It is noon in the municipality of El Paso (7,500 inhabitants), on La Palma.

The youth team of the Atlético Paso soccer club trains between shouts in the municipal sports field.

The palm tree sky has dodged the

Celia

storm and it has dawned clear and cloudless.

Calm reigns on the beautiful island.

At least in appearance.

Just six months ago, the situation was different.

On September 19, at 3:02 p.m., the La Palma volcano erupted, in the middle of the Cumbre Vieja natural park.

The authorities decreed the urgent evacuation of some 5,000 people, and the affected residents had to leave with their personal belongings.

The most anguished night awaited them and 85 days of a nightmare that ended on December 14 with 7,000 displaced people, devastated 1,219 hectares and destroyed 1,676 buildings, 1,345 of them for residential use.

“El Señorito (referring to the volcano), when asleep, nothing,” Gladys Pérez, 65, tells Begoña, full of energy, the impassive owner of the La Botica bar, in the Llanos de Aridane (the main municipality of the island, with 25,000 inhabitants).

“Last night I was watching TV and the headboard started shaking again.

This demon is not over."

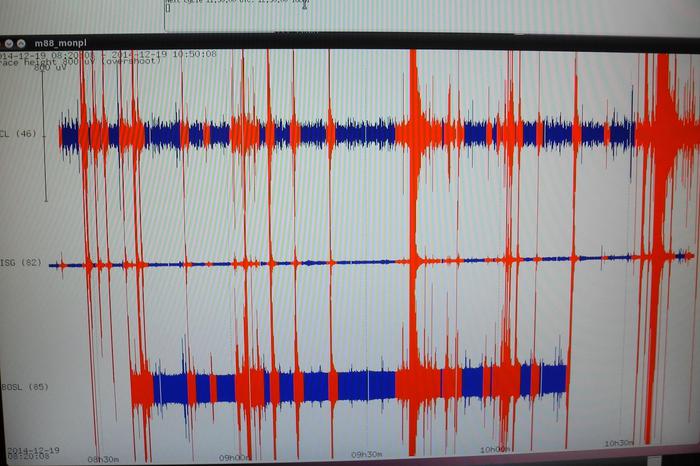

The eruption itself has culminated, emphasizes María José Blanco, director of the National Geographic Institute (IGN) in the Canary Islands.

"But the volcanic process continues its course within normality."

And this normality, she explains, includes among other aspects a seismicity "of low magnitude, less and less frequent and less and less felt by the population."

Because La Palma seems to have returned that characteristic tranquility.

But it is hardly a facade.

Estefanía Martín is the referent psychologist of the point of single attention to the citizen in the town of Argual (Los Llanos de Aridane).

She warns of the effect that the lack of aid can have on the population.

"Many people present pictures of anxiety, sadness and depressive symptoms," she explains in a telephone conversation.

“Especially those that still do not have a response from the Administration.

They have the impression that their pain is not taken into account.”

The administrations assure for their part that they are working against the clock to alleviate the situation of the palmeros.

"The key to these three months continues to be unity and work," emphasizes the president of the Cabildo, Mariano Hernández Zapata.

“Never has work been done so quickly and so effectively in any other catastrophe”, completes Sergio Matos, former mayor of Santa Cruz de La Palma and coordinator of Social Action in the Office for Attention to Victims of the volcano.

"There is much to do?

Of course.

But the balance is positive.

We have to push together."

More information

La Palma: the black trace of the volcano

The administrations had delivered until last Thursday 365.56 million euros in aid: 163.9 million in housing, 79.6 million for social emergency and 54.5 million to support employment and companies, self-employed and economic sectors, according to the report provided by the Government of the Canary Islands.

The service office has received 5,796 requests, the processing of which has already been initiated in at least 90.5% of cases.

The number of homes delivered is around a hundred.

But the damage is still very visible.

And those affected, too many.

Vicente Leal, the owner of the house closest to the volcano, in the palm town of Las Manchas.Samuel Sánchez

Cleaning

.

“All I want is to get my house back”

Fate and terrain have wanted Vicente Leal (60 years old) to be the owner of what is surely the closest standing house to the eruption, in the town of Las Manchas.

Barely 20 meters from the walls, a lava tongue serves as a reminder of the hell in which that paradise acquired in 1991 became for weeks. And six meters of height of ashes remind Leal himself daily of the work that remains for him to do. that this dwelling can once again be qualified as such.

"I fell in love with this land when I was little, when I accompanied my father on his walks in the area."

His work as a technician for the Administration and an expert in logistics and transportation allowed him to acquire it, and, slowly, he turned that wasteland and that straw man into a house with an adjoining studio.

“Look at the mulberry beams, 200 kilos each, that we climb one by one between two,” he points out proudly outside the house.

On September 19, like so many others, his life changed.

"At that moment everything fell apart: my life, my prospects."

He had left the company and hoped to turn the property into a tourist village.

"That was my life plan," he laments.

Las Manchas became the epicenter of the exclusion zone.

The area mutated into a dystopian scenario populated by hastily abandoned houses covered by a new unwanted tenant: the ashes.

A titanic effort has returned some splendor to this district.

Effort of people like Leal, who spends his days on the farm, removing ashes.

A cleaning job that he did not abandon during the eruption, especially to prevent the weight from causing a collapse.

"Whoever tells me that I won't be able to clean all this is because he doesn't know me," he says while posing proudly before the cameras.

The future, however, is again an unknown.

"I want my house back," she exclaims.

"That is clear to everyone.

But if I end up becoming another victim and the public authorities do not let me live there and I have to bequeath the house to the palmeros, what I do want is compensation for me and my neighbors according to the location and the enormous expense that we have had All these years".

And he concludes: “I am close to retirement.

I just want my children to be able to live without the disappointments of life that I have had to swallow."

Juan Carlos Rodríguez, palm farmer, in a destroyed banana plantation in the municipality of Los Llanos de Aridane (La Palma).

Samuel Sanchez

Agriculture

.

“The campaigns are beautiful on TV.

We're screwed here."

“We palm farmers have found ourselves in a situation that we did not expect: neither in intensity nor in duration.

The volcano has crushed us emotionally.”

This is Juan Carlos Rodríguez,

Juanki

, a 46-year-old “battler” farmer.

He lost 95% of the one and a half hectare farm he owned because of the ash.

But it is the bureaucratic obstacles and the decisions of political leaders that occupy most of his concerns.

Especially the water.

"The desalination plant that they installed has not served at all," he denounces in a cafeteria between El Paso and Los Llanos.

"Why didn't they do anything to install a pipe that passed through Fuencaliente, or in another area, which would have been cheaper and more efficient?"

The volcano swept away 370.07 hectares of crops.

Of course, the banana crop stands out: 228.7 hectares of unused plantation.

Banana cultivation occupies 43% of the 6,943.6 hectares of agricultural land in production on an island that is second in the Canary Islands for production, with 32.4% of the total.

In 2020, 144,302 tons of this fruit were exported.

That means revenue of about 135 million euros.

The Association of Banana Producer Organizations of the Canary Islands (Asprocan), chaired by Palmero Domingo Martín, demanded this week from the Minister of Justice, Pilar Llop, among other issues, that they be reassigned an area, at least equivalent to the one they lost , in order to be able to resume productive activity.

"We work hand in hand with the Canarian Government to recover the banana plantations", promised the president of the Island Council, Mariano Hernández Zapata.

But Juanki Rodríguez is pessimistic.

"The exclusion zone has been completely lost," he says.

Maybe 5% to 7% can be collected.”

He assures that he maintains the fighting spirit, but admits that the initiatives "look very good on television" when they are announced by politicians.

"But those of us who are here are screwed."

Eulalia 'Laly' Villalba, owner of El Bucanero, in Puerto Naos, poses in a park in Los Llanos de Aridane (La Palma).

Samuel Sanchez

Hospitality

.

"If we don't have help, many will be left behind"

Eulalia,

Laly

, Villalba (57 years old) is the owner of El Bucanero, in Puerto Naos.

Before the pandemic, this was one of the few venues that offered live music almost daily.

"To reopen after covid I had to invest all the savings I had then, since inactivity and humidity destroyed the interior."

Villalba saw how the turnover grew during the summer.

“We had fantastic forecasts for the winter.

I spoke with the tour operators and they told me that they were full.

And, suddenly, the volcano came.”

The accumulation of gases has made Puerto Naos uninhabitable six months later.

And, meanwhile, Villalba manages to pay the rent and the education of his daughter, already in the university.

"I survive as best I can thanks to the help of Cáritas and the Red Cross," she explains in a telephone conversation.

Not even the aids allow him to take off.

“Both companies and small businesses that are taxed by direct estimation have benefited from aid from the Government of the Canary Islands through the Chamber of Commerce.

But those of us who pay taxes by modules have been given very little aid.

We have filed an appeal."

La Palma has not recovered from the blow.

With just 30,680 overnight stays in February, the island collapses compared to 2019, according to data from the Ashotel employers' association.

Its occupancy rate barely reaches 27%.

"We are going week by week," confesses Carlos García Sicilia, owner of the Hacienda de San Jorge, in Los Cancajos Beach (Breña Baja, in the east of the island).

"Our main clients are German, and things are not going well," he explains.

"We started with covid, when we were leaving the volcano came, in March the war came... it's quite a complicated thing."

Laly

Villalba is a well-known person on the island.

And she wants to keep it that way.

“Many have left here,” she explains, “but I don't want to leave.

If we don't have help, many will fall by the wayside."

Lourdes Armenia López, from the Tierra Bonita Association, poses in El Paso (La Palma) on March 17.

Samuel Sanchez

Living place.

“When I close my eyes, I imagine the lava eating my house”

Lourdes Armenia López,

Meñi

(46 years old), lived with his 79-year-old father and his 11-year-old son in a house next to the road that linked La Laguna with Todoque.

She was evicted that September 19 and never slept in it again.

"I'm still going through very difficult times," she explains at her son's school.

López lived for rent, so she is barely entitled to aid from the Government of the Canary Islands scheduled for 36 months that will cover the difference between what she paid before the eruption and what she has to pay now.

The president of the Cabildo palmero, Mariano Hernández Zapata, assures that housing is "the main key and absolute priority of reconstruction."

Last week, the Canarian Government announced an additional aid of 30,000 euros for people who have lost their main home, to which another 10,000 euros of direct aid will be added by the Cabildo.

These two contributions will complement the 60,000 from the Government of Spain.

The rhythm, however, exasperates the clappers.

Meñi López was a caregiver, but she lost her job when the woman she cared for lost her house under the lava from the volcano.

She has found a temporary job in the Tierra Bonita association, created to manage donations from individuals.

“I have moved forward thanks to the support of the Red Cross,” she says.

And she confesses: "Sometimes, when I close my eyes, I imagine the lava eating my house... And I never saw the scene."

Mónica Viña, director of the CEIP La Laguna, in the new location of the center, in Los Llanos de Aridane (La Palma).

Samuel Sanchez

Education

.

“There are wounds among the students”

The volcano had no regard for schools.

Its lava engulfed the schools of Los Campitos and Todoque (Los Llanos de Aridane), which were rehoused in a school named Princesa Arecida.

Another third center, Puerto Naos, remains closed due to the accumulation of gases.

The center directed by Mónica Viña (51 years old) in La Laguna also ended up devoured by the lava flows.

All the classrooms were on one floor, within small blocks that communicated with open-air corridors, and it was a benchmark for educational innovation on the island, especially for its Emotional Education project - a compulsory subject in the Canary Islands since 2014. ―.

The school closed its doors on September 24 and succumbed in mid-October.

For this reason, Viña and her team set up a second CEIP La Laguna at the El Retamar Cultural Center in Los Llanos de Aridane, where they now teach 150 children.

"The children remember the previous center and assure that their other school was better, more beautiful", she recalls with a smile in the new facilities.

"There are wounds, also in the smallest students, who we usually believe are not so affected."

Among the good that misfortune has brought is the solidarity of other schools throughout Spain.

"We don't stop receiving letters, gifts, drawings," she tells excitedly while she opens boxes with correspondence that she gradually answers.

He also appreciates the work of the Ministry of Education, which "has put a lot of resources of psychologists and pedagogues" and has just announced that in the future, when the lava allows it and the new center is built, they will return to their old location.

"For us it is essential," she stresses.

"The life of the neighborhood cannot be lost."

Antonio Gabrieli, owner of La Cantina del Gladiatore, in Fuencaliente (La Palma).

Samuel Sanchez

Infrastructures.

"The cut of the road to Los Llanos has killed us"

Antonio Gabrieli is a Roman who has just turned 70 and who, despite the 18 years he has been in the Canary Islands, has not yet mastered Spanish.

In 2004 he left his textile company ("we wanted to live a new life") and settled in Mogán (south of Gran Canaria), where, with the help of his wife and his two sons, he set up the pizzeria

The Gladiator's Canteen

.

Seven years ago he visited La Palma, and decided to pack his bags and change his life again in Los Canarios (municipality of Fuencaliente).

Until September 19, its premises could be reached from the main urban center of the island (Los Llanos de Aridane) in just half an hour.

The cut of 2.3 kilometers of the LP-2 between both towns has turned this journey into a journey of at least one hour.

“At least I am working, there are people dying here.”

The lava reigns in turn over other key arteries, such as the coastal highway, which has lost a vital 1.6 kilometers to connect to the banana plantations of the southwest.

The cut of infrastructures and the closure of Puerto Naos “is going to kill the island”, he sentences.

Further accelerate your mix of Spanish and Italian

when he remembers the fine of 3,000 euros that Social Security has communicated to him that same morning.

A few weeks ago, an inspector showed up at the pizzeria while he and his wife were talking to a potential buyer of the premises, who they are trying to sell.

The official assures that Gabrieli had the premises open, with a client, and was not trading.

"The government takes you away, it doesn't help you," he explains indignantly.

"After two years of covid and one of the volcano, are you coming to fine me for something I haven't done?"

And he sentences: “There is no political will to fix things.

Only speak.

And meanwhile, the people here don't have a job: the place next door is under minimum, if they work one or two days it's already a lot”.

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber