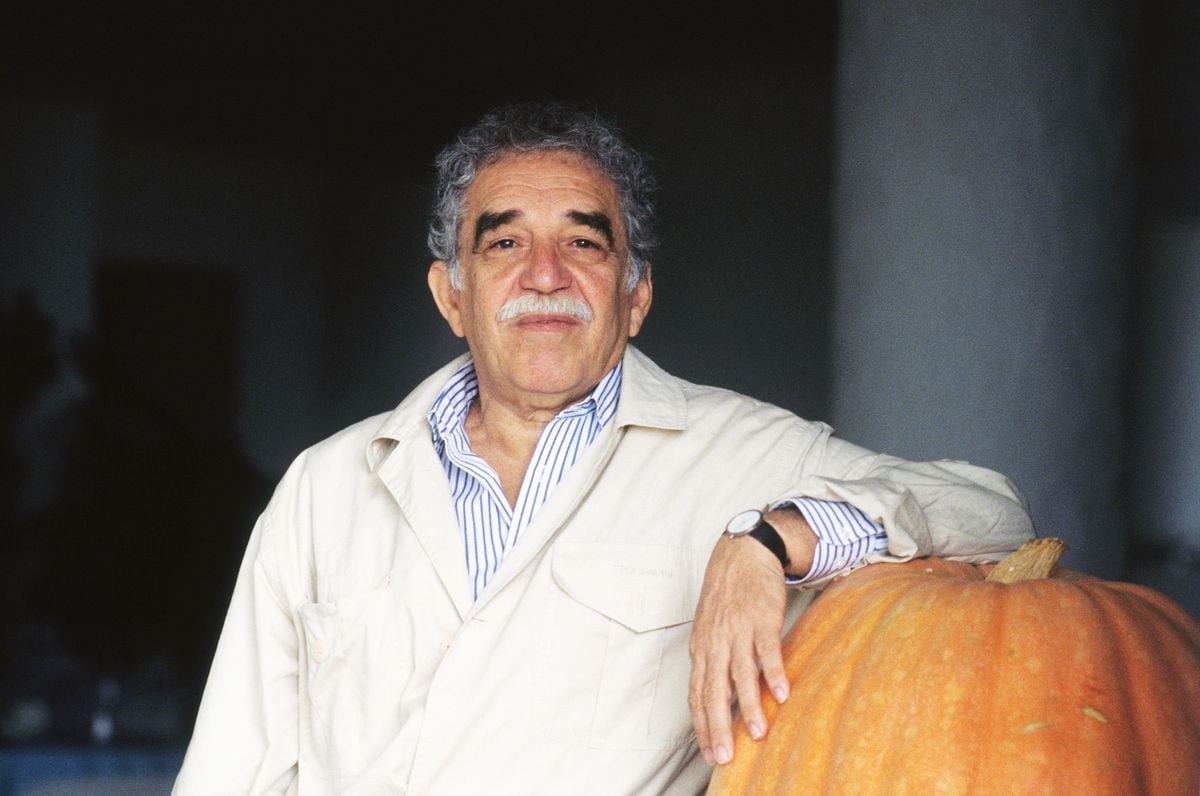

When, at the age of nine, the teacher asked Eligio Gabriel García Márquez (Colombia, 1947-2001) if when he grew up he would want to be a writer like his brother, the boy replied: "No, because I don't like to lie" . Eligio was baptized Gabriel because the García Márquez's father wanted that duplicity in his family, but over the years, until 2001, when Eligio died in Bogotá, that descendant who also bore the Nobel name did everything possible to that neither that patronymic nor the immediate kinship was known in public.

So Eligio, who did end up telling lies because he is the author of some novels and was an important journalist in his country, signed Eligio García and that is how he introduced himself to the interviewees (he did large literary interviews, such as those contained in Son asi. Latin American writers , La Oveja Negra publishing house, 1982; El Áncora Editores, 2002) and in this way he went on to the history of journalism and the literature of this language.

- Photogallery: Gabo's family and friends

- One hundred times Gabo

In fact, the report that he included in that book about the private and public figure of his brother the Nobel Prize appeared in the press without any signature, and only the identity of the author was revealed for the publication of that volume that is now read, in many aspects, like a novelty about a phenomenon that he lived closely with without more stridency than what his work could unleash.

His friend Gustavo Tatis, a writer who followed his life and his work to the end and who wrote an already famous book about Gabo and his family, The Conjurer's Yellow Flower (Navona 2019), told this week from Colombia: “Eligio fought to be he did not want to live off the fame of his older brother; In some cases, such as Vargas Llosa, with whom he was in Caracas when Gabo was given Rómulo Gallegos, he could not hide it, but before others, such as Guillermo Cabrera Infante or Alejo Carpentier, he presented himself as Eligio García, and as Eligio García signed then those reports ”.

In the book, which is now a rarity about the boom seen from within when he is left alone, in Vargas Llosa, a survivor of the explosion, Eligio narrates the strange situation created with the author of Consecration of Spring . Then Carpentier was at the unpleasant peak of fame, he granted Eligio an interview that was never held, due to various indispositions of the Cuban genius. And so Eligio García went on a pilgrimage, especially in Paris, without the report taking place, until, in that city, things seemed to be straightening out. False alarm, because again this man much more sullen than his literature slammed the door, although he wanted to give him a signed book. "What is your name?". Eligio told him his own name, and Carpentier asked him for more detail. Until he ended up telling her both his last names. "And why didn't you tell me before ?!" "He never told anyone," says Tatis.

It was, Tatis continues, "of an impressive simplicity." And he adds: “He helped young writers to feel close to Gabo, he studied Physics so as not to approach literature, or perhaps to get closer to Sábato, who was his friend [and is one of the great portraits in the book], and ended up writing one of the key books on his brother's writing, Tras las keys de Melquíades, as well as The Third Death of Santiago Nasar , about the novel that Gabo set in Sucre, Eligio's birthplace ”.

His passion for journalism, "like North Americans", is present above all in the text that he dedicates to his brother in Caracas, on that occasion of Rómulo Gallegos. Possessed by that aspiration for totality that the contemporaries of Norman Mailer or Truman Capote had, and Gabriel García Márquez himself, Eligio ended that portrait with a monologue that could be understood as a psychological search for the literary origins of the author of One Hundred Years of Solitude. “So, there he is, the author, as if he were not, as if he were someone else and not him, his double, knowing these news from Carmen Balcells, perhaps remembering those memories like her, how time passes, my mother , Blessing Alvarado, also knowing from the poet Álvaro Mutis, who called him from Mexico last night and shouted vociferously, sleep easy, my general because today is a historical date, that bastard work left me breathless, knowing how the readers devoured the book with much more furious anxiety with which Leticia Mercedes María Nazareno and her tiny division general were devoured alive by the sixty identical dogs of my misadventures ”.

That Eligio report, which includes other chronicles of concomitant times, has this footnote: “This chronicle was published in the Flash magazine of Bogotá, in February 1971, without signature and with the title of Gabriel García Márquez sinks in the loneliness of glory, and so it was also reproduced in Chile and Venezuela. This is therefore the first time that my name has been linked to this text ”.

Of such magnitude, as a literary study by a journalist who knows his lesson before asking questions, is the work that Eligio did in London with Guillermo Cabrera Infante in the late 70's. The author of Tres tristes tigres was still coming out of a nervous state. breakdown , he was already an exile dangerously harassed by the Cuban dictatorship and the young García went to his house and obtained from him such a quantity of highly literary details that from there arises one of the most beautiful portraits of Cabrera Infante as a writer. Of course , somewhere comes the boom that the Cuban was cornering.

"What is your name?". Eligio told him his own name, and Carpentier asked him for more detail. Until he ended up telling her both his last names. "And why didn't you tell me before ?!" "He never told anyone," says Tatis

Speaking of the origin of the term and also of its members, Guillermo tells Eligio: “The word boom applied to literature and not to economics was an Argentine invention. Specifically, from a magazine in Buenos Aires: hence the attribution to Hopscotch from its beginning. I believe that an injustice is committed against Vargas Llosa. It was La ciudad y los perros , which won the Biblioteca Breve prize and competed for the Formentor in 1962, the novel that made the public in Spain and Latin America interested in a fictional literature written in Spanish. But that same year, we must not forget it, Jorge Luis Borges won ex aequo with Beckett the Formentor prize, which made him an international literary figure, taking literature written in Spanish further than Vargas Llosa ”.

Vargas Llosa, of course, is the subject of Eligio's portraits; and no, the famous fight does not come out here. The report is titled The Good, the Bad and the Ugly , it was published in 1967 after the young Peruvian author passed through Bogotá and is, once again, a quick but profound portrait of one of the key personalities of the boom . “Tireless worker, pawn of literature, as he describes himself, Vargas Llosa did not stand still for a single moment. (…) He had time to investigate everything related to García Márquez's work prior to One Hundred Years of Solitude , a book that he would have liked to have written himself, as he publicly confessed in a report. And also in private his praise for the Colombian was even greater and enthusiastic, since according to Vargas Llosa that novel turns García Márquez into a kind of Amadís de Gaula de América, the author of one of those chivalric novels that the man likes so much. Peruvian writer".

Eligio goes to the cinema to which he would later become Nobel, like his brother, and goes to see one of Clint Eastwood. “There are murmurs in the room, someone tries to clap, another whistles. But a more powerful hiss dulls it: it comes from the screen. It is the music of the film that begins: it is Clint Eastwood, in the company of two other outlaws, in search of a few more dollars ”. Ennio Morricone putting silence in the room.

This treasure of the new Spanish-American journalism, compadre de Los Nuestro , by Luis Harss, contains other delights, such as the conversation with Jorge Luis Borges, the portrait with Cortázar, the nude drawing of Carlos Fuentes or the odd account of his hours with Onetti in the apartment that the Uruguayan had on Avenida de América in Madrid. On none of those avenues that he traveled did Eligio García leave a trace that he spoke from a tribe, a name or a surname that made his voice more powerful than those of any other. He was the man who wanted to be nothing but Eligio García, a writer, a journalist. The book would have to be taught in the schools of those who want to learn how to ask the writers.

He once competed for a literary award. "If it's not good, don't reward it," said his brother. They did not reward him. When the tumor that would end his life presented itself, Gabo provided all his help. "He loved him," says Tatis, "and he didn't want to be him." In any case it was, says his friend, "a bridge to him."

"A party of crazy people"

One day Gabo's sister reproached the recently deceased wife of the author of 'One Hundred Years of Solitude' for the obstacles that she put up so that any of the numerous Nobel siblings would approach him even by phone. Mercedes Barcha, who recently died in Mexico, the woman who put life in order so that the author of 'One Hundred Years of Solitude' could only dedicate himself to literature, explained: "You are a crazy party." "But you took the crazy older man!", Replied his sister-in-law. The dialogue came to mind because another brother of the writer, when in 2008 he was leaving knowing that he was losing his memory, explained in public that there would be no more books by Gabo . That infidence, like others, seemed inappropriate to Mercedes. Tatis says that she appeased “the temperament of Gabo's many brothers, who embodied the Aurelians and the Buendías with certain similarities, all of them oral, ungovernable, volcanic and peaceful narrators, but with exceptional nuances, such as Aida's serene wisdom, the Ligia's loving religious stubbornness, Margot's self-denial, Rita's mildness ”. In the midst of this universe of madmen and sane,“ Mercedes protected Gabo from assaults on the privacy and infidences ”of those close to her. But "her relationship with all of them was a curious mixture of loving and affective secrecy, wisdom, prudence and cordiality." Gabo, who had no pocket money, was managed in everything by La Gaba. He gave a house to the brother who did not have one, he was deferential to everyone and was always sure that Mercedes would also handle "the grudge department" which, on the other hand, did not have so much to do.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/XIAKA2R7MVHGZIECIEZ5XB5BZA.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/N2CBAPWTK5AYRIQDVR3SFGIKVM)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/Z3C74GDWPZH2JMJB4EIL7Q7S4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/KJKFJLLN25HIBCH7EI7AXP3X44.jpg)