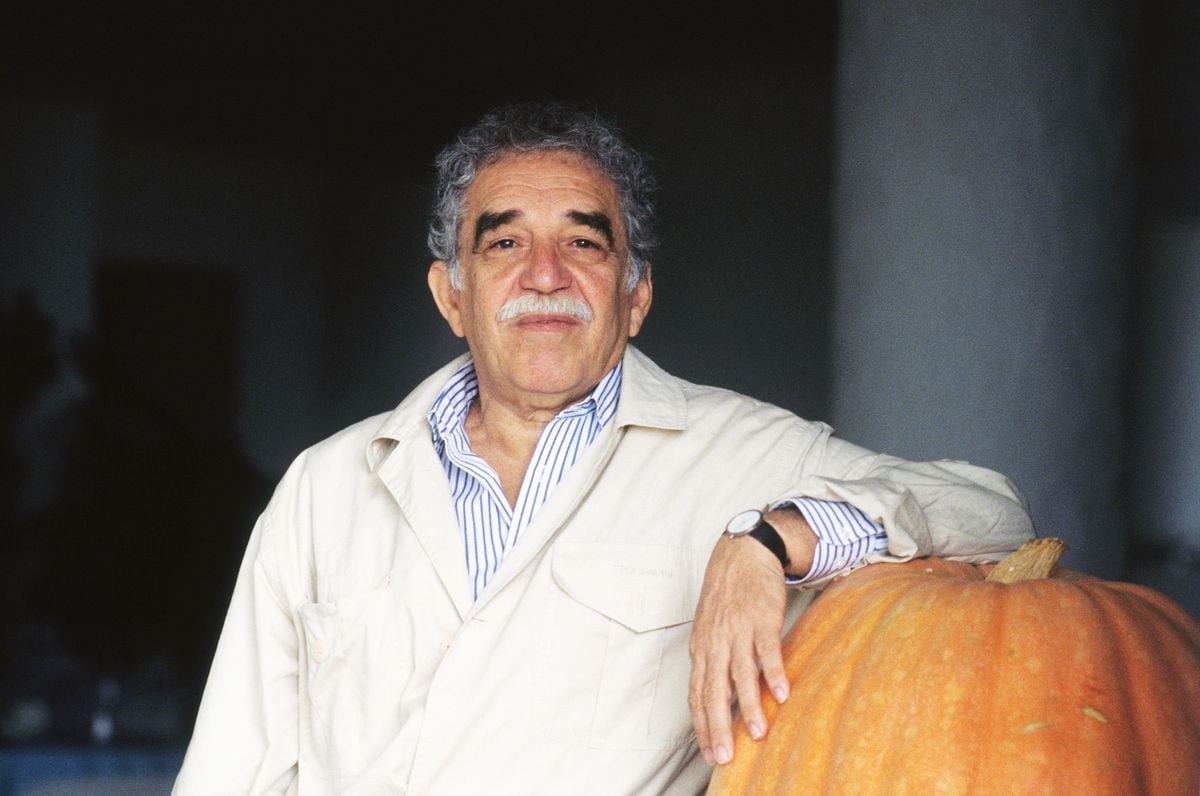

I wrote the first and, until now, the only complete biography of Gabriel García Márquez.

It came out in English in 2008 and in Spanish in 2009. I researched it and wrote it between 1990 and 2007. It was not an "authorized" biography, but it was written with the novelist's approval—I always said it was "tolerated"—and with a certain level of cooperation sometimes very generous.

When García Márquez died in 2014, I wrote an afterword for a hypothetical second edition.

That epilogue has not been published yet and I have considered it in some way a

work in progress

(“you never know”, I told myself).

A week ago some things changed in the "world" of GGM.

More information

Indira, the secret of the patriarch Gabriel García Márquez

Sunday, January 16, 2022, 1:41 PM.

Anonymous email.

“Another

well-wisher

”, I thought.

No message.

Link to an article titled

A daughter, the best kept secret of Gabriel García Márquez

.

“Finally”, I said to myself, “everything arrives.”

However, I was taken aback by the impact of the news on my state of mind.

Sunday, January 16, 2022, 15:19 PM.

Facebook.

A friend comments from Colombia: "Gerald Martin, you also had it well guarded... Gabo never ceases to surprise us even after his death."

Sunday, January 16, 2022, 3:51 PM.

Email.

Another friend scolds me: "So you've had secrets about Gabo with us!"

The next day an English biographer asked me the same question

(“Did you know?”)

and the next day another American biographer: “A friend just forwarded this to me.

Were you aware and, if so, were you keeping it quiet out of loyalty and discretion?

They are good questions.

And the messages keep coming.

Among them one from EL PAÍS.

I did my biography of García Márquez in another time, another world.

When I began my long and arduous (and exciting) job in 1990, email and the Internet were just getting started for the vast majority of people on the planet (the invitation to write the biography came the same way it would have come five hundred years ago). years: in letter form).

When I finished the biography in 2007, my use of the internet had been very limited because the uploading of Latin American academic and literary information had not yet taken off and I had worked with books and documents in libraries, newspaper archives and archives, in addition to countless long interviews personal.

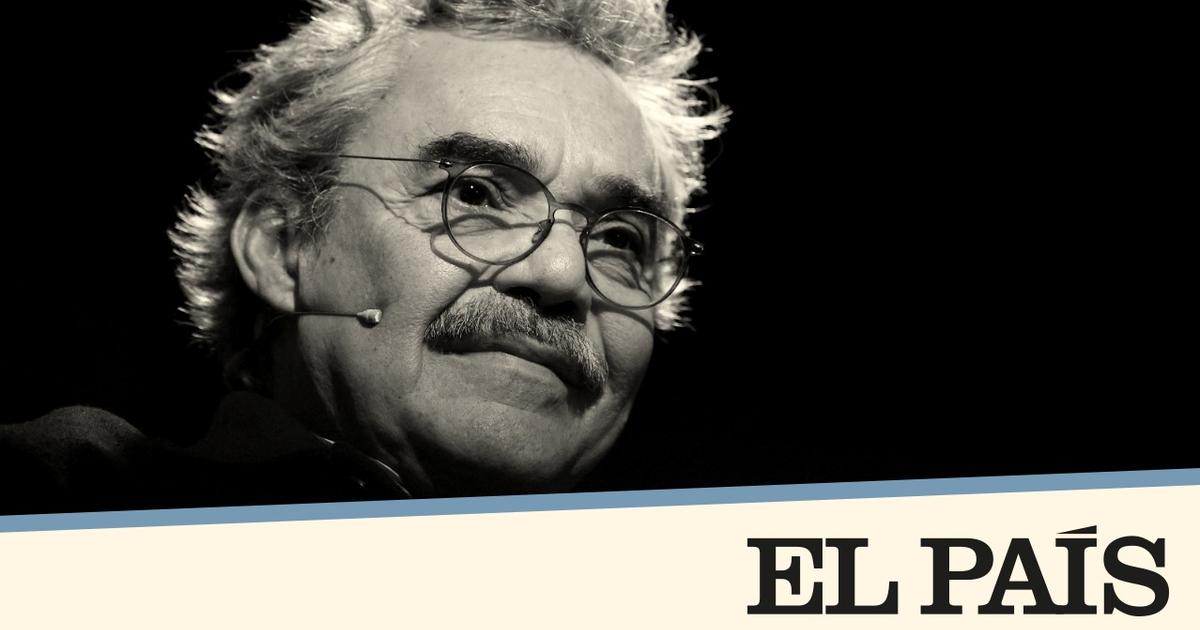

Gerald Martin, biographer of García Márquez, in 2019 in Madrid.BERNARDO PÉREZ

Now, in 2022, I am writing another biography from a small English town and have not visited a British library since the time I started it ten years ago;

The expansion of Latin American content on the Internet has been incessantly exponential and the problem is not to get information, but to discipline oneself and protect oneself, somehow, sometimes desperately, from the tsunami.

I communicate daily with Spanish and Latin American friends by email and I read EL PAÍS (the first leg of the daily trip, because studying and understanding the Spanish and Latin American panorama of the last 50 years without this newspaper is unimaginable), and a series of Latin American newspapers essential, every morning.

I live immersed in thousands of data and messages.

Following my convictions and my customs, I decided not to participate in the discussion of the revelations. I left a concise message on Facebook (I hardly ever visited that paradise anymore) and I told a Cartagena journalist who works at Efe and had contacted me, and said that I was not going to make any more comments. Trying to explain myself, I said without any pejorative intention that a biographer is not a journalist and that they are two closely related but different professions (first clarification: I don't really consider myself a biographer either, I am a man who has written two biographies; second clarification: I never I forget that García Márquez himself always prided himself on being a journalist and was, in fact, one of the great reporters of the 20th century).

Most of the reactions approved this statement, but inevitably two or three dissenting voices appeared: “I respect what Martin says, but ignoring topics that are a clear and important part of someone's biography is a biographer's duty, if you will. remain independent.

Writing biographies omitting definitive things does not seem serious to me.

It can be delicacy, respect, whatever.

But it does not attend to the commitment with the readers”.

And “A biographer is a biographer, and not an employee of the biographee… these omissions detract from the writer's credibility in the eyes of his readers.

One wonders how many other 'inconvenient' situations the biographer didn't tell us about him?

Despite the fact that no revelation had surfaced prior to the writing of my biography in 2006-2007, and I knew nothing of a possible daughter of the writer at the time, these interlocutors, both eloquent, meant what they meant. They are within their rights and thousands of other people will follow them and say similar things, many of them equally irrelevant. We are where we are (we are in Babel/Babylon and we are billions).

Later, more violent comments would come out directed not so much at his biographers but at the writer himself (and even, in some cases, at the putative mother): for example, “Gabriel García Márquez and his family is vile without limits, it is a infamy".

And the first journalistic comments appeared

(The Autumn of Patriarchy

was one of the first titles and one of the best).

Indira Cato, daughter of Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

The news had been revealed in

El Universal

of Cartagena, Colombia, the newspaper in which García Márquez became a journalist, by another journalist from Cartagena, Gustavo Tatis Guerra, who has commented on García Márquez for more than thirty years and published a book on Gabo a couple of years ago. He knows Gabo's family well, I know him well, he has interviewed me a couple of times. Justifying his

outing

of the daughter and her mother, explained: “The secret fell on my shoulders, while the two biographers of García Márquez wondered who was going to tell it.

And the fingers discreetly pointed at me.

Tatis seems to suggest that I and Dasso Saldívar, García Márquez's Colombian biographer, were hesitating and somehow decided that he, Tatis, would be the right person to drop the bomb.

I have a respectful relationship with Saldívar, but we have only seen each other three times in our lives and never alone.

I would never have participated in such a discussion or negotiation, for various reasons, and there must be some misunderstanding.

Neither he nor Tatis contacted me in the weeks and months leading up to the reveal.

I don't usually deal with these incidents,

I have never talked about my ups and downs and friction with García Márquez because I have never talked much about my relationship with him and they were beside the point;

on the other hand, it has always seemed a bit indecent to me to write about a person while one is researching his life story.

I plan to tell that story—my relationship with Gabo—some day, but who knows if life will give me permission.

It is true that my biography was ultimately generous (and why not?).

Still, perhaps it would be helpful if this seemingly docile and flattering biographer (according to some snap comments like those quoted above)

I gave some examples because, reflecting on the revelation of the existence of a daughter of García Márquez, I seem to remember that I have traveled between such moors and rocks more than once.

In the biography I had to measure what things to reveal and what things to leave out.

As in all “reporting”, be it journalistic, historiographical or biographical.

I decided, to the outrage of many Colombians, to mention the relationship that García Márquez had in Paris in 1956, despite his commitment to Mercedes Barcha in Barranquilla, and that ended in a pregnancy and the death of the baby who would have been the first “son of Garcia Marquez”.

I mention it because I discovered that "the mother" had inspired several important characters and two central themes in García Márquez's narrative work and had continued to be important in his later life;

and also because I judged that she "deserved" to be in the book and she, after thinking it over, agreed.

I met Tachia Quintana in Paris in March 1993, married for many years to a French cosmopolitan engineer whose birthday was the same as mine, February 22. Tachia had had few lovers. One was Blas de Otero. Another was Gabriel García Márquez. We walked, talking, through the same streets of the city that she and García Márquez had walked in the mid-1950s (to tell the truth, my conversations with Tachia never stopped). Months later, at García Márquez's house in Mexico City, biographer and biographee had a historic conversation: definitive and defining. Later I would remember in the biography: “I steeled myself and asked him: 'And Tachia?' At that time there were very few who knew about her, and even fewer who knew the history between them, even in broad strokes;I guess I had expected it to slip past me. He took a deep breath, like someone watching a coffin slowly open, and said, 'Well, it happened.' I asked him, 'Can we talk about it?' 'I do not answer myself. It was on that occasion that he told me for the first time, with the expression of a funeral director who with determination closes the lid of the coffin again, that 'everyone has three lives: a public life, a private life and a secret life. '. Naturally, public life was in full view of the whole world, I simply had to do my job; from time to time it would give me access and allow me to better understand the private life, and evidently I was expected to deduce the rest; As for the secret life: 'No, never'. If it was anywhere, he gave me to understand, it was in his books. I could start with them. 'And anyway,do not worry. I will be what you say I am."

These two sentences, especially the first, have been cited many times after the publication of the biography, but for some time, and despite his remarkably generous and sporting reaction, I felt a certain estrangement in my relationship with García Márquez that only ended when I got sick in mid-1995 (in 1996, when I was convalescing in France, Gabo managed to locate me by a miracle —that miracle called Carmen Balcells— and we had an affectionate conversation. I told him that I had returned to my biographical work. Days later a message arrived. signed copy of his new novel,

News of a kidnapping,

to my French hideout with the dedication: "To Gerald Martin, the madman who persecutes me").

to buy flowers, always chatting and exchanging questions, when Gabo was busy or late.

He granted me what remains the only long and intimate interview of his life (more than three very intense hours) whose full content I have not yet revealed.

Mercedes had consulted Gabo: "Very well," she said, "I will finally know what you think of me."

Our estrangement lasted several years—it didn't break my relationship with Gabo—yet I published what I wanted and should publish in the biography, and eventually we reconciled.

I fully understood his irritation.

It is not a question of killing the messenger—also very human—but a very natural difference of opinion about the imperatives and duties of a trade and loyalty and gratitude towards people.

when Gabo was busy or late.

He granted me what remains the only long and intimate interview of his life (more than three very intense hours) whose full content I have not yet revealed.

Mercedes had consulted Gabo: "Very well," she said, "I will finally know what you think of me."

Our estrangement lasted several years—it didn't break my relationship with Gabo—yet I published what I wanted and should publish in the biography, and eventually we reconciled.

I fully understood his irritation.

It is not a question of killing the messenger—also very human—but a very natural difference of opinion about the imperatives and duties of a trade and loyalty and gratitude towards people.

Mercedes had consulted Gabo: "Very well," he said, "I'll finally know what you think of me."

Our estrangement lasted several years—it didn't break my relationship with Gabo—yet I published what I wanted and should publish in the biography, and eventually we reconciled.

I fully understood his irritation.

It is not a question of killing the messenger—also very human—but a very natural difference of opinion about the imperatives and duties of a trade and loyalty and gratitude towards people.

Mercedes had consulted Gabo: "Very well," he said, "I'll finally know what you think of me."

Our estrangement lasted several years—it didn't break my relationship with Gabo—yet I published what I wanted and should publish in the biography, and eventually we reconciled.

I fully understood his irritation.

It is not a question of killing the messenger—also very human—but a very natural difference of opinion about the imperatives and duties of a trade and loyalty and gratitude towards people.

I was also the first person to reveal Gabo's dementia. It seemed to me that the first complete biography of García Márquez's life could not omit the drama that he was experiencing in the last years of his life. I will believe, until the end of my own life, that he implicitly asked me to do it, because it was his truth, and to escape the anguish he felt (in 2002 the dedication he sent me in one of the first copies of

Live to tell

the story came saying, "To Gerald, with what's left of my memory"), but I would have revealed it, despite my own anguish, anyway. Curiously, no one paid any attention to me and poor Jaime García Márquez, his younger brother, had to take the blame years later when a verbal oversight reached the ears of the press.

Gabo and I were human beings. When I went to see him in Mexico City in 1999 I had just been told in Pittsburgh that I had a recurrence of my cancer. Incredibly, he had called me to tell me that he had also been diagnosed with the same cancer—lymphoma (“we are now colleagues,” he told me)—and I had decided to visit him as soon as possible to cheer him up without knowing what the doctors were going to reveal to me next. the eve. During my four days talking and eating with Gabo and Mercedes, they—very scared, naturally—celebrated my survival, the demonstration that this cancer really wasn't such a big deal. I did not have the heart to confess to them that my own situation seemed to contradict that optimistic reading of my case. Did I do good or did I do bad? Who knows?

And now, ladies and gentlemen, the disappointment and anticlimax carefully deferred by the perfidious Englishman (did I mention I'm English?) until the end of his article.

You will have to forgive me for the scam!

As for Indira Cato and her mother Susana Cato, I know very little: more than what is said in the newspapers up to now (it is that these are

"early days")

but very little.

I haven't talked about them because I don't know them and probably, even knowing them, I wouldn't have commented on the news;

my job is another.

I always need “more time”.

In the first months of my biographical research I heard the name “Susy Cato” several times.

But I heard many names and they told me many anecdotes (I didn't ask, but they told me).

From time to time there was talk of a Cuban lover of the writer.

When I saw some articles signed by Susana Cato and published in the Mexican press, my intuitions began to tell me: "Maybe... maybe a Mexican who has lived in Cuba."

Susana Cato, in a YouTube video.

This theme—passion and its dramas—has obviously seemed very important to me, especially in the case of a writer whose central motives are power and love, but they have never been my obsession during my research.

In those years there was never any talk of a daughter.

A year or two after the publication of the biography I began to hear rumours.

Google already worked very well: what's more, it was already indispensable.

One day, when I entered “Susana Cato Ciudad de México” the name “Indira” appeared.

It was enough for me for many reasons that are not the case in this chronicle: Gabo had a daughter.

Of course, I didn't really “know” yet and haven't tried to find out.

Meanwhile, several friends and other people have “confirmed” it for me: I put the word in quotes, but it is already obvious to me that they were right;

but who knows what they would think of the “biographer of García Márquez”.

It doesn't matter either.

Here a confession. Sometimes the biographical sense of smell works —in fact, and rather autobiographically, my nose is enormous— and I should tell you the following. When I finished the biography I decided that I wanted to include Susana Cato's name in the index. I was "sure" and "I knew" that it was an important name, but in reality I didn't know, it was just intuition. I inserted a reference to an article of his dated 1989 in a footnote and, in the text of the book, another reference to another article of his dated 1996 so that it would appear not only in the notes but also in the index. It was a kind of bet with myself, like an encrypted message in a bottle thrown into the sea that eventually returned to the beach. I hope it is a good omen and that everything goes well for both, mother and daughter.

Some readers —and not a few journalists (and we all feel like journalists now, in the days of Facebook and Google)— seem to think that having poked my vain nose into Gabo's affairs—an idolized or hated celebrity, depending on—it is now up to me to be permanently on the alert to bring out or underline scoops, “revelations” and “secrets” and to comment on them—like a Wikipedia compiler, perhaps. I repeat that I am not a reporter, a job that I respect, but that is not mine; I am a biographer, historian. (Historian, among other things, of the interface between public and private, between cold distance and warm closeness. No one understood the game better than Gabo). What does concern me is to avoid impertinence and clichés, if I can.

I don't know when a second edition of my biography will be published and, besides, I'm on something else. If it comes out one day, it will have scoops and new revelations, but none more extraordinary than "García Márquez's daughter." I will not forget, however, that Indira Cato is a person, a human being, a young woman totally independent and, surely, self-determining. It is not a character or a personality. It behooves us to assume and accept that she will always decide who she is, what her identity is, what she wants to say, what secrets she wants to keep, what she wants to be in life. For now, others are speculating, others are inventing it, almost always without any basis for doing so, and one would have to hope that none of them will have a lasting and definitive power over it. I am part of the "round", I know (here I am),but let me step out of the loop for a moment and simply and sincerely wish you all the best.

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/KJKFJLLN25HIBCH7EI7AXP3X44.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/N2CBAPWTK5AYRIQDVR3SFGIKVM)