A Colombian woman seeks to bury her father's body in her town, but finds that the cemetery is a minefield.

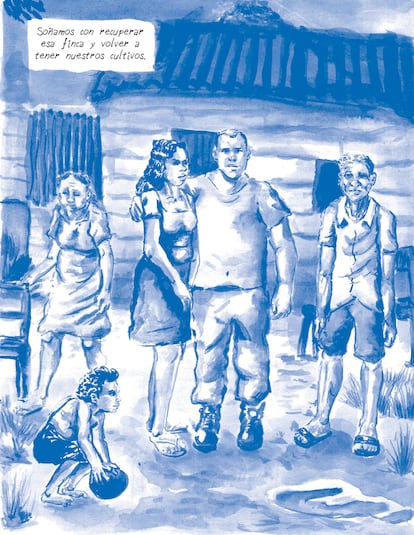

Some peasant families seek to rebuild their lives on the land from which they were displaced by violence, but find their homes overrun by weeds or surrounded by monoculture palm plantations.

A guerrilla woman thought she no longer had a family, but discovers when she demobilizes that one of her fellow soldiers was her cousin.

A girl in Bordeaux thought her mother had abandoned her, only to find out decades later that her mother disappeared in a torture center.

Stories like these, left by the war in Colombia, abound in everyday life, but they don't always find the best way to be told. Academic reports on what happened in more than half a century of armed conflict have few readers, as do judicial rulings, even though they are fundamental contributions to the truth. But in recent years, in the world of letters, these complex life stories have found a new niche to be heard by a wider audience: the graphic novel or comic.

“What comics give you is a quick, easy, engaging read,” says Spanish illustrator Javier de Isusi, who published

Transparents

in 2021, a moving graphic novel about a woman in Bordeaux searching for the truth about her mother and other stories. of exiled Colombians. "People always need to tell each other stories to understand reality and comics are a way that takes advantage of the vehicle of drawings," adds Isuso. “The text can provide you with the facts, but the drawing enters through another place other than the brain: it does not enter through a place as cognitive as the letter, but through a more sensory place. The drawings always allow us to enter from the side of emotion”.

Isusi published

Transparents

in 2021 after being contacted by the Truth Commission, a transitional justice institution that was created after the peace agreements between the FARC guerrillas and the Government in 2016, and which seeks to make the debate for collective memory of the war is as wide as possible. "Those of us who left Colombia became transparent in the eyes of those who stayed," says one of the characters in the novel. "As we don't count anymore." According to UNHCR figures, between 2000 and 2012, at least 400,000 Colombians were forced into exile.

One of the main representatives of the Truth Commission, Carlos Maristein, allowed the illustrator to have access to documents, testimonies and invited him to meetings with children of exiles whose stories inspire this novel.

"Of all the comic scripts I've written, this is one of the most difficult I've done," says Isusi, who won the national comic award in Spain in 2020.

Transparent Fragment

"Comics have always been closely associated with the urban, with fantasies, with humor and adventures, but for us as a group it was interesting to be able to take our job out of the city and out of our comfort zone," says Colombian Pablo Guerra, founder of Cohete Comics, one of the few publishing houses in the country that has been dedicated to graphic novels since 2016.

Guerra is the co-author of

Caminos Condenados

, a 2016 novel that he describes as a documentary comic and that was based on an academic study on the forced displacement of peasants in a rural area of the Colombian Caribbean called Montes de María.

There, teak and palm logging companies took over the land abandoned by peasants during the worst years of the violence.

"They are burying us in our own house," says one of the peasants in the novel.

Damned Paths Fragment

In the documentary comic, explains Guerra, it is evident that what is reported about the armed conflict is mediated by the illustrator: it is impossible to ignore that it is a drawing, a caricature, and not a photo.

But precisely for this reason it is a genre that has the potential to visually recall, working together with the people who lived through the war, what happened and that no camera could record.

That which only recorded memory.

"A comic is made of panels in sequence, but we have the challenge of reconstructing a territory from those panels, and each panel was a window into how that territory is remembered by someone," says Guerra.

In addition to directing Cohete Comics, he was also the co-author of

La Palizúa

and

Sin Mascar Marca.

, two graphic novels from the Centro de Memoria Histórica —another transitional justice institution— about two peasant communities that were displaced by armed groups. "Communities have different ways of how they want to carry out their reparation process and these two specifically asked that as part of the process there be a graphic narrative that would tell what happened there," says Guerra. According to official figures, at least six million people were displaced from their homes during the conflict in recent decades.

Comete Cómics is a label that is part of Laguna, an independent publisher that in 2021 won the national poetry award in Colombia for a book that, although it is not a graphic novel, also combines poetry with illustrations in a very innovative way.

La Mata

, a collection of poems by Eliana Hernández and illustrated by María Isabel Rueda, is a book about a painful and iconic massacre carried out by paramilitary groups in 2000 against another Caribbean town, El Salado, and of which they were victims at least 105 people. The town was almost deserted.

"What do you think kills her, sleepwalker, after seeing everything?"

asks the poem that recounts the massacre from different voices while drawings of the plants take over an abandoned house in the town.

For his research, Hernández relied on the first report of the Historical Memory Commission on El Salado, press reports, but also sources that explained the flora in this region of the Colombian Caribbean.

Fragment of La Mata

"María Isabel's drawing creates an effect analogous to what poems do, but from a perhaps less conscious point of view," says Hernández.

“It suggests a violence that encompasses the space, taking over the voices, and in the end it also accounts for a transformation.

I think it gives the book a darkness that it needed.”

In another corner, the perpetrators of the war, not only the victims, have also reached the comic strips. At the end of 2020, the Spaniards Gala Rocabert Navarro and Anna-Lina Mattar won the Fnac-Salamandra Graphic International Graphic Novel Prize for a book about the demobilized FARC entitled

En el ombligo

. Published in December in Spain (it will arrive in Colombia at the end of January), this novel is also inspired by real events and tells the story of a social sciences student who travels as a volunteer to one of the transitory territories where 248 guerrillas gather for their demobilization and reintegration process. In 2016, it is estimated that around 13,000 guerrillas agreed to lay down their arms in the peace process.

“After so many months here, I notice that there are those who still do not trust me,” says the student, Gala, inspired by the author of the book who lived in this camp between April 2017 and September 2019. “I have been understanding it” , add the character. "The experience of war leaves fears, misgivings, mistrust...both with the people with whom they shared and with the new ones."

“The format of this book is very much like a field diary: it doesn't have closed panels and it has some bits of text,” explains Anna-Lina Mattar, who illustrated the novel using Navarro's field diary.

"If it's about portraying very intimate subjects, like these, if you draw it it's less invasive for people," says Mattar, comparing this genre to the documentary or photo essay.

A camera can be so intimidating that it can silence the interviewee.

An artist, on the other hand, is more silent: he listens calmly and then draws.

Fragment of In the navel

"I have seen the graphic novel as an opportunity to reach a wider audience and not just an academic one," says Navarro, who studied anthropology and sociology but decided to move to the graphic format in order to share his experience in a society where demobilization of the FARC remains a polarizing issue in Colombia. "What I have tried in the book is to transcend that polarization, I have tried to go further," says Navarro. "For example, all the characters that come out are everyday characters from the base, there are no political or prominent characters, and I see what happens in people's day to day, because I think it is from there that the peace. I would like to overcome that discourse of war that separates victims and perpetrators”.

Post-conflict graphic novels show that peace, as promised by political speeches or legal agreements, is much harder to deliver. The exiles fear returning. The displaced cannot manage, among the palms, to rebuild the life they had. The demobilized guerrillas do not always receive the support they were promised. Since the end of 2016, almost 300 ex-combatants are believed to have been killed in Colombia. Post-conflict is a more difficult process than it was in 2016.

Natalia Jiménez is a member of a non-governmental organization called

Somos CaPAZes

that teaches peacebuilding and recently decided to venture into comics. In the first half of this year they will publish

Tierra Removida

, a graphic novel about a woman who travels with her father's body to her hometown to bury it there, but finds that the cemetery is full of mines placed there during the conflict. The Government, the comic shows, has been slow and ineffective in the process of demining the cemetery.

"It's been 15 years since we buried anyone," says the town's mayor in this graphic novel in which a policeman, a demobilized FARC member, and another paramilitary manage to work together despite having been deadly enemies. The characters, as in the other comics, are based on true stories. "It's time to stir up the earth and replant," another character answers later.

“We made this comic after ACDI/VOCA –a USAID organization– carried out a study that revealed that, in the municipalities that were particularly hard hit by the armed conflict, 85% of young people thought that there had been no progress in terms of peace agreement of 2016″, says Jiménez.

He refers to a survey of 170 municipalities that have had special development programs since 2016. “And yes, there are many problems, it is true, it is also true that there has been progress.

We wanted to reach these young people but we did not want them to feel that we were teaching them”.

Broken Earth Fragment

The illustrator of this graphic novel is Miguel Vallejo, known as 'worm', who prefers to use the word comics to talk about comics, and who considers that the country is experiencing a renaissance of the genre. He remembers a unique effort in the world of Colombian comics, in the seventies, when a renowned Colombian sociologist named Orlando Fals Borda tried to make comics about the history of peasant movements that claimed their right to land in the Caribbean.

“What Fals Borda did was an important reference but I think that unfortunately he was not so well articulated editorially,” says Vallejo. “Now I do feel like we have an opportunity to retell that story, our story, on our own terms. And it's great to do it in a country where comics are not something as structured as it is in France or the United States: we can drink from anywhere, that is, from different structures. Elsewhere they look for authors or publishers who have the same lines, who are above all what Marvel or DC Comics want.

The history of war can be told in different ways: sentences, academic books, movies, novels, songs, graffiti. Fortunately, no one has a monopoly. Now the graphic novel is added, which, as Vallejo says, "was previously seen as something for children." When the novel "

Transparents

" was published , Francisco de Roux, a well-known Jesuit priest who heads the Truth Commission, wrote a prologue in which he says that the comic "is not a pamphlet to flip through or a text to read on the run." It is a book to listen, in another way, to those who lived through the war. "It is a call to walk with other paths that continue," he says. "Take it seriously."

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS América

newsletter

and receive all the key information on current affairs in the region

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/62WTZ2YGTKOGTJ6OXJW67JCCME.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/DNRYCWU6TFHD5AKHCDDWYTYIRY.jpg)