Art never comes out of the trenches unscathed.

At the end of the First World War, German painting moved away from the excesses of expressionism to adopt a more cold, distant and austere style, which aspired to reflect the social reality after the end of the war.

The movement, baptized as "new objectivity" in an exhibition opened in Mannheim in 1925, opted for a stoic figuration that bordered on the inexpressive, a possible reflection of the culture of shame that emerged in Germany after its defeat.

Art was filled with portraits of resigned characters with empty eyes, lost in the midst of the absurd and dislocated landscape caused by the war.

A multidisciplinary exhibition at the Pompidou Center in Paris now reviews, through an endless selection of 900 works and documents, the official history of the twenties in Germany, almost always subject to the golden legend of the Weimar Republic, which the museum Parisian now demystifies with a mixture of caution and courage.

The most daring thesis in the exhibition, which can be seen until September 5, is that there was no clear break between the twenties and the thirties.

“Those two periods are often opposed, when it was a more fluid transition than is believed.

There was no dry cut”, confirms the curator Angela Lampe.

In another daring gesture, the commissioner decided to paint the last wall of the route a dirty brown reminiscent of the first Nazi uniform.

In this way, she evokes the fateful end of this story.

"Even so,

it is not appropriate to make a teleological reading.

The artists who began to paint in the year 1925 could not have known what would happen in 1933”, he clarifies.

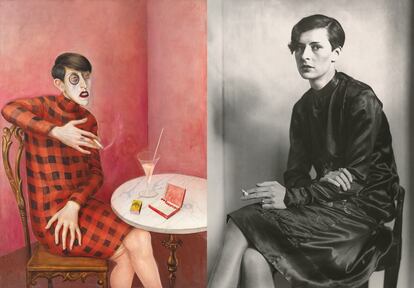

On the left, the oil painting 'Junger Mann' (1921), by Anton Räderscheidt.

On the right, 'Maler' (1926), a portrait of the painter Anton Räderscheidt by the photographer August Sander, who seems to take up the features of the model in his painting.Galerie Berinson / Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur / Sander Archiv © Adagp, Paris , 2022

Despite the fact that the Nazis burned the movement to the stake, branded its creators as "cultural Bolsheviks" and forced its greatest painters, such as George Grosz or Max Beckmann, into exile, some of its stylistic traits survived.

The purification of expressionism carried out by this school seems to dialogue with Adolf Loos' theses on the "immorality" of ornament.

Without going any further, the poster for the 1925 seminal exhibition was illustrated with an inexplicable neoclassical-style building, which would have such a fortune a few years later.

Some of its members continued to work under the new regime, such as Christian Schad, despite never openly supporting it, while Weiner Peiner, included in that first exhibition, became an artist admired by the Nazis: one of the rural landscapes of the,

depositories of German essences, was given to Hitler as a gift when he came to power.

However, most of its members belonged to its left wing, which aspired to reflect the poverty and exclusion that galloping industrialization had caused in the country.

The exhibition reflects the fascination with Fordist productivism after the injection of US capital in post-war Germany, which enriched the very companies that would later finance Hitler's election campaign without question.

But it also leaves room for the losers of that system, workers, beggars, gypsies and other outcasts who in some paintings abandon the anonymous mass and express something similar to grief.

most of its members belonged to its left wing, which aspired to reflect the poverty and exclusion that galloping industrialization had caused in the country.

The exhibition reflects the fascination with Fordist productivism after the injection of US capital in post-war Germany, which enriched the very companies that would later finance Hitler's election campaign without question.

But it also leaves room for the losers of that system, workers, beggars, gypsies and other outcasts who in some paintings abandon the anonymous mass and express something similar to grief.

most of its members belonged to its left wing, which aspired to reflect the poverty and exclusion that galloping industrialization had caused in the country.

The exhibition reflects the fascination with Fordist productivism after the injection of US capital in post-war Germany, which enriched the very companies that would later finance Hitler's election campaign without question.

But it also leaves room for the losers of that system, workers, beggars, gypsies and other outcasts who in some paintings abandon the anonymous mass and express something similar to grief.

The exhibition reflects the fascination with Fordist productivism after the injection of US capital in post-war Germany, which enriched the very companies that would later finance Hitler's election campaign without question.

But it also leaves room for the losers of that system, workers, beggars, gypsies and other outcasts who in some paintings abandon the anonymous mass and express something similar to grief.

The exhibition reflects the fascination with Fordist productivism after the injection of US capital in post-war Germany, which enriched the very companies that would later finance Hitler's election campaign without question.

But it also leaves room for the losers of that system, workers, beggars, gypsies and other outcasts who in some paintings abandon the anonymous mass and express something similar to grief.

“It is often opposed to the twenties and thirties, when it was a more fluid transition than you think.

There was no dry cut, ”says the commissioner

The exhibition maintains that, in the painting of the 1920s, everything became a still life, including humans.

Man became mere architecture, a fragile building that was no longer safe from bombs and demolitions, like those old neighborhoods razed during the first wave of rationalism in cities like Frankfurt or Cologne.

From then on, the human being will be an interchangeable and disposable object, just like Marcel Breuer's removable furniture pieces.

In the art of the time, the personality or psychology of the model no longer matters.

Only his profession and his social category count.

The artists will classify the population as if they were entomologists.

The best example is that of the photographer August Sander, who occupies a central space in the exhibition,

Sander undertook a monumental project,

Twentieth-Century Men

, with which he wanted to x-ray all the social groups of the Weimar Republic, in a great national taxonomy that ranged from entrepreneurs to peasants, from writers to madmen, from political prisoners to the first Nazis in uniform.

The communicating vessels between photography and painting are another

leitmotiv

of the exhibition.

It is obvious that the first discipline influenced the second when moving away from artistic subjectivity.

"Although it was later understood that photography is also a construction, then it seemed to be an art closer to reality than painting," explains Lampe.

In reality, that influence was mutual.

This is demonstrated by some of Sander's compositions, which seem to be traced from Otto Dix's paintings.

For example, a 1931 snapshot starring a secretary could be inspired by Dix's well-known portrait of journalist Sylvia von Harden five years earlier, in which a relative misogyny can also be discerned today.

On the left, 'Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden' (1926), by Otto Dix.

On the right, 'Secretary of the Westdeutscher Rundfunk in Cologne' (1931), by August Sander. Center Pompidou / Die Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur / Sander Archiv © Adagp, Paris, 2022 © Adagp, Paris, 2022 /

That is another of the lessons of the exhibition, dedicated to a style that sold as omniscient neutrality what now seems to be a growing taste for caricature and veiled criticism of a society immersed in a brutal transformation.

The Berlin of the twenties went down in history as a paradise of debauchery and tolerance, as the capital of the homosexual subculture that reigned in its 170 nightly cabarets and that of women's liberation, which won the right to vote in 1918. The portrait made by the Pompidou is much more ambivalent.

“All that existed, but also the other side of the coin.

Some artists were afraid of that emancipation, of that confusion of genres, and reacted with violence”, Lampe maintains.

The exhibition exemplifies it with pictures that collect sexual crimes that served "to kill women symbolically", according to the curator.

Dix himself captures, in his infamous portrait of jeweler Karl Krall, all the homophobic stereotypes of the time, which used to equate homosexuality with hermaphroditism.

The exhibition exposes this canvas next to a 1922 film that collects the thesis of the doctor Eugen Steinach, who believed that this sexual orientation was a transgression of the biological order that surgery would be capable of correcting.

In another of his best-known paintings, Dix portrayed Anita Berber, a bisexual dancer and junkie, with her face consumed by sin, as if it were an omen of her death, a few months after her, at the age of 29. .

Her semblance seems anything but a celebration of the amorality of that transgressive character.

At the end of the exhibition, a semi-transparent wall communicates the beginning of the tour with the last room, dedicated to the exhibition that the Nazis organized when they came to power in 1933 to denigrate and bury the movement.

Only eight years have passed, in which the new objectivity has gone from being the height of modernity to becoming the prelude to degenerate art.

However, it will never die completely.

It will influence successive schools of inexhaustible figuration, from Balthus to the latest batch of African-American painters.

Without taking into account its roots in socialist realism, which reinterpreted its flat surfaces, its simple forms and its didactic spirit, the same that would permeate Brecht's epic theater, the "utilitarian" poetry of the interwar period or the so-called

Zeitoper

or “current opera”.

That is, without a doubt, what Goebbels did not see coming.

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/UR4QR6POJFBHPDM7OWJOJXPHDI.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/KRD2LI5IMVFG3IDDWM2ZAAPS2I.jpeg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/IGZ7GOCXZ5GUPAQ2HWGK6Z76BU.jpg)