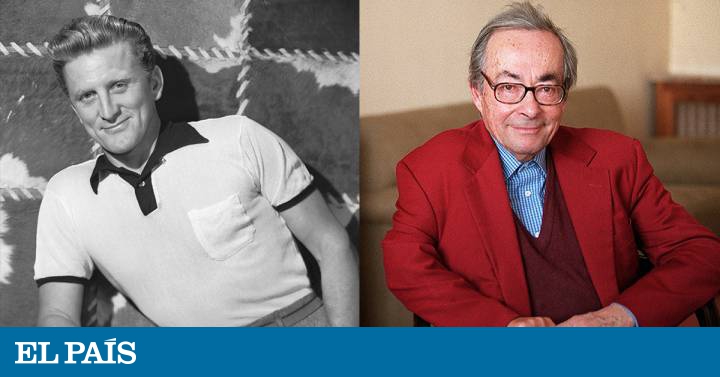

When last week the thinker George Steiner died at age 90 and actor Kirk Douglas (Issur Danielovitch) at 103, I felt that with them two of the last representatives of a generation of Euro-Atlantic intellectuals and artists died, marked by some of the more bloody episodes of the twentieth century, such as the Holocaust and ideological stigmatization during the Cold War.

They had very different childhoods, but both came from Central European migrant families of Jewish origin and, although they managed to position themselves within the Anglo-Saxon cultural establishment, they always maintained a certain condition of outsiderism. If Douglas described himself as “the ragman's son” in The Ragman's Son (1988), his first autobiography, and explained the material difficulties in which he grew up in the New York municipality of Amsterdam; Steiner always recognized the well-off and scholarly character his childhood had despite the fact that his family had to flee from Nazism, first from Vienna to Paris and from there to New York.

While the boy Issy (diminutive of Issur) sold sweets to help support his home, little George learned to read classical Greek with his father. When he could, Issy ran out of his Jewish environment. His family, who spoke Yiddish at home, did not see with bad eyes that he was trained as a rabbi, given his aptitudes at school. But Issy already knew that he wanted to be an actor. He adopted an Anglo-Saxon name, managed to enter the university and, later, in the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York thanks to his talent, energy and determination, demonstrating, once again, that the American dream was possible.

Steiner never hid his Hebrew identity, rather the opposite. He suffered in some way from the survivor syndrome. Of the numerous Jewish classmates of the high school he attended in the French capital, it seems, only he and another child survived. Why precisely him? He wondered. He devoted part of his intellectual life to understanding how Shoah could be possible within an enlightened culture such as European and, specifically, German. This followed the line drawn by Benjamin, Adorno and other continental thinkers, Jews like him, although he did not necessarily reach the same critical conclusions. His faith in the superiority and universalism of the European enlightened project remained intact.

Steiner devoted himself in the mid-1970s with After Babel, an inquiry into the "exact art" of translation. He was a freak in a British academy that at that time felt oblivious to his philosophical interest in the Holocaust and was not recognized in the continental hermeneutical tradition. Douglas then had more than 60 movies behind him. Among them, The winner (1949) and The madman with red hair (1956), who not only consecrated him as a star, but as an independent and bold mind in the most conventional golden Hollywood. His autonomy became a legend when he managed to break McCarthy's blacklist by openly collaborating with screenwriter Dalton Trumbo in Spartacus (1960).

Douglas and Steiner were extraordinarily prolific and versatile men, as well as vain. Steiner considered himself a transmitter: the rabbi Douglas did not want to be. It influenced the difference between this role and that of the creator or artist. Douglas complied with the prototype of the latter: intense, physical, seductive, generous, possessed of an extraordinary joie de vivre ; He could become a true cretin, as he himself admitted. Towards the end of his life, he embraced Judaism and turned, his relatives say, a more affable and compassionate person. It is likely that actors like him paved the way for a later Hollywoodense generation that not only recognized their Jewish identity, but also took pride and inspiration. Douglas never won an Oscar as an actor, something that has been attributed to his refusal to align with anti-communism.

Steiner, on the other hand, left the United States, where he had been trained, and remained in the United Kingdom with one foot in Switzerland. He obeyed the will of his father, who considered that not returning to Europe was a victory for Hitler, who predicted that there would be no one left with a Jewish name there. The British academy always maintained a certain skepticism towards its neo-Renaissance. Some accused him of wanting to embrace too much knowledge without due depth. Be that as it may, the studies of the Holocaust have long been a discipline in British universities.

Both reached the dawn of a new era in which both male hegemony and Eurocentric thinking are in question. Douglas is likely to be pursued by the same shadow of doubt as many of his Hollywood companions regarding his behavior with women. Steiner recognized in his posthumous interview that he failed to gauge the importance of feminism and the questioning of reason illustrated. It is worth wondering how this generation would flourish, historical for its talent and its exceptional circumstances, if it was born in this century.

Olivia Muñoz-Rojas has a PhD in Sociology from the London School of Economics.