Enlarge image

Photo: Karl-Josef Hildenbrand / dpa

It must belong to the German essence.

When the International Monetary Fund IMF or leading research institutes in Germany announce that the economy is weakening and that there will be tens of thousands fewer jobs in the country, the excitement will be limited.

Even new numbers on the rapid extinction of species do not seem to lead to any major emotional boosts.

But woe if the reported inflation rate is higher in Germany for a few months - even if there are apparently temporary factors behind it.

Then many heads turn red, eager kitchen commentators downgrade all those economists to scoundrels who don't panic.

Facts don't seem so important anymore.

What is true: inflation hits precisely those people who do not have that much money.

What is less understandable, however, is the tendency of one or the other doom prophet to see the new age of inflation approaching now.

Oh, the end of the currency.

Or to ponder that that's the way it is now, if you want to save the climate.

Fight one problem with another?

Doesn't sound optimal now either.

The question is whether such price hikes are really as good for the climate as they are now - and whether we simply need inflation to preserve our species.

And therefore it would also be bad to prevent drastic price increases or to offset them with state money, as the expert Veronika Grimm has just spent in contradiction to corresponding attempts in Spain and Italy.

Too bitterly beautiful to be true

It is correct that a significant part of the inflation is currently coming from higher energy prices - whether through the new CO₂ tax on fuels and heating since January (without energy, inflation should be just over two percent this year, no drama); or by sharply rising prices for oil, gas and coal, as well as the CO₂ price in general, as determined by supply and demand in the European trading system. In the technocratic model world of commercially available economic interpreters, all of this should mean that people then also need less (fossil) energy - good for the climate.

Too bitterly beautiful to be true? What speaks against the fairytale miracle effect of such inflation is that experience has shown that it is important for the conversion of the economy to be able to calculate with steadily rising prices on CO₂ emissions - in order to strategically convert production and products.

What is currently happening in the markets is roughly the opposite of steady. The price of a barrel of oil has doubled in a year. Since the middle of August alone, the prices for energy on the raw material markets have risen by a third. Crazy. This cannot be explained with fundamentally real reasons. It is highly likely that this is not only due to the much-cited corona-related bottlenecks in delivery (which in itself is only temporary). But to a significant extent speculation, as the Parisian economist and financial market specialist Véronique Riches-Flores says. There are crazy herd instincts, and one or the other uses a trend to speculate richly.

Real movements in supply and demand also do not explain why CO₂ prices in European emissions trading have tripled since Corona spring 2020. Curiosity: Since then, industrial lobbies have been rumbling against dangerously rising costs, which otherwise always swear by free-market climate protection. That's the way it is with the market. This is how it is when markets with virtual values trade in uncertainty. There is then speculation on political events.

The dilemma: such price jumps make a plannable conversion of the economy difficult.

Worse still: when financial markets drive prices up so high and there are herd instincts behind them, with every further high the probability increases that the rally (in stock exchange terms) will end just as abruptly, the trend then overturns - and prices collapse.

Just like it happens every few years.

Then a crisis XY is enough - the oil price drops to 30 dollars again.

Nice for consumers.

Not so nice for everyone who tries to save the climate through high energy prices.

The phenomenon of the corona economy

At the moment, the global phenomenon seems to be behind a number of price spikes: in the still-corona times, a lot is already being bought in some places, but there is still a lockdown in other places - and production is therefore not keeping up. If that is true, everything indicates that this acute price driver will also cease to have an abrupt effect when the crisis is finally over. Even if that can take a while. Speculation also plays a role here: The prices for industrial raw materials have been falling for weeks at a similarly rapid pace as they had previously soared.

In any case, it is not so certain whether the fight against climate change will have to lead to more inflation in the long term. There are estimates that inflation to save the planet could turn out to be half a percentage point higher than it is now. However, recent studies by Beatrice Weder di Mauro speak against such an effect. The Geneva economist evaluated a number of cases in which governments in Europe and Canada raised CO₂ taxes over the past three decades - and checked whether inflation occurred afterwards. And lo and behold: the rate of inflation was generally not higher - rather, it was actually lower.

What seems astonishing can possibly be resolved. On the one hand, high CO₂ taxes are not an end in themselves, but should instead lead to people buying or making low-carbon things that are correspondingly cheaper. When buying a car, for example, the alternative of an electric vehicle is still more expensive. However, it is already foreseeable that prices will fall with rising sales and higher production. Renewable energies are cheaper in the long run anyway. So there is no need to fear inflation.

On the other hand, according to Weder di Mauro, a less pleasant phenomenon seems to have worked in the investigated cases of rising CO₂ taxes: the higher costs initially led to people having less real income and being able to consume - which in purely economic terms is accordingly less demand in the economy and ultimately less inflation. Thus, higher energy prices went hand in hand with lower prices for other goods and services. On balance, the effect of higher CO₂ taxes was often rather deflationary, according to the economist. Also not good.

This is exactly where the biggest problem lies: A cost-for-climate logic may sound great in theory, but it is difficult to maintain in real-political practice.

All you have to do is let the current German nagging take effect.

You don't even want to know how the "Bild" newspaper and other inflation and doom apologists rage when CO₂ taxes really rise.

Just like the CO₂ prices for industry.

You can try to compensate politically with the most beautiful compensations - in practice a populist will always intervene.

Compensating is not trivial either.

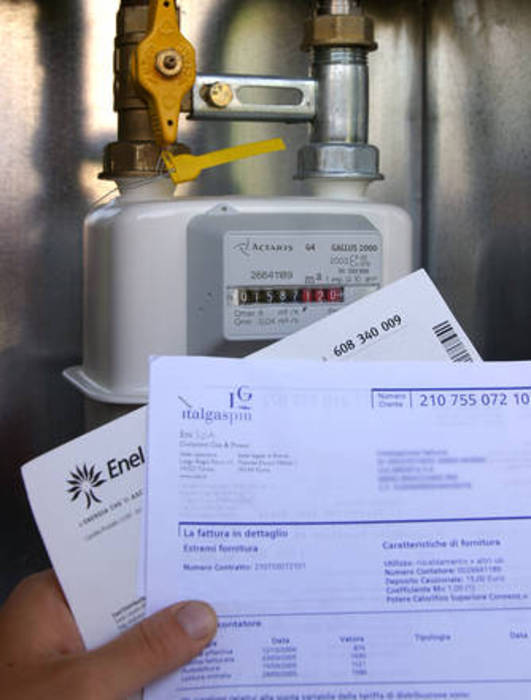

Especially since the prices at the petrol pump are so much more visible and noticeable than, say, a plus or minus in the EEG surcharge, which is drowned out in the jumble of numbers on the electricity bill.

This is going to be tedious.

And time is running out.

The nagging of these weeks tends to confirm the doubts as to whether the high CO₂ prices as the »central lead instrument« (Grimm's business practice) are such a good idea at all. The Chouchou idea of the traditional economy threatens to fail sooner or later due to the political and social reality. The lofty appeal that the Spaniards and Italians should not provide for a cushioning of the price rises by decree and subsidy is also pointless. Otherwise, the French experienced with the yellow vest protests. That set France's climate policy back years.

It makes sense and is politically feasible to gradually make everything that threatens to exacerbate the climate crisis more expensive.

Relying on speculative heights on the energy markets or nicely thought-out climate inflation for drivers and residents could ultimately do more harm than good.

More positive incentives and public investments are needed.

Other topic.

Sequel follows.