I remember well the first time I heard it. At a friend's house who had a record player. "This sounds like Gould to me," I said. "No, no," he replied, "Gould is the one who sounds like her." At the time I did not care, but as I listened more to Gould I frequently returned to Rosalyn Tureck's Bach. As Paul Elie recounted in

Reinventing Bach,

Gould first heard the pianist live at the age of sixteen. Tureck was touring Canada at the end of 1948 and in January 1949 he played the third suite of the

Little Organ Book

at a luxury department store in downtown Toronto.

and some transcriptions of two corals made by herself.

Gould described the concert as a revelation, although in fact he had been obsessively listening to the pianist's records for some time.

Thanks to those recordings, "he said," he felt less alone in his battle for a transparent and pure Bach.

He knew other pianists (Landowska, Hess), but Tureck's technique was something else, with its clear articulation, its

tempi

, its dynamics, its precise ornaments "and a sense of peace" —he would later say— “that had nothing to do with it. with languor, but with moral rectitude in the liturgical sense ”.

Gould was prone to religious bombast, but as much as they called it

As "High Priestess of Bach," Tureck was much colder spiritually. Gould's fervor was dramatic, excessive, almost parodic; Tureck's devotion was cerebral and restrained, and therefore more severe. Like Gould, Tureck was also a great communicator, but not prone to eccentric antics (see on the web how serious she explains the relationship between a Bach fugue and Schönberg's twelve-tone). The pianist also seemed absent when she played, transported to another dimension, but she didn't make any fuss. He experienced a decisive trance in his life, but as far as I know, he did not describe it as divine enlightenment, but as an Alice adventure. He was playing a prelude and fugue of the

well-tempered harpsichord

(in A minor, Book I, BWV 865) when she suddenly grasped the deep structure and technique needed to reveal it: “I lost my sense of consciousness and myself. For a moment I ceased to exist and came back after an interval that, I thought, had lasted twenty minutes but was actually barely twenty seconds ”. When he touched on the exposition of the fugue to his teacher, Mrs. Samaroff, she congratulated him, but told him that it was impossible to maintain that technique during the entire execution of a work. Tureck ignored and decided to perfect his technique: “I had entered through a small door into a vast and luminous territory without limit, green, fertile […] I could no longer go back to the known world […] so I went through that small door and I never went back ”.

His analytical approach, Elie points out, replaced the slow, romantic prewar Bach with a more agile and clean-lined one.

His contrapuntal style was described as mechanical, like that of a pianola, but Tureck knew what he was doing.

Few pianists, ”Benjamin Ivry said.

they played Bach "with such deliberate phrasing, as if he were trying to get certain notes to go straight through the listeners' skulls into their brains."

Tureck knew the historical treatises on interpretation that guide the interpreters of early music, but their execution was based more on the structuring "of harmonic, contrapuntal and rhythmic relationships" that the composer had designed.

Seen like this, it is not unusual that in the summer of that same 1949 he took Schönberg lessons in California, and paid them at almost 200 dollars, much more than any other student of that exile.

Tureck greatly admired the composer and planned to record the

Piano Pieces

op.

11 and op.

19, but never did.

More information

Glenn Gould Variations

Anatomy of a recording

To all this: Tureck was born in Chicago in 1913 into a family of Russian Jewish immigrants. Her grandfather was a famous singer from Kiev (who toured in carriages drawn by eight white horses) and her parents encouraged her to play the piano from a very young age. He studied with Jan Chiapusso, a Javanese-born half-Dutch half-Italian pianist who discovered gamelan for him and encouraged him to dedicate himself to Bach. Another teacher of hers, Shopia Brillant-Liven, changed her life when she took her to a Léon Theremin concert and was fascinated by that otherworldly sound that - she will say later -

"It was much more abstract than any electric keyboard."

At the age of sixteen he went to New York to study with Olga Samaroff-Stokowski at the Juilliard School and in the entrance exam he played Bach's 48 preludes and fugues by heart.

He then obtained a scholarship to study electronic instruments and his debut at Carnegie Hall in 1932 was not with a piano, but with a theremin.

American pianist Rosalyn Tureck (1914 - 2003) in concert with the Philharmonia Orchestra, 28th January 1958. (Photo by Erich Auerbach / Getty Images) Erich Auerbach / Getty Images

Devoting herself to Bach didn't seem like the best way for a virtuous young woman to build a career, but Tureck ignored those conventions and, while she was showing off with Rachmaninov or Liszt, she focused entirely on Bach.

In 1935 it was said that he was too cerebral and lacking in emotion, but in 1937 he began to give concerts where he played the

Goldberg Variations in

full

.

At first the music critic also described it as intellectual and distant, or even as a typical product of a mechanical age, something that she always denied (fidelity to the

form

of a work, ”she said,“ does not exclude different options for performance. In 1944, the critics fell asleep after he played the

Goldbergs

three times

: "the pianist" - it was said in

The

Times—

"He gives each variation such a specific character, with such verve and vitality, that the listener has the impression of hearing Bach himself play them on the harpsichord". In November 1947 (shortly before Gould heard her in Canada) she left the Tom Hall audience in New York speechless by playing the third of the

English Suites

and some preludes and fugues of

The Well-Tempered Clavier.

Tureck also played the harpsichord, and was familiar with Bach's historical approaches, but was interested in the abstract Bach that electronics allowed. For her, Benjamin Ivry also said, it is “the composition of the music, and not the instrument on which it is played, that gives authenticity to a Bach performance”.

As Elie also points out, his sobriety was not something alien to the spirit of the times and resembles the “stylized severity of Beckett or Giacometti, a reduction of the work to its skeletal essence”. Tureck, it must be remembered, did more for contemporary music than is believed: he defended the electronic instruments of innovators like Robert Moog (who gave him one of his synthesizers) and for twenty years he developed an electronic piano with Hugo Benioff. He founded

Composer Today

,

an association that tried to put interpreters and creators in contact, thanks to which some work by Messiaen was premiered in New York, or electronic music by Vladimir Ussachevsky. In 1952 Tureck gave the first concert in the United States with tape and electronic music.

Tureck loved to interact with scientists, such as Otto Loewi, Nobel and precursor of neurobiology, the Nobel Prize in chemistry Florenz Michaels, or the biophysicist Isidor Isaac Rabi, another Nobel who - as Ivry recalled - in addition to discussing magnetic resonance imaging with her. taught to play the 20-prong musical comb. Tureck also got to know Mandelbrot and was interested in the relationship of fractals to music, but in the 1990s she protested vigorously against some analyzes that, according to her, had “nothing to do with Bach's processes of thought and composition. ”. He dealt with the philosopher Ernest Nagel, with whom he discussed a lot about philosophy, "although he did not at all accept the ideas of his group, led by Carnap." He also treated the famous Isaiah Berlin, with whom he maintained a great friendship; he loved the critic

Lionell Trilling and treated his high school classmate Saul Bellow his whole life. She had as a friend a unique, exceptional poet, Elizabeth Bishop, who in 1947 invited Robert Lowell to attend the Town Hall concert to hear "the best Bach interpreter there is." Bishop loaned his key to Tureck, and before a trip — very much hers — gave him a compass.

Tureck spent part of his life in Europe perhaps because there was a more devoted audience for Bach. He moved to London in 1957 and created an instrumental group. In 1966 he founded the

International Bach Society

and the

Tureck Bach Institute

and two years later the

Institute of Bach Studies

. In 1977 he celebrated his temporary return to New York with a concert in which he played the

Goldbergs

twice, on harpsichord and piano. She was a great lecturer and taught at the Philadelphia Conservatory, the Juilliard, Columbia and Maryland Universities, and various Oxford colleges. She was the first woman to conduct the New York Philharmonic and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. In 1998 he recorded the

Goldberg

for the DG label, which later recovered its first version, that of 1953 (detailed lists of his discography are collected in Elie's book).

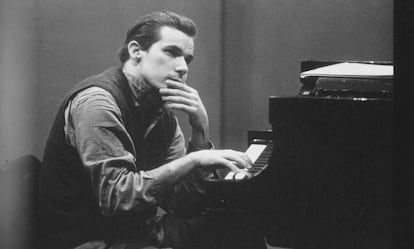

The pianist Glenn Gould.

I suppose the Gould apostles could find reasons to be angry with Tureck. Although the Canadian praised her, in the late nineties Tureck declared that he considered him a talented and brilliant pianist "but his idiosyncrasies were the result of a desperate desire to be noticed" and that - he stated - "is totally unacceptable: idiosyncratic interpretation is not it has nothing to do with art ”. “It took a lot from me. When I listen to his records, I hear myself playing myself, because I was the only one in the world who made these ornaments, ”she said as well. Someone recalls “hearing Gould, in his early twenties, demonstrate why his interpretation of Bach was superior to that of the recording made by 'one of the best Bach interpreters of the time'.Was it Tureck? Are we not facing a case of symbolic murder of the mother? Tureck had a reputation for being strict, and his irony could be scathing. When Gould died of a brain hemorrhage at age fifty, he declared that it did not surprise him so much, "considering how tense his playing was ...". She could have said something a little kinder about a failed but world-famous pianist, faster than she, yes, but fascinated by the same world that was revealed to Tureck through a small door. She could have been a little more loving, though it's true: sometimes Gould took everything to the extreme. That is why it is not surprising that, when you cannot keep up with their rhythm and you need something more serene, in the end you always end up going back to Tureck.When Gould died of a brain hemorrhage at age fifty, he declared that it did not surprise him so much, "considering how tense his playing was ...". She could have said something a little kinder about a failed but world-famous pianist, faster than she, yes, but fascinated by the same world that was revealed to Tureck through a small door. She could have been a little more loving, though it's true: sometimes Gould took everything to the extreme. That is why it is not surprising that, when you cannot keep up with their rhythm and you need something more serene, in the end you always end up going back to Tureck.When Gould died of a brain hemorrhage at age fifty, he declared that it did not surprise him so much, "considering how tense his playing was ...". She could have said something a little kinder about a failed but world-famous pianist, faster than she, yes, but fascinated by the same world that was revealed to Tureck through a small door. She could have been a little more loving, though it's true: sometimes Gould took everything to the extreme. That is why it is not surprising that, when you cannot keep up with their rhythm and you need something more serene, in the end you always end up going back to Tureck.but fascinated by the same world that Tureck revealed through a small door. She could have been a little more loving, though it's true: sometimes Gould took everything to the extreme. That is why it is not surprising that, when you cannot keep up with their rhythm and you need something more serene, in the end you always end up going back to Tureck.but fascinated by the same world that Tureck revealed through a small door. She could have been a little more loving, though it's true: sometimes Gould took everything to the extreme. That is why it is not surprising that, when you cannot keep up with their rhythm and you need something more serene, in the end you always end up going back to Tureck.

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.