Emergency literature has as bad a reputation as fast food. There are, however, authors who, throughout history, have skipped the prescription of waiting for emotions to cool before sitting down to write. These days, next to the most urgent Decameron , it has become a common place to relate Daniel Defoe's Diary of the Year of the Plague with the coronavirus, but the word diary confuses: between the appearance of the narrative (1722) and the supposed narrated events (occurred in 1665) had passed more than half a century. Defoe himself had used in 1719 that Alexander Selkrik neglect suffered between 1704 and 1708 in a Chilean island to write the foundational work of modern English novel Robinson Crusoe.

The 20th century skipped all deadlines, but some results were worth it. Thus, the Civil War produced masterpieces to the sprint, such as the tales of A blood and fire (1937), by Manuel Chaves Nogales, or the poems of Spain, this chalice (1939), from César Vallejo, printed on “paper of the poor ”(made of rags) at the Montserrat Abbey during the war. Few, however, reacted as quickly to an event as Leonardo Sciascia. The Red Brigades kidnapped the president of the Christian Democracy in March 1978, assassinated him in May, and he wrote the 200 pages of his anthology The Moro Case three months later. Also Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio, whose essays work was born mostly from reading the newspapers, used the Challenger accident of January 1986 to finish off his reflections on progress in As long as the gods do not change, nothing will have changed , published in the autumn of that year. same year.

The 21st century is a separate case. According to the bibliographic record Books in Print, in the five-year period that followed the attacks of September 11, 2001, more than a thousand non-fiction titles on that event and nearly 30 novels were published, some of them signed by Don Delillo ( El jump man ), John Updike ( Terrorist ) or Jonathan Safran Foer ( So strong, so close ). Three years later, the attacks of March 11 in Madrid had -with Luis Mateo Díez, Blanca Riestra or Adolfo García Ortega- their own local novelistic echo.

If in 2008 the misfortune of many in the form of crisis restored the prestige of social literature -with Rafael Chirbes, Pablo Gutiérrez or Cristina Fallarás-, in 2014 the role was for only one man: Dominique Strauss-Kahn, who had resigned as president of the IMF before the continuous demands for sexual harassment. In 2016 Le Figaro counted the books on the case: half a hundred came out. For its part, the Notre-Dame fire of a year ago quickly burst into the work of authors as different as Ken Follett and Elizabeth Duval.

In Spain, the monographic quota of novelties was occupied by the Catalan independence process until the Covid-19 closed publishers and bookstores. It is not too risky to imagine that world confinement will produce an avalanche of titles to fill various stories of literature. Not counting what they have been writing in Asia for months or with express reissues such as the Pandemic: virus and fear -from the Argentinean Mónica Müller in Paidós-, the early Europeans have already arrived. Paolo Giordano published last week in digital edition and in Spanish and Catalan In times of contagion / In contagion (Salamandra / Edicions 62). The book by the author of The Solitude of Prime, physicist and novelist numbers, has the added value derived from one of the countries most affected by the pandemic: Italy. It mixes personal testimony - a last dinner with friends who minimize what is coming - with reflections on the immediate future. “When I was in secondary school,” he says, “there were several protests against globalization. I only participated once, and I was very disappointed because I didn't understand what exactly our complaint was: everything was too abstract, too generic. In fact, I even liked globalization: it promised good music and fantastic trips. Even today, the word globalization disorients me as imprecise and protean, but I guess its contours by its side effects. For example, a pandemic. For example, this new shared responsibility from which no one can escape. ”

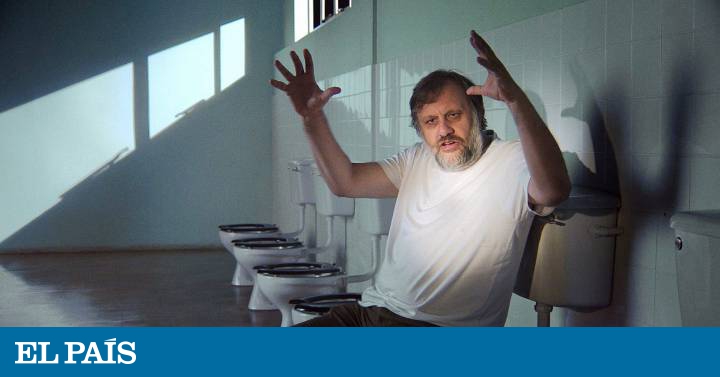

Another of the sprinters has been the electric Slavoj Zizek, who has just released Pandemic (OR Books) in English, an essay whose copyright has been transferred to Doctors without Borders. In his hundred pages, the Slovenian philosopher raises the possibility that imagining the end of capitalism is no longer more difficult than imagining the end of the world. Covid-19 can succeed where Marx, Lenin and liberation theologians failed. In his opinion, the dilemma is: either a reinvented communism or barbarism. "I am not utopian, I do not appeal to solidarity between peoples," he writes. On the contrary, I believe that the current crisis shows that solidarity and cooperation respond to the survival instinct of each one, and that it is the only rational and selfish response that exists. Not just for the coronavirus. "

In the absence of the bookstores reopening and we are attending the launch of the great novel about the coronavirus, the Internet has been filled with testimonies from writers who narrate their confinement. In Portugal, Gonçalo Tavares does it daily on the Expresso pages while in France, Leila Slimani does the same on the Le Monde pages and Marie Darrieussecq on the Le Point pages. The friendly nature of its entries has produced a storm of reproaches and parodies to the point of qualifying the first - Goncourt award in 2016 for Sweet Song - of “Maria Antonieta del confinamiento”. Criticism does not quarantine.

For its part, the Society section of EL PAÍS publishes daily an author's chronicle on the confinement -from Soledad Puértolas to Luis Landero through María Fernanda Ampuero- in addition to the series Vieja, amortizada y en casa , by Maruja Torres. Meanwhile, the Culture section houses the Berlanguian novel by installments by Antonio Orejudo La casa de los Peláez . In Babelia , meanwhile, you can read the reflections of, among others, Richard Ford, Yan Lianke, Antonio Muñoz Molina or Siri Hustvedt. Like plague, syphilis or AIDS, the coronavirus will one day be a literary genre. And hopefully nothing more than that.