The idea arose, like so many that go nowhere, in the tumult of a dinner with friends. Jason Epstein, who died on Friday at the age of 93 at his home on Long Island, and his wife at the time, Barbara Epstein (1928-2016), had invited the couple made up of critics and critics to their apartment in upper Manhattan. writer Elizabeth Hardwick and poet Robert Lowell. It was the winter of 1962-1963 and New York was in the midst of a newspaper strike, protesting low wages and the imminent automation of the printing presses. In those dry months, the four of them especially missed reading

The New York Times Sunday book supplement.

.

Jason Epstein, an influential editor at Random House with little free time, had flirted with the idea of distributing the London weekly

Times Literary Supplement in the United States.

Instead, he suggested taking advantage of the sudden lack of information to launch his own version: a publication with long essays on politics, literature, art and ideas, which, unlike that one, would be fortnightly.

More information

The man who hid behind the books, by Luis Gago

Lowell put up $4,000.

Hardwick was appointed editorial adviser.

And Barbara Epstein and Robert Silvers, who came from Harper's, a literary monthly, shared the command of the magazine.

The first issue of

The New York Review of Books

(NYRB) came out on February 1, 1963 with a cover full of lyrics and an impressive spread of contributors (from Auden to Sontag; from Gore Vidal to Adrienne Rich), who placed under the Headboard.

All the protagonism was taken by the commentary of the new book by James Baldwin:

The next time the fire,

book

which is still relevant in Biden's racially tense America.

First cover of 'The New York Review of Books', in February 1963.

The success was immediate, thanks in part to the idea of Jason Epstein, marketing

genius

with the soul of a man of letters (and vice versa), to distribute free copies in university bookstores.

The 114-day strike ended, but the

NYRB

continued.

And it goes on: the publication, which has survived all kinds of crises, continues to function for 59 years as an intellectual beacon in this country.

Ten years earlier, Jason Epstein, who was born in 1928 in Cambridge (Massachusetts), grew up in Boston and studied at Columbia University in New York, had another idea: publish classics in paperback format, a preserve reserved for spy novels. , romance and crimes.

Then, great literature was given the lavish treatment of leather binding, in editions that a scholar like Epstein and the rest of his generation, better educated than their parents, could not afford.

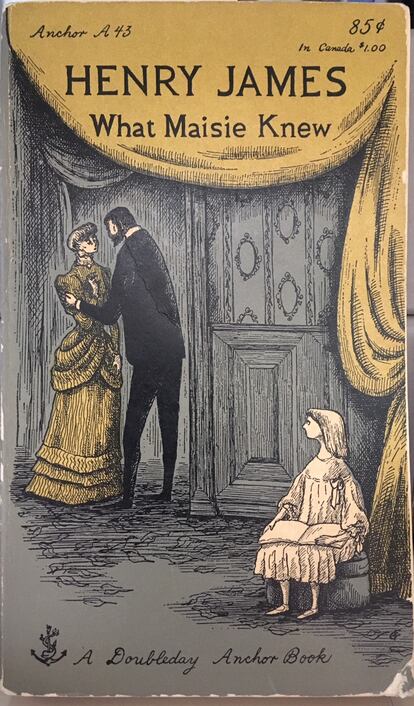

Thus, Anchor Books was born, publishing Edmund Wilson, Rilke, André Gide and Henry James at prices ranging from 65 cents to a dollar and a quarter.

“The covers were artistic, not crappy.

Many were signed by [Gothic cartoonist] Edward Gorey.

Epstein found that it helped,” writes Louis Menand in

The Free World.

Art and Thought in the Cold War

(The free world. Art and thought in the Cold War, Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 2021).

"This product was baptized as 'quality pocket book' to differentiate it from the traditional one."

By 1954, Anchor was already selling 600,000 copies a year, prompting rival Knopf to replicate the adventure and create Vintage.

Cover of the paperback edition of 'What Maisie Knew' by Henry James, illustrated by Edward Gorey for Anchor Books.

Many of those titles and their editorial spirit survive today at NYRB's sister publisher, which publishes classics of 20th-century world literature in paperback and Cartesian layout, with special attention to translated authors.

In the early 1980s, Epstein furthered his obsession with democratizing the classics by founding the Library of America.

Again, the inspiration came from Europe, this time from the Pléiade collection, from the Parisian Gallimard, a library of complete editions, aspiring to be definitive, of the great pens of French literature.

The American version, which turns 40 this year, offers readers a guarantee of quality, with its hard cover, bible paper, black dust jacket, white letters and a strip in the colors of the American flag.

From Mark Twain to Ursula K. LeGuin, from Jack Kerouac to William Faulkner, Mary McCarthy or Zora Neale Hurston, almost every great name in American literature can be found in his catalogue.

All these initiatives were undertaken by Epstein while working at Random House, where he arrived in 1958 with a contract that allowed him to pursue his personal adventures.

These never distracted him from his work as editor of Philip Roth, Norman Mailer or EL Doctorow.

To his persuasive capacity we owe, for example, the publication

Death and life of the great cities

(1961; in Spanish, in Captain Swing)

,

by Jane Jacobs, one of the most influential urban planning texts of the second half of the 20th century.

De Random retired in 1999, but still wanted more.

In 2003, he co-founded On Demand Books, which makes a contraption called the Espresso

Book Machine

, which, taking advantage of digital advances, enabled print-on-demand printing of a copy of a particular title within minutes when it hit the market.

The goal was to encourage self-publishing and eliminate the editorial stress of accurately calculating the print run closest to market reality.

A handful of these contraptions, which progress inevitably bent the hand, are still distributed by some bookstores around the world.

Epstein was married twice, to Barbara Epstein (until 1980) and to journalist Judith Miller (since 1993), who survives him.

He made his first steps as a writer, with essays on issues such as the 1968 Democratic Convention and the Chicago Seven, the publishing world or gastronomy.

He also wrote articles for

the NYRB

.

The magazine's website, which entered a new and still uncertain era after the death of Robert Silvers in 2017, has dedicated a large part of its cover throughout the weekend to remembering Epstein through some of his texts. for publication.

The last one, on animal suffering, came out in 2014. A year earlier, he wrote another, entitled

A strike and a beginning: that's how we founded The New York Review,

half a century after that dinner, which was improvised that same afternoon, when Barbara Epstein and Elizabeth Hardwick met by chance in the neighborhood they shared.

The article ended as follows: “I am still shocked to remember the completely unexpected chain of events that combined to make

The Review possible.

The newspaper strike that handed us the opportunity to do the kind of review Lizzie's article called for [Hardwick, who had published a piece in

Harper's

calling for a renewal in American literary criticism].

The chance encounter between Barbara and Lizzie.

The availability of Bob [Silvers].

The unspent advertising budgets of publishers [who had no papers to advertise in] and the ability of [Anchor Books distributor] Eastern News to reach the right readers.

The willingness of forty-five authors to complete their work on time, for which we do not pay them.

The duration of the strike.

That all of this happened at the same time still seems like a miracle to me in hindsight.”

That miracle on old newsprint is in mourning these days.

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/Z45E6KV7VJGUXAKJWH7VA4NJSE.jpg)