Michèle Dawson Haber

09/17/2021 18:51

Clarín.com

The New York Times International Weekly

Updated 9/17/2021 6:51 PM

The first time I heard my father's voice, he had died 53 years ago.

It all started when my cousin, who lives in Jerusalem, gave me 25 audio reels in round metal cans.

He had found them there while cleaning his parents' house.

"They belong to your father singing opera," my cousin told me on one of my infrequent visits to Israel.

“I also found his scores, negatives, and photos.

You and your sister should have them. "

After my father died in Canada in 1965, his family held onto their remaining possessions;

attachment avoided having to give it up completely.

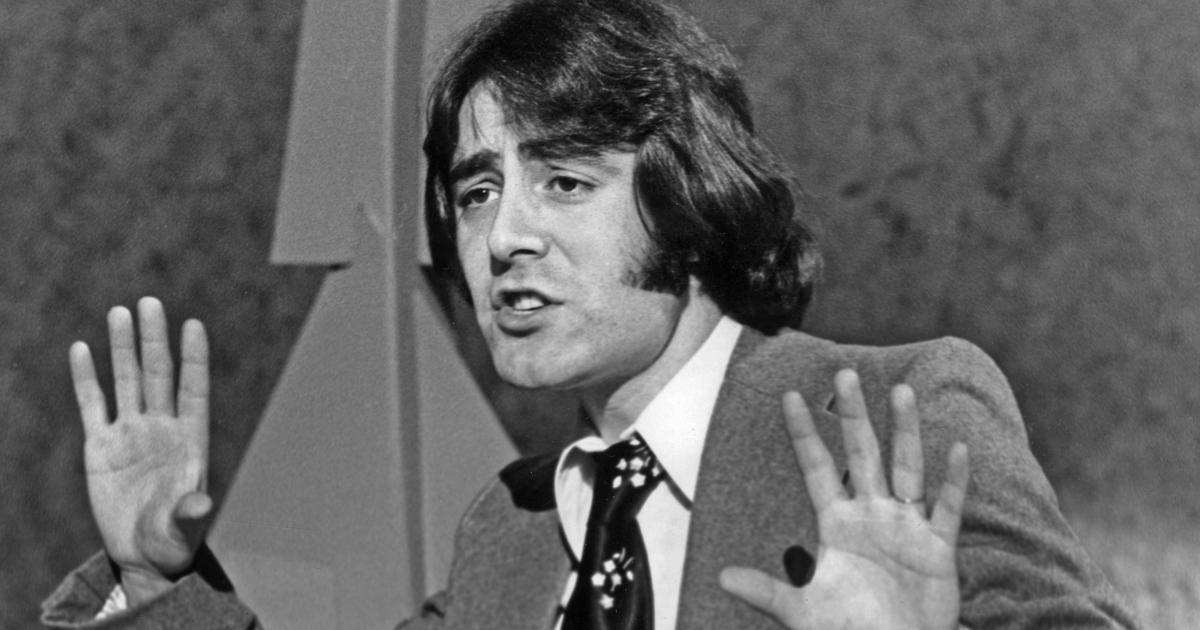

"Look at this picture of him," my cousin said, snapping a photo of a lanky young man with deep eyes, bushy eyebrows, and a hesitant smile.

"Who does he look like?".

"I guess he looks a bit like me," I said, feeling uncomfortable.

My father had

committed suicide

when I was 3 months old and, unlike my older sister, Ruth, I felt

little attached

to him.

"More than a little!" She said.

“You have the same shy smile.

Can't you see it?

"A little," I replied.

After returning to Toronto with my father's belongings, I sent them all to Ruth, who was then living in another country.

I didn't think about the photo of the young man again.

"It's more your father than mine," I said to explain why I didn't have anything.

Two years after our father's suicide, our mother married another struggling artist, this time a poet.

But there their similarities ended.

Our stepfather

adopted

Ruth and me, legally erasing our last names.

Growing up, we never consider it important.

We didn't feel adopted.

The "real" adoptees, we ignorantly assumed, were children who had been placed with other families due to desperate circumstances.

Two more children were born and our new family of six came together and looked to the future.

Our mother had made a

clean slate

, trying to overwrite our old life with new memories.

However, there was still a feeling of otherness that bound us to Ruth and me.

Ruth was haunted by her inability to remember our father and haunted by wanting to know more about him.

Our mother refused to speak, always answering my teenage sister's questions with tears and procrastination.

"Another day," he would say, or "when you're older."

Dejected and crying, Ruth came to me.

From an early age I took on the role of my sister's comforter.

Even after we grew up and lived in different countries, she called whenever her feelings of loss arose, and I listened and comforted her.

She never had to worry about reciprocating;

I did not have a similar longing.

There was no room for my loss, so I

assumed it didn't exist.

Three years ago, Ruth found a sound engineer who digitized our father's 25 reels of audio.

I was curious, but I was also concerned that Ruth would be disappointed by its content.

As I listened, he sent me regular updates on WhatsApp.

Most of the recordings were of him playing the piano and singing in various languages.

One day Ruth called me on

Skype

while I was at work.

I was in a room with the sound engineer.

"You have to hear this now," he told me.

"It's really amazing".

I closed my office door and Ruth played me a tape that had been recorded in 1963.

Ruth was 3 years old, and she and our father were looking at pictures together.

The voices were so clear that it was as if they were in the room with me.

"Who is it?

Is it daddy? ”He said.

"No!" Ruth said.

"Is it mom?"

"No!".

"Is it Ruthie?"

"Me!".

We heard him laugh with delight and then there was a wet, mouth-on-skin sound vibrating, as if he were blowing his belly, followed by an explosion of laughter.

My father's laugh was high and energetic, but his voice was lower, a mellifluous, accented baritone.

Hearing his voice, my indifference vanished.

Until that moment, I didn't know what my father sounded like.

I had gone my whole life without realizing that I didn't know.

Ruth and the sound man were staring at me on the Skype screen, waiting for my reaction.

I didn't want to collapse in front of them.

"Well?" Ruth said.

"Wow," I said.

"Go that?".

"Wow, that's something important."

Realizing that she was not ready to speak, she filled the silence with her reactions of joy and amazement.

I made an excuse that I had to go back to work and hung up.

In my office,

I cried alone

, first out of anger because he abandoned us, and then out of long-repressed longing.

I had seen photos of my father and heard some stories, but none of this brought him closer to me.

However, the man I listened to, so intimate and close, was my father!

Hearing him speak and laugh brought my soul out of a deep slumber, and it was both terrifying and invigorating.

There would be no going back.

He needed to know more.

Now I became the obsessed daughter, looking everywhere for him.

I read the hundreds of letters to and from him that my mother had kept in a cardboard box.

They described a sensitive man who was always striving to get ahead.

In the letters my parents wrote to each other, the struggles of their

tumultuous marriage

were exposed

.

My next step was to locate and interview elderly friends and family who remembered a kind and noble man who liked to sing country songs from his mother's balcony in Jerusalem.

Then, even though I knew it would be painful to read it, I spent a year fighting for the right to see the

police report

detailing the lurid details of its last moments.

How incongruous it is to feel gratitude for all those things, and yet I did, as the gaps in my family's timeline were filled.

I found out more about my parents than most adult children ever know.

Still, I wasn't satisfied and couldn't explain why to anyone, not even my sister.

What else do you hope to find?

”Ruth asked me.

"Actually, I don't know, maybe a photo," I said and choked, realizing how much I wanted exactly that.

"Just a picture of him hugging me, so I can stop."

I came into my father's life at the worst possible time, when his life was falling apart, so it was no wonder there were no photos of me.

However, that little hope was all I had, so I begged Ruth to scan the thousands of our father's negatives from his years as an amateur photographer.

Months later he texted me with a crying face emoticon.

"I've scanned them all and you don't show up," he wrote.

"Sorry".

There was nothing left to discover.

He had followed all the clues, read all the letters, and studied all the memories.

I should have been glad I learned so many things, but instead

I felt empty.

One day, after telling a friend about my efforts, she told me about a psychologist she had interviewed for her podcast.

“Listen to it.

I think it will be useful to you, ”he told me.

While exercising in my basement the next day, I listened to it, feeling skeptical about the relevance of what

Michael Grand

called “the constellation of adoption.

Sure, being adopted by my stepfather made me a stepdaughter, so what?

As if it were an answer, Grand explained that many stepchildren face the same existential doubts as traditional adoptees, the ones I had thought were different from me.

"Without information about his origins, the adoptee has a

deficient narrative

: he is missing chapter one of his life," he said.

Not only had I been looking for my father, I realized then: I had also been looking for myself.

The next Grand Point stopped me midway, and I fell to my knees, tears streaming down my face.

The key is in

importance, he

explained.

The adopted person wants to know what is important.

There was.

Despite my inquiries and the extraordinary amount of written, sound, and photographic artifacts I had unearthed, I had never found, and would never find, any proof that I existed in my father's world.

That

I mattered.

It was time to stop looking.

I didn't know if he cared about me, and I never would, but what I realized is that he matters to me.

I am no longer a spectator of loss, I found my father, and that is nothing.

I have learned enough to fill my first chapter of life and, although it will remain incomplete, I can insert myself into the history of my family, intertwined in the stories of my parents and my sister.

And I can decide to wear my shy smile with pride, grateful to have something that he gave only to me.

Michèle Dawson Haber lives in Toronto and is writing a memoir on family secrets, identity, and adoption.

c.2021 The New York Times Company

Look also

Modern Love: Why My Daughter Married (Temporarily) At 13

Modern Love: The Lace Underwear I've Never Worn