A masterpiece is always a great misunderstanding. Because it has survived the era in which it was done, it seems to us that it represents and summarizes it: but in its time that work might be invisible, or that its rarity, the exceptionalness that we now admire, will condemn it to marginality or failure. Don Quijote represents for us the Spanish literature of the first decades of the seventeenth century, but in reality it looks very little like any other book that was published at that time, and no one, perhaps or its author, who however took so much pride If he had written it, he considered it an example of high literature. The executions of Goya are our image of the War of Independence: but that painting, like May 2 , left no trace of public resonance when it was painted in 1814, and during the following years it remained hidden in the stores, as if no one had noticed him.

The masterpiece is an exception, not the illustration of a standard. It belongs fully to its time, which crystallizes in it as in a mirror of extraordinary sharpness, but it is also alien and peripheral. In 1656, in Spain, nobody painted anything that looked far from Las Meninas . The masterpiece is both contemporary and extemporaneous. It is contemporary because nobody can achieve something original and true if they do not work with the materials of their immediate experience of the world; It is extemporaneous because it naturally moves away from the planned and established, not because of a mania of originality, but because what it has to express has not been said or shown yet.

The masterpiece was sometimes rejected in its time not because it seemed very new, but because in the eyes contaminated by fashion it seemed dated. In every age there are things that seem anachronistic, but not because they are anchored in the past, but because they belong to the future: the cities walked, the bicycles, the trams, were suddenly anachronistic in the fifties and sixties, in a tyrannically dictated modernity by car manufacturers and oil companies. There are always powers interested in imposing a single form of present. People are afraid to stay out of our time, or go against the tide, and that is why we accept attitudes and values, even words, so dictated by the subtle and omnipresent coercion of fashion.

For us, any of the great portraits or self-portraits of Rembrandt's maturity represents the golden age of Dutch painting in the middle of the 17th century. That broad and free brushstroke, those rich fillings, those backgrounds of grayness and darkness, those expressions of selfish sorrow, or of lonely irony, that air so often of nobility and collapse: Rembrandt challenges us with a closeness greater than that of other painters of his time, not because his sensibility anticipates ours, but because his influence, through the romantics and the Impressionists, is at the origin of our way of looking. In the catalog of the masters of modernity that Baudelaire establishes in his poem Los faros , Rembrandt is, together with Goya, one of the most powerful luminaries. Rembrandt is in Van Gogh, in Soutine, in Rouault, in the Germans of the twenties and thirties, in Lucian Freud.

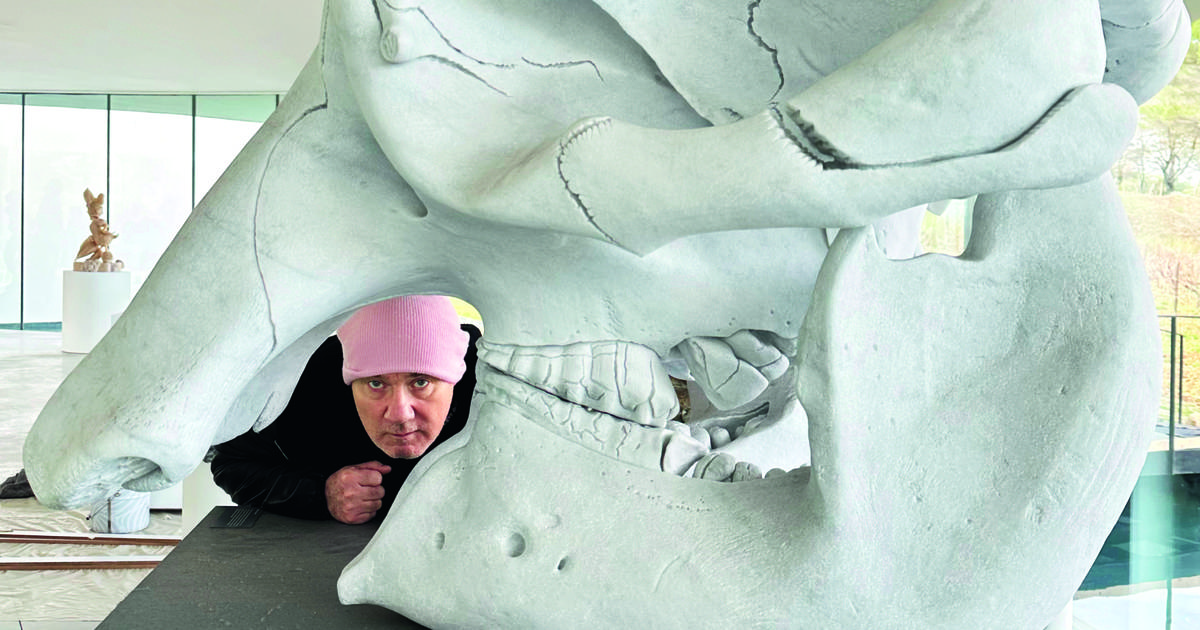

Where he is not is in his contemporaries in the last period of his life. If the exhibition that has just opened at the Thyssen Museum were only of Rembrandt's portraits we would not learn so much about it. The solitude of his masterpieces would once again strengthen the misunderstanding. We would see Rembrandt isolated in his singularity, canonized in the mixture of genius. Lacking terms of comparison we would appear as a solitary giant, against a vague empty background. Now, surrounded by others, or rather mixed with them, as it was in the tumultuous reality of Amsterdam, included in the tradition to which it belonged and in the aesthetic and commercial system in which he worked his career, we can better appreciate how much Rembrandt had contemporary and how much of extemporaneous.

There is an arrogant tendency to co-opt the best artists of the past to make them similar to us, worthy predecessors of a superiority that only we possess. But Rembrandt is a man of his time, not ours. Rembrandt painted for wealthy clients in Amsterdam whom he knew, not for modern art theorists several centuries later. In the thirties and forties of the seventeenth century, in a country of thrilling commercial and cultural energy, Rembrandt achieved worldly success by painting portraits of bourgeois who he looked very much like in the thrust of his social escalation, in a kind of balance Quiet between the exhibition of opulence and the desire to live and the Puritan reserve. In the dreary southern Catholic Europe any trace of dedication to trade or some form of productive economy was an indelible stain of shame. In Amsterdam, painters portrayed merchants, beer makers, wealthy owners of mills or navigation companies. Rembrandt invested and speculated like them, and dressed equally sumptuously.

Then the misfortune came, and the time that had been his left him behind. Rembrandt did not depend on the Court, like Velázquez, or on religious orders, like almost all other Spanish painters; but of the market, and therefore of the hazards of supply and demand, and changes in fashion. By 1650 his way of painting had become obsolete. Painters younger than him, in some cases former disciples of his, imposed a new style in the portrait, more expansive in shapes and colors, more scenographic, close to the courtly painting of England and France, in brighter shades, more suitable for highlight the new luxury of dresses and interiors now visibly aristocratic. When the era demanded greater clarities, Rembrandt's palette became darker, and his figures more unfinished, more sullenly confined in themselves. Old, wounded by misfortune, postponed, Rembrandt worked at the same time his ruin and his future glory. In his last self-portraits it is like a crumbling statue of himself. He would not have been so much a painter of the future if his contemporaries had not seemed like a painter of the past.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/NUZJBZKFJJC3TORYXB6GF6WOEA.jpg)