The cocoricos find it difficult to pass in the research community.

After the announcement this week of the Nobel Prize in chemistry awarded to the French Emmanuelle Charpentier, ministers congratulated themselves in the name of tricolor research.

And teeth gritted.

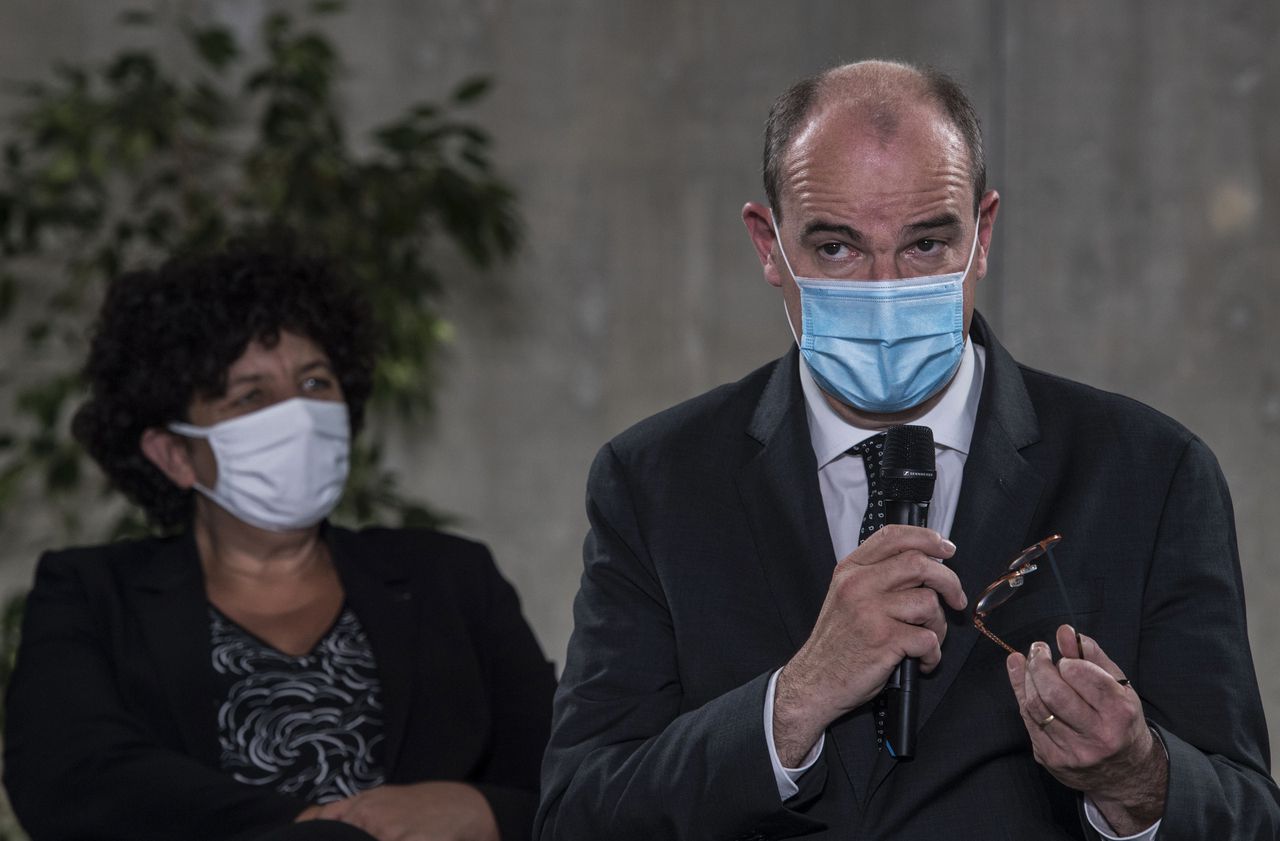

On Twitter, the Minister of Higher Education, Frédérique Vidal, expressed her "immense pride for all of our research and for French chemistry".

Prime Minister Jean Castex also praised the profession's “excellence” and “international attractiveness”.

My sincere congratulations to Emmanuelle Charpentier who is awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Jennifer A. Doudna for their work on molecular scissors.

An immense pride for all of our #research and for French chemistry.

#NobelPrize

- Frédérique Vidal (@VidalFrederique) October 7, 2020

Except that Emmanuelle Charpentier, who heads the very prestigious Max Planck Institute for the biology of infections in Berlin, has spent most of her career abroad after her French training.

“To boast of his work in this way gives the impression that research in the country is going well.

This is false, ”asserts Jean-Bernard Manent, researcher at Inserm in the field of neurosciences.

France "is at risk of dropping out"

"Recovery", "intellectual scam" ... The professionals of the sector have not mince words.

"If the politicians had said:

pride in French training

, it would have gone better," notes Amélie * (

the first name has been changed

), a 28-year-old researcher in environmental sciences.

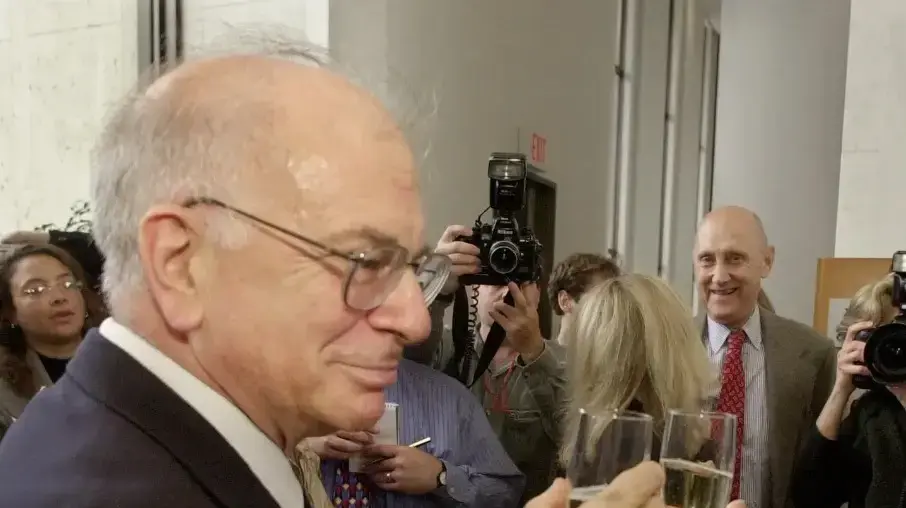

Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2016, is more understanding.

"Let us be proud, the contribution of France in this price is quite large", judges the scientist.

Emmanuelle Charpentier explained Thursday to France TV Berlin, why she was carrying out her work abroad: France "would have struggled to give (him)" the same means as in Germany.

"The health of research in France, as in other European countries, is not at its best and I am touched, even depressed, when I discuss it with my French colleagues," she developed in 2016 in an interview with The Express.

I don't know if, given the context, I could have carried out the CRISPR-Cas 9 project (

Editor's note: work for which it received the Nobel Prize

) in France.

"

🇩🇪🇫🇷 "I think that France would find it difficult to give me the means that Germany gives me".

👇 Meeting with Emmanuelle Charpentier, researcher at #Berlin, Nobel Prize in chemistry 2020. pic.twitter.com/zyOtBC6egz

- France TV Berlin (@FranceTVBerlin) October 8, 2020

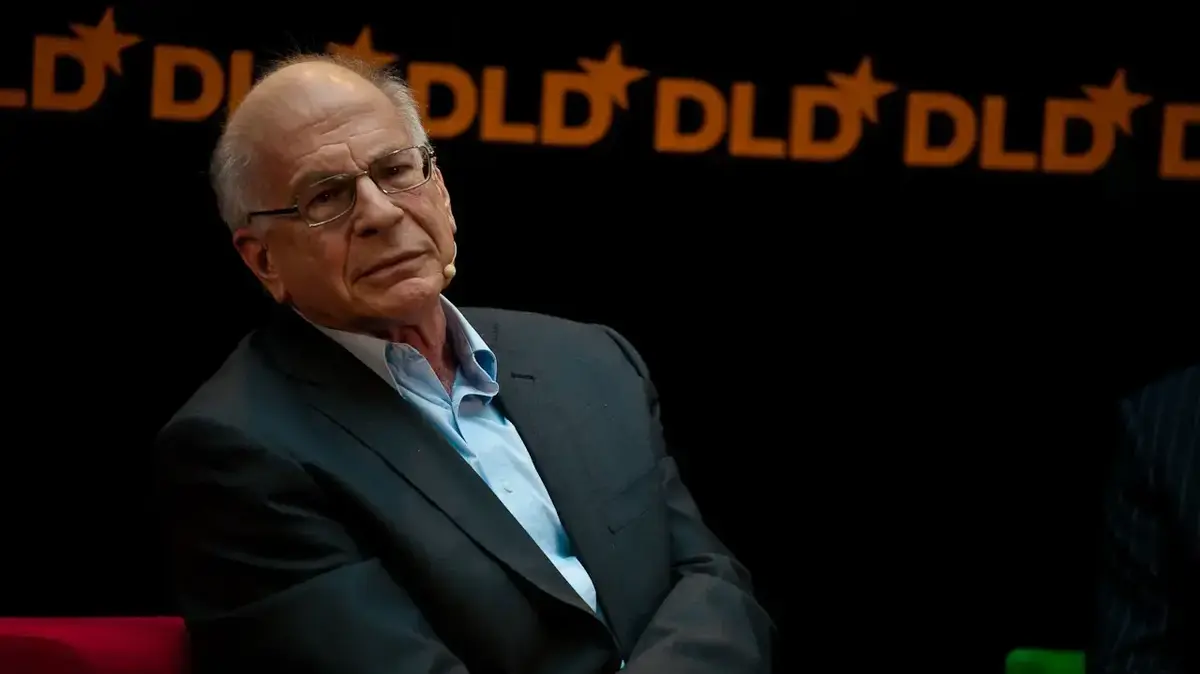

For Serge Haroche, Nobel Prize winner in physics 2012 and professor at the Collège de France in the chair of quantum physics from 2001 to 2015, “the case of Emmanuelle Charpentier clearly illustrates the problems” of the profession.

“The conditions for young researchers are not up to what is offered abroad.

"And the problem is" serious ": according to him, the country" risks dropping out in terms of research ".

Too low wages, not enough positions

After years of post-doctoral studies (fixed-term contracts in a research laboratory), a researcher obtains a position at 35 years on average.

“Almost ten years of seniority therefore, and we hire him for less than 2000 euros!

Annoys Patrick Monfort, secretary general of SNCS-FSU (National Union of Scientific Researchers).

The research programming bill (LPPR), which Frédérique Vidal came to defend in the Senate on October 7, intends to increase salaries.

From 2021, a lecturer or a researcher should be recruited for at least 2 minimum wage, or around 2,400 euros net per month.

"But abroad, it will remain much better: twice as much in Germany or the United Kingdom, three times as much in the United States ...", deplores the trade unionist.

Serge Haroche fears that this increase "will initially remain at too low a level".

Newsletter - Most of the news

Every morning, the news seen by Le Parisien

I'm registering

Your email address is collected by Le Parisien to enable you to receive our news and commercial offers.

Learn more

Another recurring criticism: the lack of positions in research.

“The further we advance, the fewer places there are,” explains Amélie from Germany, where she is doing her second post-doc.

Ultimately, the young woman would like to work in France, "to see friends, to be there for birthdays, weddings ...".

“But I'm not kidding myself.

There is no guarantee that a return to the country will be accompanied by a long-term job in research, ”she regrets.

Lack of resources "at all levels"

The professionals we interviewed unanimously point to a lack of funding "at all levels".

Starting with "the little everyday things, which count despite everything, like the premises, the fact of having a single office ...", lists Sylvia Serfaty, mathematician and professor at the Sorbonne University (formerly Pierre and Marie Curie University) as well as at New York University.

The teaching load also, twice as heavy in France, which "leaves less time for research".

Above all, researchers deplore the difficulty in obtaining credits.

"Here, the success rate is low, for lower funding amounts as well", continues the scientist.

“In the United States, the financial flow is not the same, in Germany also, in South Korea do not speak about it, notes Patrick Monfort, of the SNCS-FSU.

In the context of calls for projects, they recover money much faster than us.

"

In France, the budget allocated to the National Research Agency (ARN), which finances public research, stood at 553 million euros in 2019, according to a Senate report.

By way of comparison, the German equivalent of the RNA, the Research Foundation (DGF), distributes more than € 3 billion in research funding each year.

Limited risk taking

How to face international competition?

However, France has advantages that make it very attractive: excellent training, prestigious institutions, job security through civil servant status, full-time research positions (CNRS, Inserm, Inria) - "Which very few countries have," Sylvia Serfaty emphasizes.

"But if it is very elitist in training, it is much less thereafter, due to lack of resources", notes Jean-Pierre Sauvage.

"The institutions, the CNRS and the universities, should have substantial equipment and operating budgets to distribute to their researchers, enabling them to finance ambitious research over the long term which cannot be based solely on contracts finalized at short term, ”suggests Serge Haroche.

Still "very standardized", the French system indeed limits the "recognition of talent" and therefore risk taking, explains Ioanna Kohler, former director general of the Aspen Institute and author of the study "Gone for good?

French higher education expatriates in the United States ”(Institut Montaigne, 2010).

Researchers must climb "a whole series of levels" and are subject to "a fixed salary grid", she says.

“In America, if you're good, you are trusted, and the

value

you bring to college is reflected in your pay.

It's up to you to get results.

"

"We tried to bring Emmanuelle Charpentier back"

Asked about the reasons which pushed her to prefer the United States to France for her living, the neurobiologist Catherine Dulac explained in September that she had encountered "a kind of paternalistic behavior to the con".

“My post-doc worked very well, and I had opportunities to have my own lab in the United States, which I did not have in France.

I was told:

oh you are much too young to have your own budget, you don't have enough experience to be independent.

“Less than a month ago, the Frenchwoman received a prestigious American prize, the Breakthrough Prize, endowed with 3 million dollars for her research on parental instinct.

We have tried to bring Emmanuelle Charpentier back to her native country, says Serge Haroche.

“We would have dreamed of offering her a chair at the Collège de France, one of the most prestigious institutions, but we are unable to provide her with the working conditions and the credits she has at Max Planck”, he regrets. .

"We need great scientists"

To "enable researchers to excel in France", the Ministry of Higher Education plans to give 25 billion euros over ten years to the profession.

In addition to the increase in the remuneration of professionals, this envelope should allow public research to reach 1% of GDP (against 0.7% currently), as France committed to it twenty years ago.

“Some measures are going in the right direction, greets Serge Haroche.

But the catching-up is spread over too long a period, there should be an immediate effect, improving working conditions more quickly ", estimates the author of" La Lumière revealed "(Ed. Odile Jacob, 2020).

"If we want to be in the race, to have the best of the best, that will not be enough because things are not going fast enough," says Patrick Monfort.

"The major problems that we must solve, linked to global warming or the Covid-19 crisis, always require more science.

We need to improve the conditions which will make it possible to keep brilliant young researchers in France and to attract great scientists to the country.

It is a long-term investment, ”insists Serge Haroche.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/WWFMH3RJQFHGDLP4L4JLWOGC6Y.jpg)