We are since '89

all articles

SPIEGEL: Mr. Heise, your movie "Heimat ist ein Raum aus Zeit" was originally scheduled for release on October 3, but now it starts one week earlier. Was the holiday too state-supporting as the start date?

Thomas Heise: I did not want the movie to have its theatrical release in the fall, because that's too close for me on the 3rd of October and people are so upset that the topic "turnaround" is hanging over their heads. Especially since the festivities are mainly focused on the fall of the Berlin Wall.

SPIEGEL: Is that a problem?

Heise: Decisive was not 30 years ago the beautiful and necessary, equally ambivalent moment of the fall of the Berlin Wall, but the fact that long before a people no longer wanted to shit, declared itself sovereign to his government, went on the road, to announce what it thought. In one half of Germany mind you.

SPIEGEL: Now it's autumn, and your film looks like a final commentary on the current home debate.

Heise: You have to get back a concept like home. I already had the debate in my film "Fatherland": I was also asked why that's the name. But why should I leave such a term to anyone? When I use it, it is mine, neither right nor contaminated.

SPIEGEL: In "Heimat" you read from letters and records of your family - such as your mother's diary entries after the bombing of Dresden and show documents - including the lists of deported Viennese Jews, which included their great-grandparents on the maternal side. How did these documents come together?

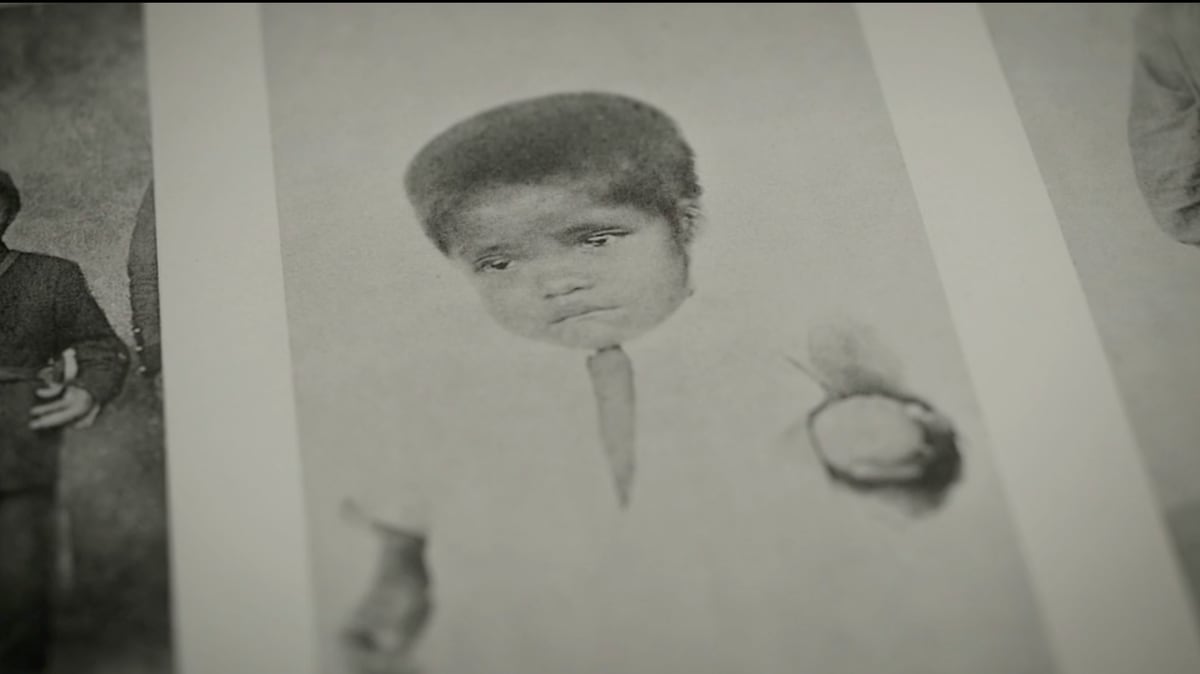

Heise: I found the first letters as a child: They were stowed in a box under a chest of drawers, under which I crawled while hiding. The brown wrapping paper with the writing on it fascinated me even then. I did not understand what that was until much later: These were the letters my father and brother wrote to their parents when they were interned in a forced labor camp for "Jewish half-breeds" in 1944. I deciphered and transcribed the letters with a magnifying glass because they were already decaying. Since then, these credentials have occupied me.

SPIEGEL: Her grandfather Wilhelm Heise was a Germanist and educator who was banned by the Nazis and later became professor of pedagogy in the GDR. Her parents Rosemarie and Wolfgang Heise were well-known intellectuals in the GDR. Heiner Müller called her father the "probably only East German philosopher who did not deserve to sink into the current staging of forgetting." When did you get the feeling that your family could tell you something about German history?

Heise: At some point I noticed that certain structures are repeated in the generations: All of this family, for example, have made noise with the superiors - no matter in which regime. It has always popped, there was in principle an opposition exists. When my mother died in 2014 and a year later my brother, I found that now no one is there. Then I knew that I have to make something of it now.

SPIEGEL: In one part of the film you read in detail from the love letters your mother wrote to Udo, a man from the West with whom she had an affair in front of her father ....

Heise: ... I am so glad that I found Udo. Without him "home" would probably have become a movie that would again run under the catching slogan "East", so not relevant to the whole.

SPIEGEL: In your production, Udo becomes the personification of the early FRG: a boastful, loud man who urges your mother to move in with him to the west - after all, the first home payment has already been made.

Heise: The story between Udo and my mother shows how conditions developed at that time: It is the first great love of the two, but it is a crashing political ruin, because they can not do together in all willing. Udo came from a sinister Nazi who was involved in the killing of capitulation-willing soldiers in Upper Silesia. For Udo, a whole new era actually started after the war. My mother, on the other hand, came from a socialist household. I actually wanted to tell its story, but that would have really blown up the frame.

SPIEGEL: The timelessness of your pictures is a special quality; your films barely age, even though you are picking up historically precisely identifiable constellations, such as the fall of the Berlin Wall. How did you come to this kind of filming?

Heise: That probably stems from the fact that I do not really belong to either the East or the West. That was already the case in the GDR. Although I studied at the Babelsberg film school, but I knew early that none of my films would be shown at the time. After my exmatriculation, I thought about doing my films on the question of what will interest people in 300 or 400 years - what I can tell them about my presence. But that had something to do with despair. There was little else left for me to do than to imagine what some of them cut into faces when they see my films one day. This impulse has remained. And the way movie culture is shaped in Germany, that does not make me so clear.

SPIEGEL: What bothers you in particular?

Heise: The dependence on television, of course, but also the non-respect of the local film history. If you look in other countries, what is offered on markets not only in the store, but also on the roadside pirated, then you will find there just as many old and new films. In Germany, there are the old films, except for sometimes bad exceptions, not even legal. "The woman of my dreams" for example. Even my older films like "Barluschke" are hardly available. Now I put the films that I have digital into the net - regardless of whether I have the rights or not.

SPIEGEL: You finally stopped studying in 1982. How did you experience the time afterwards?

Heise: Difficult. I was a day laborer, then I first made radio, but even there, all my work was not completed or released. Even a feature with Erwin Geschonneck ( editor's note: one of the most famous actors of the GDR ) about his time in the Dachau concentration camp was only sent in late 1989. Some years after my exmatriculation, however, I became a master student of Gerhard Scheumann at the Academy of Arts of the GDR, which was more of a social measure, taught by Heiner Müller. So I was out of the first line of fire, but I had at the same time still running for ten years "Operational process" "school" on the neck.

SPIEGEL: That means the Stasi was prepared for you. What was the goal of the "process"?

Heise: I should not be able to do anything that would somehow harm the GDR, whatever that was. But I also knew that I did not want to work in the West. I was not interested in the kind of three-day fame that some from the GDR experienced in the West. And I did not want to go to the West anyway, the FRG was no alternative for me.

SPIEGEL: In "Material" you are filming a woman admonishing on a demo on November 8, 1989: If we do not reform the GDR now, we'll probably never get another chance. Do you regret this missed opportunity?

Heise: Absolutely. But I do not grieve, I note. If the wall had not worked, perhaps a week later actual reformists would have been elected to the Politburo or Central Committee. But that had to be prevented. The Central Committee of the SED prevented a real reunification through the opening of the Berlin Wall, that is, one that had something to do with both parts of Germany and that would have moved more in West Germany. That ended the revolution.

SPIEGEL: So you continue to argue with history?

Heise: In the Heiner Müller play "The Lohndrücker" an old comrade is asked: "What has been, can you bury that?" His answer: "No." I like that. Götz Aly does this in the Berliner Zeitung, for example, when he writes about the 8th of May: Every year he admonishes the Chancellor again because she does not take the Russians part in the celebration of the liberation. They, with their 20 million deaths, seem to be of no importance. But somehow also clear, if all elites in this country consist of West Germans: They have no experience with Russians who know the most still of the CDU posters from the fifties. And the ignorance among my students is also immense.

SPIEGEL: How does that show?

Heise: You have no idea. In the absolute majority, they know nothing about the importance of the Soviet Army during the Second World War, of its 20 million dead. Stalingrad is a sole problem for freezing German soldiers, and the Soviet side plays virtually no role other than being something to defend against. And when we watch Tarkowski films, they only know the films that were made after his departure from the Soviet Union. The former things they do not take in hindsight, true. This reminds me of our relationship with prisons and the behavior of prisoners.

SPIEGEL: What do you mean by that?

Heise: When you're in jail, you really want to look out, want to hear something from the world, you're very attentive to seeing others. But who looks at the prison from outside to see something else? Our present East-West relationship has a lot to do with this circumstance: the overwhelming, majority disinterest of the West in the East, in all countries there and in its history, including that of the GDR, must finally change. This means above all ideas and cultural history.

"Home is a space of time" celebrates its official Berlin premiere on October 1 at the Deutsches Theater. The Akademie der Künste Berlin shows "Material" on October 5 and "Heimat ist ein Raum aus Zeit". Afterwards talks with Thomas Heise take place.