Spanish music looks so much at the navel that it has lost the ability to build new meanings.

What is most worrying is that this is happening now, when times are more alarming than ever.

Times in which society is in a fractured situation due to a new economic crisis and eternal job insecurity that affects all possible vital developments (emancipation, family construction, retirement, leisure, equal opportunities...) .

Times in which the extreme right has established a violent discourse against the weakest and that has already reached the institutions.

Convulsive times in Spain, and Europe and the world, true, but also times in which, looking at our land, Spanish music does not react.

Perhaps people like The Clash, an unusual and combative group that never gave up an ideology and a commitment to the present, are beginning to be needed in these times.

And perhaps it is necessary to have a group or artist like this because the present is more urgent than ever.

Much more than nostalgia or fantasy.

It is urgent everywhere, but it is convenient to focus on Spain, which touches us much more closely.

British historian Tony Judt said in

On the Forgotten Twentieth Century

that "the recent past may be with us for a few more years."

He was right.

The past continues, and not precisely because of the fire that bands like The Clash awoke.

Follow the past of neoliberalism, intolerance, xenophobia, homophobia, ultra-conservatives, religious arsonists... If punk is already a vague memory of the past -and The Clash a poster with which we once decorated the room-, do not it is the context that propitiated all that musical movement, as ephemeral and chaotic as it is disruptive.

As is well explained in the book by the philosopher Alberto Santamaría,

A place without limits.

Music, nihilism and politics of disaster in times of the neoliberal dawn

: “The 1970s is the moment in which, it seems, a silent explosion in the economic and political spheres was unleashed, and our current situation is nothing other than an incessant rummage in the rotten footprints of that animal that came out of the cage in that decade”.

The animal is more alive than ever in 2022. It is enough to pay attention to the news any day to realize it.

And the least striking thing about that animal is, in the end, the most difficult thing to fight: the triumph of neoliberalism.

It is on this very complex issue that I want to focus.

In his very interesting essay, Santamaría explains it very well when he says that, in order to stabilize his story, neoliberal policy needed to “immunize” the market from alternative and democratic currents, from the most transgressive ideas.

That is, to form "a shield against social demands."

And this has been achieved "by reducing the capacity for political influence that society exerted from the street, from the social and cultural conflict."

Nowadays, success is so embedded in everyone's head that the possibility of being something better has been lost: being someone transcendental.

Even more so in these times in Spain.

Culturally, the answers are timid and scattered, while still being interesting, but they are always inconsistent.

Musically, things are worse.

The great bulk of Spanish music seems absorbed by the neoliberal triumph itself and, with it, its entire audience.

It does not seek conflict, it does not seek to create spaces that allow broadening political or economic notions.

Ultimately, you don't feel like you have to make a commitment to the present.

With the present in many areas, but above all in the most defeated: the political-economic.

It is not that there are no musicians and bands that include messages in the face of the situation, but a true combative reference is missing in this regard, as The Clash were with all the consequences.

Joe Strummer and Co.'s group represented a passion for resistance.

Because it is always possible to resist.

Currently, there is no action.

Philosophy is missing.

Ethical lack.

Disruption is missing.

And even lack self-destruction.

As Santamaría writes: “Punk did not want to be the solution to anything but rather the self-destructive dramatization of a time of crisis”.

Our time of crisis, in full digital domain, consumer lives and hyperconnection, is very different from that of the seventies, but the great cultural battles against neoliberal politics are still in force.

Perhaps more than before because they have been greatly blurred and become more complex.

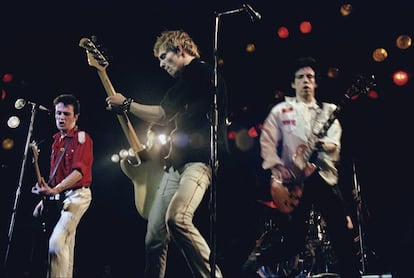

Joe Strummer, Paul Simonon and Mick Jones at a The Clash concert in London in 1979.Photo: Getty

The columnist for

El Confidencial

Esteban Hernández published an article this week in which he reflected that "success acts as a legitimizing factor, and today more than ever."

Entitled

The renaissance of the gafapastas: how they have managed to dominate the new cultural scene,

Hernández wrote that the new form of distinction was now in what was popular and successful.

And he gave the examples of Rosalía, C. Tangana and Chanel.

It is possible, but it should not be forgotten that all of them are issues that cause a lot of bile on social networks.

From one side and the other.

Also in the bars of bars and after meals with friends.

There is no middle ground with them.

They are admired or hated.

And, meanwhile, any possibility of reflecting on the value of his work is lost, let alone on other more complex aspects.

To tell the truth, it happens with many more cultural and other political and social issues within this polarized (and interested) existence in which we are immersed.

Therefore, this supposed distinction ends up being reduced to a drunken brawl in a bar.

The two sides seek to distinguish themselves like two peacocks in a sad corral.

Nothing more.

The problem is not that success is legitimizing and what is popular is now

cool,

as it used to be to come from England, France or the United States or spend the summer in Formentera or Benidorm.

The problem is that no one wants to end success.

All these cultural battles focus on tastes, aesthetics and life preferences, but never on what success is or on the system that supports it.

As the writer Javier Pérez Andújar said: "Many care about cultural battles, but few really care about culture."

In this sense, many care about success, but few, very few, really, care about the system.

And in the neoliberal system there is failure.

Much failure.

Both Rosalía and C. Tangana come from the alternate world.

They are musicians made from the bottom up and not the other way around.

No large multinational has controlled its steps.

It is the multinationals that join in their steps and they benefit from their alliances.

They have immense merit because, in addition, they have proven to be very good businessmen.

The latter today is almost more important than releasing good albums to maintain success.

The rest of the musicians can look at them with admiration or envy, but almost none can do better in such a short time.

The problem is that these referents, coming from their own margins, face nothing more than their own artistic growth.

And we can say this about the vast majority of musicians below them, which is all of them today.

Both Rosalia and C.

Tangana and the name of the artist that you want to put in the world of pop, rock and derivatives, not only want to be part of the system, but would love to reach the top of it.

What is the problem?

None and maybe all.

Because no one seems to stand up to the system or fight it or, paraphrasing Santamaría, self-destruct it.

They could have been better or worse, but The Clash embodied the spirit of an era and a real battle.

A very important battle: the battle against the neoliberal system, which allied itself with some wild ideas on the right.

A system that was emerging in the seventies and now in 2022 seeks to dominate everything, including our desires.

Because the system is inside tours, festivals, record companies,

streaming platforms,

marketing... and the musicians themselves.

And, of course, of his public.

The counterculture was always a response to the dominant culture, also to the established system.

Boredom, and not another urgency, was the inducer of the first adolescent culture back in the fifties and sixties.

And, from then on, there were times when the counterculture, beyond the denial of official art, wanted to overthrow conventions, fight against social pressure, create new spaces of freedom and propose its own political and philosophical language.

The countercultural, more than avant-garde, were the uncontrollable demons of a system that wanted to put an end to dissonance.

And, as stated in Santamaría's book, there is nothing better to end dissonance than to absorb it, empty it.

It was achieved: the counterculture was emptied by commodifying it,

The present has never been so reminiscent of an old past.

And, with a few exceptions, the role of music today can be regretted, but, deep down, the role of all of us should be regretted.

Hopefully some The Clash to shake us all.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/XSO4XYYIOJGKNPSUBHUGGDBMFU.jpg)