Miquel Barceló, at the Elvira González gallery. INMA FLORES (EL PAIS)

The white light of the room is broken by the explosion of intense fuchsias, yellows, reds, greens and blues in the paintings exhibited by Miquel Barceló at the Elvira González Gallery (Madrid, until May 28), together with whimsical ceramics, jugs , mud that occupies one of the tables: they are “remains of the shipwreck”, he says, from a cooking and molding process that sometimes decides on its own the result or the final failure.

He poses for the photographer, but immediately runs away, Barceló always runs, and this time too, before we sit down in the gallery's office to talk about books, about his writing, about other compulsive vices.

More information

Miquel Barcelo: metamorphosis of a "weirdo"

Among the most entrenched is writing without wanting to write and, above all, without pretending to be a writer or publishing what he writes between trips, in waiting rooms, Air France journeys (to curse white people like himself who travel first to Africa on Air France flights), devastating dysentery that leaves him unable to paint but not to write, and always by hand, in notebooks that mix drawings and texts, like when he was a child.

The notebooks that his mother kept and he keeps now are full of texts and drawings, drawings and texts: he did the same thing he has continued to do as an adult.

He now writes in French because it gives him the distance that he does not find in Catalan, where the propensity for obscenity, insult or irreverence would make those pages useless.

And furthermore, "since I'm not a writer, I can write in whatever language I want", although his native Majorcan would fill his notebooks with the scandalous vitality of the language of the street, with abrupt insults and with the impetus of a village boy , born in Felanitx 65 years ago, a vocational nomad between Paris, Mallorca and multiple places in an Africa that he can no longer visit as often as before.

From there comes —from its lands, its animals, its vegetation and its human swarming— material for a painting that is physical segregation, like when he discovered as a child while he was playing, always playing, what painting was.

Drop a spit on a sheet of coated paper, release a drop of Chinese ink and start blowing to create forms "from this accident": "All life the same drive", create figurations with a brush from a unruly mix.

He could even serve at some point to dedicate himself to "counterfeiting banknotes": classmates admired the exact copy of the bill... on one side only.

"I was anguished

fer de soldat

[doing the military] and having to earn a living."

The French that he continues to use for his notebooks he learned on his first trips to France, in 1981. Today he prefers that the texts of his catalogs —like that of this same exhibition,

Kiwayu—

not be commissioned from experts or “mercenaries”, he has preferred select some wonderful pages from his diaries (translated from the French by Enrique Murillo) and a story from an old friend, Paul Bowles.

“Written at the time I was born, or around there”: around 1957.

Barceló does not paint what he reads, but without his readings he would not paint as he does: the omnivorous reading is part of the very formation of painting, as is the diving he practices in Africa and Mallorca morning and afternoon, without fail, as a disciplined fisherman of underwater images.

Barceló's genius is made of disobedience, spontaneity and raw life, hardened in books as raw material.

For this reason, when he paints in the studio, convinced and dedicated, he has to make sure he “doesn't waste time” with writing, and he writes here and there “Don't write, don't write”, in order to continue painting without getting lost.

Without that literate, anarchic and slimy culture there is no painting.

The only time he taught, in Bamako, in Mali, he did not ask the boys what they had painted, but what they had read: "If you haven't read anything, you will never be an artist."

Without the 14-year-old boy having read Kafka in

The Metamorphosis

(in the Alianza Pocket Book edition...), Barceló would be someone else, and it would be worse: “Discovering Kafka and Rimbaud was as important as discovering Miró and Miró. Picasso”;

like the discovery at the age of 12 of Poe's stories: “he changed my way of being in the world”.

With Kafka in a town in Mallorca, he began to see "the world in a different way forever."

That is why he found her mother crying the day she had already read the book on her way back from school, and thus discovered that Miquel had ceased to be a child.

Some of his judgments are just as quick and categorical: the diaries of Adolfo Bioy Casares, titled

Borges,

they are “a masterpiece” that has received incomprehensibly little attention.

It can be taken "anywhere at any time", because the spark of intelligence and evil (of Borges, above all, "very bastard and very incorrect") are assured, a "bedside book" and a "great book of our time”.

To remember other recent readings, Barceló opens his mobile phone and slides with his finger the covers and covers of books he has read on paper when he is in Europe and on his mobile when he is in Africa, until the titles he is looking for by Claudio Rodríguez, by Gil de Biedma, but also Ida Vitale, the lifelong Cavafis, César Aira more recently, together with Piedad Bonnett, or Ishiguro, although he has also returned to the absolute classics and has reread all of Proust, including the new biographies and the revelations of the maid,

Chirbes

Sometimes it seems that he spends more time reading and writing than painting —”noooo: painting is very demanding”—, although the list of new and old books that have passed through his hands is endless, including writer's diaries read with fondness as an expert: those from Chirbes “are very good”, he reads everything that Iñaki Uriarte publishes, and even aspires to recognize him in any street (“I don't know him, but almost as if I knew him”);

in fact, he liked “even those from Marsé” because he “is like me: he does nothing but swim and write”, in his case swimming and painting in Kiwayu.

Miquel Bauçà, "is very geek, very geek", and Gabriel Ferrater, "great" in his Catalan literature course, although the origin of everything is in Pla and

El quadern gris

, and in the tradition of Chauteaubriand and Stendhal because Stendhalian is their way of being in the world.

And there he also continues to reread Pessoa and his heteronyms, the

Book of Disquiet,

but also the heteronyms Álvaro de Campos and Alberto Caeiro.

Por Pessoa went with Mariscal to Lisbon to paint in the 1980s, a little before he became known as a character in a book by his “best friend” for a time, Hervé Guivert, who died of AIDS in 1991 while Barceló painted his agony (“having a friend that you know is going to die is fucked").

In

The painter with the red hat

, a character in the book is Barceló made of fiction with hardly any fiction, “I live in Corfu, in Burkina Faso and New York, but it's me, a little changed”.

Barceló is still that boy with his hands in the mud, in the brushes, the canvases, the ceramics and also his notebooks.

"Literature is nothing more than the correct use of language," he reads aloud on page 71 of the

Kiwayu catalog

.

The phrase is from Evelyn Waugh, he reads it up to three times, but neither he believes it nor I believe it.

I ask him where the “serene savage” in his painting is there, as it was once called, and the

demarre

betrays him: “Each one decides what is correct, of course”.

That is why he assures that “important things” are not counted in the newspapers.

Compulsive reading is no longer the habit it was.

After the mess of an ex-partner —she organized the library books by format…—, she couldn't find anything, she read randomly and sometimes she bought again books that she already had, but she couldn't locate them.

Today the order has returned to the alphabetical law: “I like the order, but I am not able to put it myself”.

Suddenly he stops resisting and admits that yes, writing can be an instrument of order: “I clarify myself and order myself in disorder”, and perhaps for this reason he has “a very bad relationship with authority”;

He is not very good at obeying either and almost always "dispersion" is his natural way of acting.

In painting little by little the palimpsest gains meaning, but not in writing, which is pure dispersion or pure “digression”.

When I tell him that I do take what he writes seriously,

he jumps overboard: "What do you want to propose to me, that I act as a reporter around the world?"

Done.

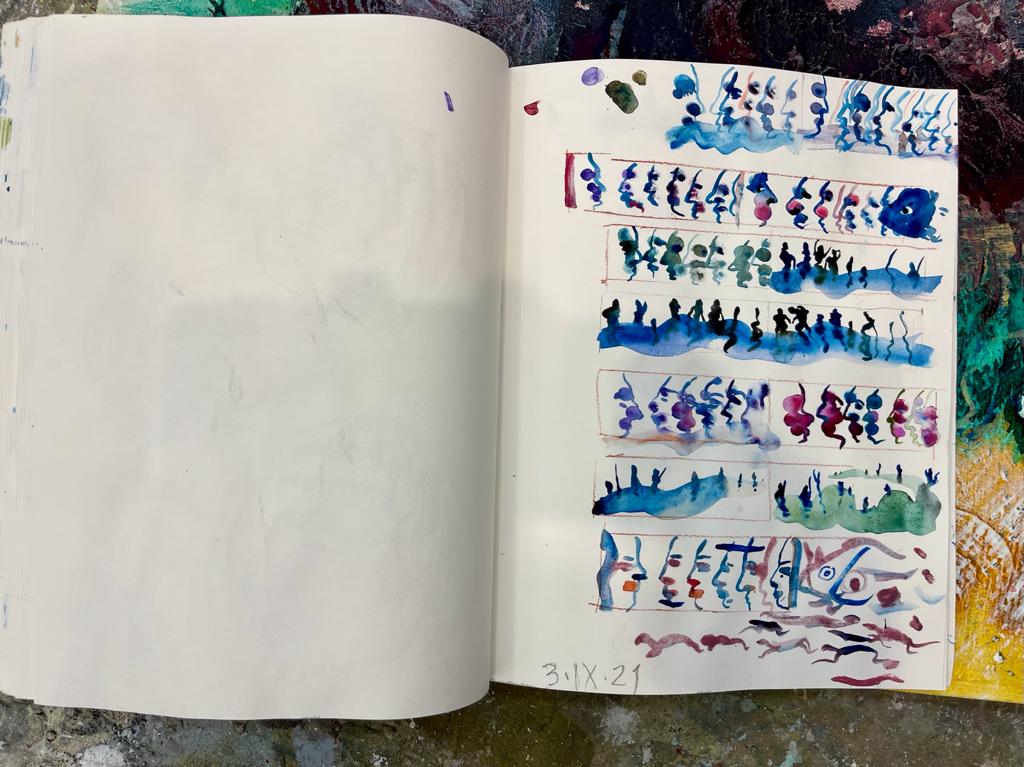

The illustration for the Letters to the editor of EL PAÍS

Barceló immediately agreed to draw and paint tests when we proposed illustrating the Letters to the director in the paper edition of EL PAÍS.

We wanted to place the section on the same pages as the editorials and the masthead, and we also wanted the reader to identify its own place through an illustration.

She sent out as many as two dozen proofs, all lively and interactive, happy one-liners that talk to each other and talk to the viewer.

In the end, we opted for the one she has been illustrating for months in the section.

It was Barceló himself who suggested changing them over time.

It could happen any day.

These are some of the discarded samples.

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber