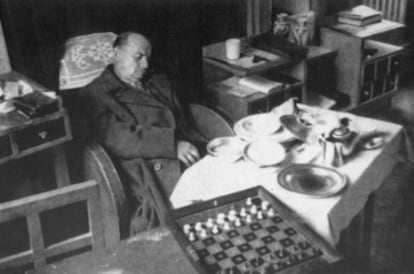

Alexander Alekhine in England in 1938. Keystone-France (Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

Of the hundreds of fascinating characters that chess has produced, the Russian-French Alexander Alekhine may be the one who generates the most feelings of admiration and disgust.

The French novelist Arthur Larrue, expelled from Russia for his involvement in the dissidence against Vladimir Putin, recreates in

La diagonal Alekhine

(Alfaguara) the convulsive last seven years of a biography that he gives for several films.

And he emphasizes some disgusting anti-Jewish articles written by the world's only dead champion in possession of the title.

More information

Alekhine, a genius for several films

Morning of Sunday, March 24, 1946, room 43 of the Hotel Parque de Estoril (Portugal). Alekhine (whose transliteration of the Cyrillic alphabet should be Aliojin, according to the RAE and EL PAÍS Style Book, but hardly anyone calls him that) is found dead at the age of 53 next to a board with the pieces in their original position and the remains of your dinner. The official version is that he suffocated from a piece of meat stuck in his throat. But, as Larrue glosses in his novel with a vigorous style and great mastery of the craft, not a few wanted his death for very different reasons, and everything indicates that he did not die naturally, despite the fact that his extreme alcoholism announced a short life.

Alekhine (Moscow, 1892) was imprisoned for more than a month in Germany when the First World War surprised him at the Mannheim tournament in 1914. His family, an aristocrat, was expropriated after the Bolshevik Revolution.

And he, imprisoned again, in Odessa, and sentenced to death, but pardoned (by Trotsky, according to some sources, although it is not clear) due to his great fame as a chess player.

He later managed to leave the Soviet Union because he was married to a Swiss journalist, whom he abandoned when he arrived in Paris.

All the women he paired up with were wealthy and older than him.

He dethroned the legendary Cuban world champion José Raúl Capablanca in Buenos Aires, 1927. He lost the title due to alcoholism in 1935 against the Dutchman Max Euwe, whom —after an abstinence cure— he clearly defeated in a revenge duel, in 1937. He was astonishing in his exhibitions of blindfolded simultaneous games (with his eyes blindfolded or with his back to the boards, memorizing the situation of all the pieces in each game).

Larrue's novel takes place from 1939, when Alekhine returns from a trip to Buenos Aires and settles in Nazi-occupied France, who pressures him to write anti-Semitic articles.

Two aspects of this story have been debated for years: whether it was he who actually wrote them;

and, if so, if he had a choice or should choose between writing them or death.

Larrue is blunt: “There is no doubt that he wrote them, although chess players would prefer the theory that he had no choice or that they were written by others.

It is true that he was in an occupied country.

And that history is written by the victors.

But he was a Russian aristocrat, with a long tradition of anti-Semitism.

In other words, he is a man of his time and of his geographical origin.

At that moment,

Alekhine, dead, in a hotel in Estoril, on March 24, 1946.

To clarify the extent to which Alekhine really thinks what he signs in these articles, Larrue compares them to how much the controversial champion wrote about chess: “In his 18 game analysis books and numerous technical articles, Alekhine searches for scientific truth.

On the contrary, their anti-Jewish articles are a combat tool.

Alekhine had a choice, but he preferred not to."

Larrue was expelled from the Herzen University of Saint Petersburg, after working for four years as a professor of French literature, when he published the novel

Partir en guerre, in

which he bears witness to his close coexistence with anti-Putin dissidents.

And he sees Alekhine as a product of a historical hallmark of most Russians, "who prefer their leaders to be stronger than fair."

He specifies it like this: “The Russians highly value strength.

They relate respect to fear, in a somewhat childish way.

If the government does not instill fear in them, they lose respect for it, as happened to Gorbachev.

The vast majority of Russians know that Putin is a criminal and a thief, with absolute cynicism.

But they also know that Putin creates fear, not only within Russia but in the world, and they love that."

The hero of his novel, Larrue emphasizes, is not Alekhine, but Rudolf Spielmann, a very brilliant Austrian-Jewish chess player, multiple winner of Alekhine and Capablanca, to whom he dedicates only a few pages: “Spielmann, who allowed himself to starve , represents the intelligence and sensitivity that always end up appearing to demonstrate the fragility of that supposedly devastating force, which can fascinate many people. That force is false, unhealthy, deadly, and based on lies."

Beyond the chiaroscuro of a tormented chess champion, Larrue chose Alekhine because he wanted to “write a novel about the limits of loneliness and the pride of a single man, a chess player without a team of analysts or a state that supports him.

That solitude is connected with that of some poets or with that of the French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline, who has had so much influence on me.

And it is the darkest and most evil thing about chess, which in Alekhine's case led him to disconnect from the community to which he belonged, that of chess players”.

So to the well-known loneliness of the long-distance runner is added that which Larrue has discovered: “That of the world champion, that of the best in his activity.

I wonder if that position does not lead to disconnection from the real world.

From that point of view, I find a similarity with Napoleon Bonaparte when he sat on a throne after dominating Europe”.

Although the French novelist finds "a great connection between chess and literature, because chess is a mirror of the world, and allows artists to illustrate it through chess",

La diagonal Alekhine

He had a special difficulty: “Loving the character, empathizing with his positive side so that the novel also reflects it.

I would have loved to play chess like Alekhine.

But the rest of his life is, shall we say, much less desirable”.

The penultimate period of Alekhine's life, just before his retirement in Estoril, was spent in Spain, where he gave numerous exhibitions of simultaneous games during which he was capable of downing a bottle of cognac.

He also worked for a short period with the Spanish child prodigy Arturo Pomar (1931-2016), from a Chueta Jewish family, whose peculiar life —as well as that of world champion Bobby Fischer, a pathological anti-Semite—, inspired the award-winning novel

El peón

(Pepitas pumpkin),

by Paco Cerda.

In order not to excessively disperse the plot of his novel, Larrue does not deal with Pomar in it: “I apologize to the Spanish chess players.

I know that his biography is also novelistic ”.

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber