the disappearances and deaths, even of minors.

Those who have not left on their own or after paying up to 4,000 euros to embark on the Peninsula have chosen to apply for asylum.

Between July and October, up to 1,600 applications were formalized in Ceuta, according to the Government Delegation;

in 2020, 285 had been processed (579 in 2019, before the pandemic), according to the Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid (CEAR).

“Many people have left in seedy boats that not even the authorities know about,” says Sabah Ahmed, a businesswoman from Ceuta.

“We know more by word of mouth, when families have called us because a boat has left Ceuta with 20 or 30 people and they have not reached their destination;

and as children, I don't even tell you”.

Ahmed, 61, is in tears as he remembers the incessant phone calls from relatives trying to locate young people who have left for the Peninsula.

According to the volunteers of the aid organization No Name Kitchen, there are still about 30 kids who sleep outdoors because they do not want to enter the devices managed by the SAMU Foundation and which house 166 minors of the 340 protected by the Administration after entering mass of 2021. The Government of the city, with the approval of Madrid,

launched a new process under a Framework Agreement with Morocco to return minors expeditiously.

The procedure did not have legal guarantees and the courts stopped the returns after at least 55 adolescents were sent to Morocco.

Band of the Legion during an act in the center of Ceuta, this Wednesday. PACO PUENTES (EL PAIS)

"We cannot consider the matter settled or the work finished," says President Vivas, "I think that what happened is of such magnitude that there has to be a before and after."

The crisis highlighted a problem that both Ceuta and Melilla have been facing for years: the lack of infrastructure to care for minors and the non-existence of referral mechanisms to other autonomous communities responsible for caring for small migrants who arrive in each territory.

So, 16 communities agreed to receive some 200 minors who were already in Ceuta in 2020. “We have been requesting this for many years, mainly because we start from cities that have a very small area, which have a very high population density.

And much of our territory is not owned by the municipality, but by Defense, for example,

due to our denomination of military places at the time”, explains Deu.

"During the pandemic we had to use the few spaces owned by the municipality to be able to provide this assistance, which was required in this case because we had confinement," he adds.

In 2021, and despite an unsustainable situation, no state-owned space for reception was transferred or enabled and the Temporary Immigrant Stay Center (CETI) only agreed to modify the health protocol and admit asylum seekers after complaints from organizations of human rights.

An unprecedented episode

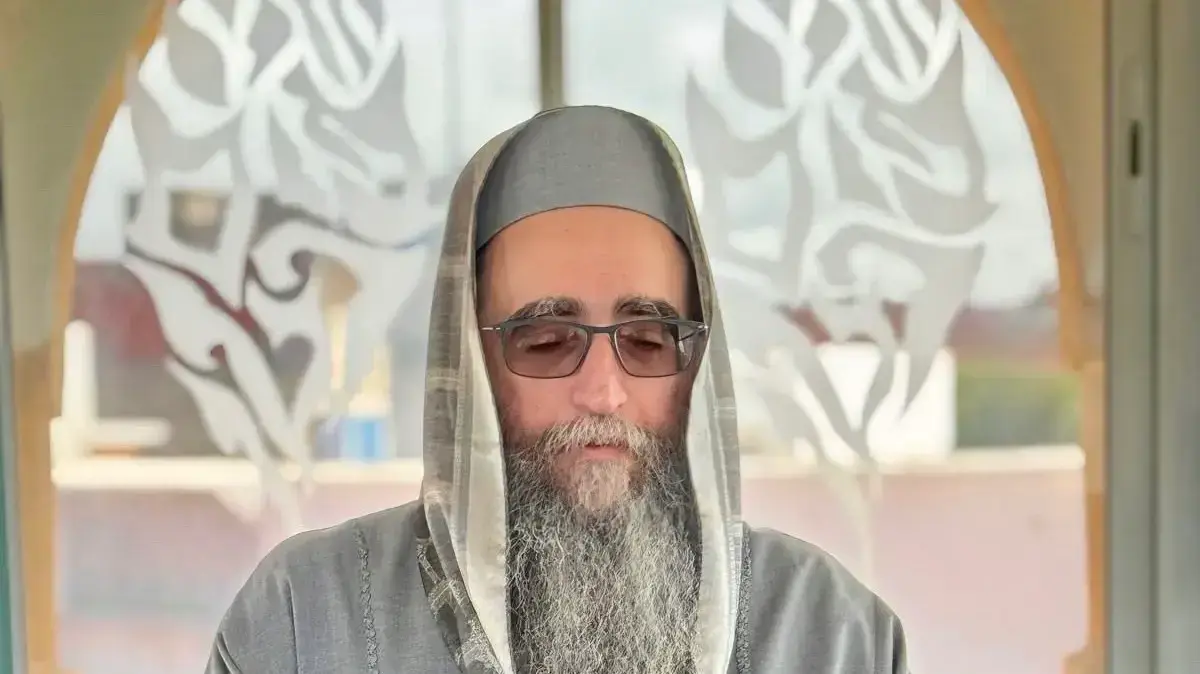

“That specific episode [in May 2021] is unprecedented, it is a historic event,” says Rachid Sbihi, civil guard and leader of the Unified Association of the Civil Guard in Ceuta, “it was an accumulation of people like never before seen before".

"Those of us who were there were overwhelmed until reinforcements came, but that human tide bordering that breakwater and entering Ceuta was practically uncontrollable."

Sbihi was working from early on Monday, first in Benzú, to the north, where the entrance of people, young people, women and even families with children began at dawn, and then in El Tarajal, where at noon the entrance was unstoppable, with thousands of people collapsing the road that leads to Castillejos (Morocco), about seven kilometers from the border with Spain.

Rachid Sbihi, AUGC organization secretary next to the Benzú border in Ceuta. PACO PUENTES

In Ceuta, communication with officers of the Moroccan Army is fluid and constant, but the links are almost personal.

From the breakwaters that announce the international passage of El Tarajal, you can see the bars installed on the Moroccan breakwater that leads to the beach and that prevents access to the sea from land and almost daily raids are carried out with arrests of up to 200 people, mostly Sub-Saharan, around the fence.

Its orography in Ceuta, more abrupt and wooded than in Melilla, hinders surveillance from the Spanish side.

As a priority and necessary partner for migratory control, the pulse of Morocco has increased misgivings about the Rabat commitment.

The comings and goings in the negotiations for the reopening of the border after two years of traumatic closure on both sides have given rise to a strange heavy hope in businessmen, merchants, workers and families who have lived in suspense.

Only after Madrid reversed its position on Western Sahara and supported Rabat's autonomy plan for the former Spanish colony was the dialogue reactivated.

A week earlier, on March 2, up to 2,500 people staged the largest attempt to jump over the Melilla fence in the city's history.

“We want and desire good relations with our neighbors, but these good relations must be based on respect,

Beyond the collapse of services in a city that confined itself during the first hours of uncertainty and in the midst of restrictions and social distancing in the face of the health emergency, the crisis brought to the surface an old fear: Morocco's threat to sovereignty Spanish from Ceuta and Melilla, always answered.

"There was no fear, there was panic, because we didn't know what was going to happen, but above all because we didn't know if these people came because they needed help or why," says Alex Castillo, a 28-year-old waiter who runs a cafeteria downtown from the city.

Border of Benzú in Ceuta, between Spain and Morocco. PACO PUENTES

The extreme right has tried to extract a political profit from that fear that has strained to the limit the essential coexistence in a city where half of its 85,000 inhabitants identify themselves as Muslims.

"What happened in May has revealed certain issues and if someone still doubted it, I think that Ceuta needs a State pact," says Vivas, whose minority government of the PP has chosen to rely on the PSOE councilors to isolate Vox.

Its leader, Santiago Abascal, was named

persona non grata

by the Assembly after planting himself in Ceuta and accusing politicians and neighbors with an Arab name of being “fifth columnists” and “pro-Moroccans”.

"You have to fight fear," Vivas settles.

"Fear is our main enemy."

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/GFCQJEKMHZC55D6YJGKO3V2MRI.jpg)