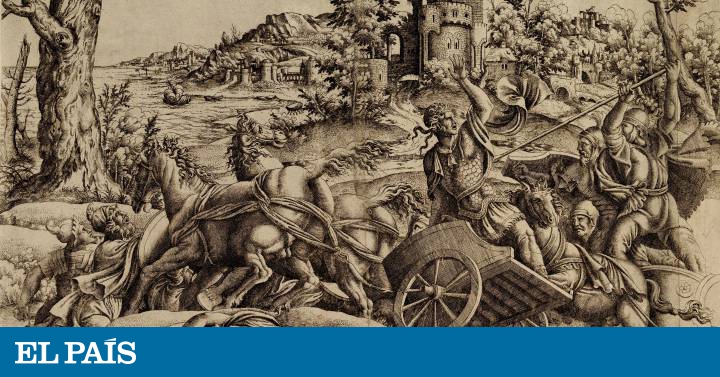

After unearthing the citadel of Troy, whose real existence had been diluted in the mists of myth, and after photographing his wife Sophia with the so-called Helen jewels, the Prussian Heinrich Schliemann, expeditious businessman and amateur archaeologist , set out for Mycenae with the Greece Description of Pausanias under his arm. His intention there was to unearth not only the city of the conquerors of Troy, but the very figure of King Agamemnon, the lord of warriors who had led the most famous war in myth and literature. Both Aeschylus in his tragedy Agamemnon and Homer in the OdysseyWe are told that it was in Mycenae that the king found death at the hands of his wife Clytemnestra and his lover "like an ox tied to a manger", while trying to dress in clothes whose sleeves were sewn. For his part, the indefatigable traveler Pausanias had indicated the exact place where tradition affirmed that his grave and that of his murderers were found; Sufficient indications for Schliemann to conquer glory again. If the Prussian really believed that Agamemnon had had a real existence outside the mythical dimension, it does not matter, because the fact is that from that new archaeological campaign Agamemnon arose from the land of myth with something that no other protagonist of the Trojan legend has ever possessed: one side. Schliemann brought to light what researcher Cathy Gere defines in her book The Tomb of Agamemnon (Profile Books, 2006) as "the human face of the Homeric epic."

There are timeless stories in which legend and reality seem to communicate through secret passageways. This occurs in effect with the myth of Troy, whose narrative power continues to ignite the flame of new creations; An example is the recent appearance of the graphic novel La cholera , by Santiago García and Javier Olivares (Astiberri, 2020), which includes powerful images of the Iliad , or the brilliant musical approach to the Odyssey that Vinicio Capossela carried out almost a year ago. decade - what is a decade compared to the almost 3000 years of the Trojan legend? - in his album Marinai, profeti e balene . It also occurs with the legend of the founding of Rome by Romulus and Remus, a semi-legendary episode that was transmitted to us by ancient authors such as Titus Livius and Plutarch, and which has been recreated in Matteo Rovere's film Il primo re (2019), shot in an archaic Latin scientifically reconstructed by philologists for the occasion. And it occurs with a historical event of enormous magnitude and significance, such as the destruction of Pompeii, whose streets can now be traveled imagining what life would be like in that Roman city before Vesuvius erupted, which is the proposal that the book A day in Pompeii (Espasa, 2020) by Fernando Lillo offers us.

The specific mention of these three chapters of Antiquity is due to the fact that in recent times several news stories have followed one another in the media that attract the gaze of a wide audience towards these ancient stories: the exhibition that the British Museum exhibited until the beginning of March, precisely on the reality and myth of Troy, is one; another is the discovery in the Roman Forum of a chamber with a possible tuff sarcophagus that some headlines hinted, in the wake of the best clickbaits , that it could be that of the mythical Romulus; and another, the announcement that a skull found more than a century ago in the Neapolitan town Castellammare di Stabia could belong to the writer Pliny the Elder, witness and victim of the Vesuvian eruption. But the interest of the media and the large-scale dissemination of the archaeological findings to the public is certainly not new and in Schliemann's case it led him to become part of the legend when he telegraphed to the press what would today be a formidable cyber-hook : "I have seen the face of Agamemnon."

The phrase is apocryphal (Cathy Gere gives us that the original formulation was: "This body is very similar to the image that I formed long ago in my imagination of the powerful Agamemnon"), but the news of the discovery immediately spread throughout Europe between an audience eager to see the face of a Homer hero. At the end of November 1876, he found in a circle of tombs the body of three men of heroic proportions: one of them was totally decomposed, the other two had their faces covered in gold-carved death masks. When Schliemann raised one of them his skull immediately turned to dust, but when he raised the other, two eyes and "32 beautiful teeth" looked at him: the face of the conqueror of Troy. It is here that Schliemann performed the definitive hand trick: the magnificent mortuary plate that today bears the name of Mask of Agamemnon was not the one that covered that face with brand-new teeth in which the archaeologist had recognized the face of the lord of warriors, but the one with the skull that fell apart under his gaze.

In honor of justice, Agamemnon should have received another face, one with puffed cheeks and very thick lips, in which the human face of the Homeric epic displayed a rougher and less regal face. Nor does it matter that the discovered bodies belonged to Mycenaean nobles some four centuries prior to the estimated time for a hypothetical Trojan war - around 1200 BC - because Schliemann won all the honors and recognitions, and an editorial in The Times newspaper London of December 18, 1876 greeted the discovery thus: "The great king of men who found a bard in Homer exhibits his royal condition again before the world by the work of Dr. Schliemann." Today visitors to the National Archaeological Museum of Athens are clustered before "the Mona Lisa of prehistory" (again, the quote is from Cathy Gere) as if they truly contemplated the face of King Agamemnon, oblivious to the fact that the death mask is different. , had he looked more like a Prussian prince, today he would lend his features to the lord of Mycenae.

Schliemann died in Naples in 1890, some ten years before someone unearthed seventy-three bodies in a town south of Pompeii; one of them, richly decked out, could be that of Gaius Pliny Secundus, known to literature as Pliny the Elder. That was at least the hypothesis of the engineer Gennaro Matrone, the owner of the land where the discovery occurred; a hypothesis that in his case was rejected by the press and the academic world, which led him to bury the rest of the bones, preserving only the skull and jaw that he believed to be Pliny's. As time went by, both ended up exhibited, along with examples of malformations and kidney and liver stones, in the Flajani room of the Museo Storico Nazionale Dell'Arte Sanitaria in Rome, where for a time they appeared under the banner of “Skull of Pliny the Elder ”, An announcement that was later nuanced:“ Skull from the excavations of Pompeii and attributed to Pliny ”. However, at the end of last January the conclusions of the Pliny Project, started in 2017 (about a century and two decades after the discovery), which ratified the belonging of the skull (not the jaw) to the Roman writer, were presented. Conclusion to which specialists such as Mary Beard, the prestigious Cambridge classicist and author of works such as Pompeii: history and legend of a Roman city (Critique, 2014), think that it is wrong. For his part, the director of the project, Andrea Cionci, found an echo in the prestigious newspaper La Stampa to underline that the truth is that there is no indication that denies that the skull belongs to the great character. Perhaps the definitive word, as in the case of the Mask of Agamemnon, is found by the public who comes to the showcase to contemplate the skull, ignoring the small print on the label, to have before their eyes a small streak of one night in the history, that of the eruption of Vesuvius, with proportions of legend and in which Pliny the Elder acquired traces not of a hero of the myth, but of a very human one.

We know Pliny the Elder from the two letters - both collected in the small volume The eruption of Vesuvius (Edhasa, 2019) - that his nephew Pliny the Younger sent to the historian Tacitus at the latter's request that he write the details of the death of his uncle in the catastrophe of Vesuvius, and we also know him for his only preserved work, a kind of encyclopedia of nature in 37 books entitled Natural History . So, if it is not certain that his skull has reached us, we can be glad that through these works we can enjoy part of his heart and brain.

Regarding his brain: modern scholars have not generally been generous in evaluating his style and the scientific validity of his Naturalis Historia (in Spanish, for example, Cátedra presents a good edition of books devoted to animals and the pharmacopoeia related to them), but Italo Calvino in his classic Why read the classics? (Siruela) recommends his continued reading for his admiration for the phenomena that surround us and for his heated praise and defense of nature, as well as for the ethical will of his work. And with respect to his heart: his nephew tells us how Pliny the Elder, who was in Cape Miseno in command of the fleet of which he was an admiral, decided to set sail in a small boat carried by his curiosity as a naturalist - this is the starting point of the recommended manga series Plinius , by Mari Yamazaki and Tori Miki (Ponent Mon, 2017) - to closely observe the prodigious column of smoke that emerged from a mountain, when a call for help arrived. It was then that he changed his plans and took out his quadriremes towards the first known civil protection mission. And it was in a night of panic in which his nephew assures that “there were those who, for fear of death, asked for death, and many begged the help of the gods while other more numerous did not believe that there were any gods left anywhere and that that night would be eternal and the last in the universe ”when Pliny the Elder found death in Stabias by suffocation. Pliny died saving lives in a fight against something new, dark and unknown. A different kind of hero than the epic king of Mycenae.

As a curiosity, let's say that the rescuers had protected their heads from the rain from the rock debris that fell by means of cushions fastened by straps, thus the controversial skull, at least in principle, and even without supporters of the likes of Schliemann. , it has some remote option of being the one that contained the brain of Pliny.

Óscar Martínez is a Greek teacher, translator of La Iliada (Editorial Alliance), author of Heroes who look into the eyes of the gods (Edaf) and president of the Madrid delegation of the Spanish Society for Classical Studies.