On a sidewalk, a man holds an artifact that resembles a large stethoscope. The toe of his shoe looks up, indicating some impatience. Dressed in a military uniform, in the same way that a doctor listens to the heartbeat of his patient, very concentrated he hopes to hear through the headphones the sounds picked up by a detector positioned on the floor. Under the title Disposition pratique des appareils pour l'ecoute terrestre ("Practical arrangement of devices for terrestrial listening") the photograph was taken between 1917 and 1918 by the former National Office for Scientific and Industrial Research and Inventions (today CNRS) as part of its policy to stimulate innovation during the early 20th century.

MORE INFORMATION

PHOTO GALLERY Warfare inventions for mass consumption

Photography invites humor and absurdity, since the place chosen for listening does not agree with the use of an instrument designed to locate landmines. It is part of the book Inventions 1918-1935 , which published by RVB Books brings together “what is I could call the prehistory of the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) ”, as Luce Lebart, its author, explains. (The exhibition organized under the same title can be seen next fall at the MAST Foundation in Bologna).

Between 1915 and 1938 hundreds of photographs and films were produced in France in order to stimulate scientific and industrial advances. This series of images, mostly unknown, compose a story intertwined by design where science meets technology and industry. They document two decades of innovation, initially aimed at national defense, to later adapt to the different facets of domestic life. Inventions often appear centered on a neutral background, viewed from the front or from the side, as in police photos. Sometimes the inventor himself appears, or a human figure manipulating the invention.

"Five years ago, I started a study for the preservation of glass plates found in the CNRS archives," says Lebart. "I was surprised that these images were totally unknown given their aesthetic power and also their humorous tone as documents of social history, design and consumption." As her investigation continued, the author encountered the figure of Jules-Louis Breton. Politician and inventor (credited with inventions such as a prototype armored tank and a washing machine), he was at the head of the ORNI in 1915. Passionate about cinema, he will systematize its use as well as that of photography at the service of inventions since 1917. "Its purpose was to generate an archive —although they were national secrets, they were not accessible to the public— that would serve to lighten the much-hated bureaucratic procedures, making sure that any idea was paired with a scientist or producer before seeing the light", the author explains.

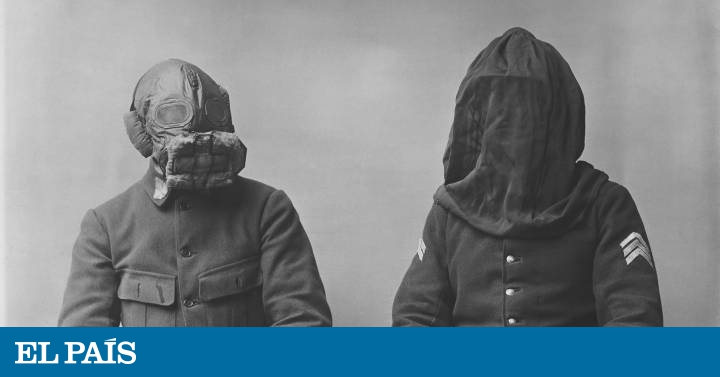

Despite the utilitarian purposes of images and, in principle, lacking any artistic ambition, they are aesthetically surprising and reveal the talent of those visionaries and pioneers who within these institutions experimented with the power of the static and moving image. "I was struck by its link with Surrealism and sometimes its closeness to the New German Vision, since they are prior to the avant-gardes. I was also interested in their banality, the beauty of everyday objects. I felt like an archaeologist exhuming the remains from the beginning of our consumer society. Like the image of an archaic washing machine. At the beginning of the 20th century it was not common to photograph these types of household items. Karl Blossfeldt photographed plants, August Sander photographed people, however this collection focuses on objects of war and the objects that came later. We went from the gas mask to the washing machine. "Thus the collection establishes a connection between the objects of the consumer society and the war. It is through the contrast of two of the images where is best seen this relationship that leads us from the tragedy of the war to consumerism and mass production: one of them shows a man with a sweeping brush, another, taken an tees of war, shows a man holding a gun. They are separated by 20 years but the same iconographic resource is used to show the sweeping brush as the rifle used in the war. Objects appear in the center and those who hold them pose similarly. "That surprised me," says Lebart. Set an evolution from war to peace through items. It is from the First World War when a dynamic for mass production is created. Today it is worth remembering how in France a general mobilization was established at the beginning of the war and the Higher Commission for the Examination of Inventions was created for the benefit of national defense. As a result, among other things, the production of different types of masks increased.

In these images intended to illustrate the effectiveness of the object, a poetic linked both to its manifest aesthetic power and to the more comical side that appears when they incorporate the human figure stands out.

"They reflect a burlesque comic military aesthetic that reveals that behind them hides a film director as imaginative and original as Alfred Machin," says Lebart. The images do not bear a signature, only the inventor's name appears. But it was an image of a man posing in a studio that led the author to reveal the authorship of the filmmaker. Author of the prophetic and pacifist Maudite soit la guerre , released on the eve of the First World War, Machin was hired by Breton to produce the images. “In many of them you can see how he puts into practice all the keys of his cinematographic imagination: he gets very close in the shots, as if he were using a zoom. In the way in which she makes people pose - as an example in the images in which she teaches us how to drink with a mask - the gesture is emphasized, which links her to silent films. This is where the comic touch came from, which gave the whole a very intriguing air and manifests its freedom to circumvent the codes of photographic objectivity. Unlike silent movies, photography had seldom been intended to make people laugh. I was struck by the image of a soldier posing on all fours to demonstrate how to carry a rifle. Machin had been a buslesque specialist , and also spent time filming wild animals in Africa. ”

The file resembles a large visual laboratory notebook where the stages of the creation of the different inventions are detailed. “What moved me the most was the relationship between invention and failure; how research progresses through trial and error, "concludes Lebart. “Nothing happens immediately. Many processes require the participation of many people, step by step. And it is something that I intend to make clear in the book. Trial and error could lead to useless objects, or in the same way generate something that decades later stands out as something clearly remarkable. I think that both scientists and artists are very aware of this. We are always trying, failing, starting again without letting ourselves be overcome by discouragement. Innovation is related to failure and Breton knew it ”. 'Try again. It fails again. Fail better, 'wrote Samuel Beckett.

Inventions 1915-1938. Luce Lebart. RVB Books. 304 pages. 39 euros.