When we were happy and we didn't know it

is the title of the last book by the Colombian writer Melba Escobar and it is the phrase that Gabriela Arriens heard so many times in Venezuela.

"That is said a lot there, a Venezuelan reads that title and it seems familiar, of course," says Arriens, who has lived in Barcelona for nine months.

In her country, she owns a hotel in a tourist area, but her lack of clientele led her to emigrate.

Her daughter, Valeria, who left years ago to settle in Malaga, paid for her plane ticket.

Escobar (Cali, Colombia, 46 years old) wrote in 2020 a journalistic chronicle of the daily life of Venezuelans, the solemnly poor and the middle class that lost almost everything.

When we were happy and we didn't know it

(Ariel) has just arrived at Spanish bookstores.

Very diverse voices appear except the official ones of the Nicolás Maduro regime, who did not want to attend to it.

Escobar made four trips to Venezuela between 2018 and 2020 in which pain, corruption, ingenuity to survive and hope appear, something that most do not lose.

“When children die of malnutrition”, reflects the author, “when there are no medicines to treat diseases, when there are extrajudicial executions of which no one will ever say anything, when a month's salary is enough for a bag of milk and a tray of chicken, we keep thinking about bathing in hot water, about eating with cutlery.”

More information

Venezuela: the literature of chaos

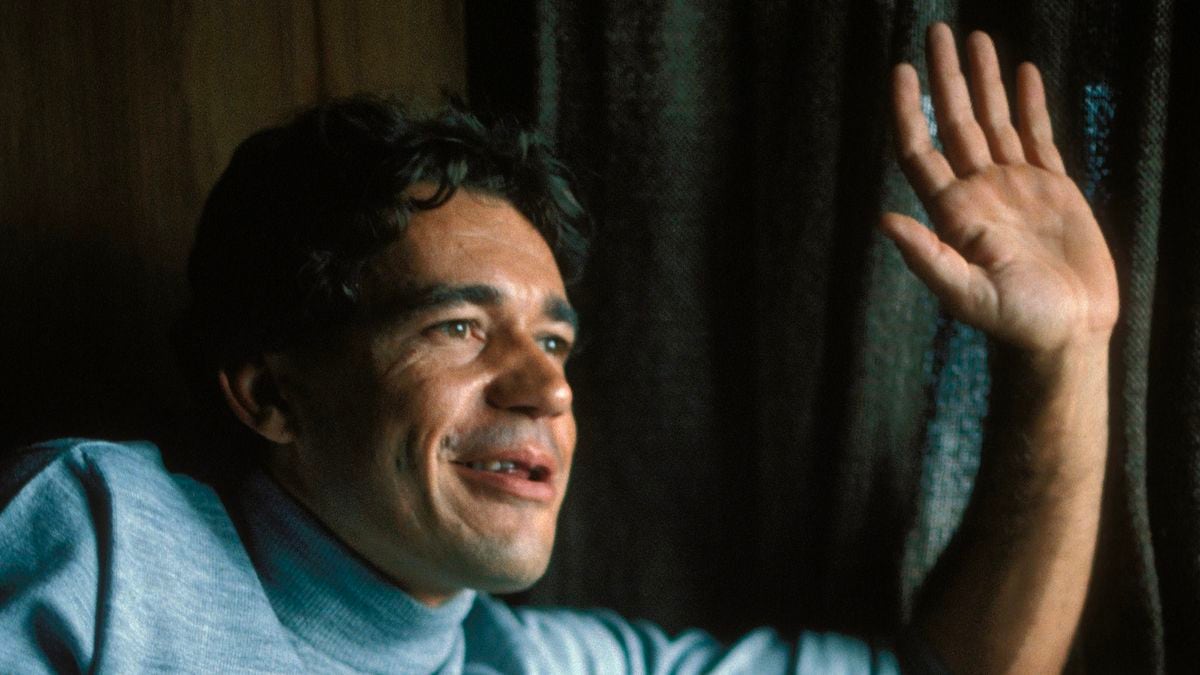

The writer Melba Escobar.MASSIMILIANO MINOCRI

EL PAÍS proposed to Escobar, who lives in Barcelona, a dialogue about the book based on testimonies from the large Venezuelan community in the Catalan capital.

Around a table in a Venezuelan restaurant in the Eixample district, devouring plates of fried fish, Arriens, his friend Daisy Ñáñez and his children met.

The last time that Ñáñez set foot in her homeland was nine years ago, there she still has one of her sisters: "She says she shouldn't come back, that I won't like what I see."

One of those interviewed by Escobar tells something similar in her work: “My mother-in-law lives in Chile and would like to return, but for her health it is better that she stay there.

Also, if she comes back, she won't know where she is.

The country she knew does not exist, she could not take a bus again to visit her friends, get on the crowded subway, go down to the corner to drink coffee like before, go out at night”.

Javier Cárdenas, 29, was suggested by some acquaintances to come to Barcelona to work as a delivery man, and he did so at the beginning of this year: “Here you can do something as basic as buy what you need, it is not possible there, the prices are very bad, and besides, you get to help your family”.

As a

rider

, Cardenas

He was friends with Joan Moncada, 24 years old and a Law graduate in Caracas.

“As a lawyer it is not enough for you to live, no matter how many hours you do.

In Spain you also work 12 or 14 hours, and you can't stop, but it pays off financially," says Moncada, emphasizing "the quality of life and security" of his adopted country, which he also bears in mind every day.

The straw that broke the camel's back, which made her leave Venezuela, was a violent robbery that she suffered.

Escobar reveals what happened to Daniel, one of the book's protagonists, shortly after he wrote it.

Daniel was the journalist's driver on one of the trips.

One night, driving drunk, he scratched a vehicle.

The owner shot him to death.

Juan Carlos González (left) from Venezuela, and Javier Mantilla from Colombia, wearing a cap, in Barcelona.MASSIMILIANO MINOCRI

Alberto González arrived in Spain in 2019 fleeing from the police.

He participated in one of the opposition demonstrations and they went to look for him at home, but he was not there.

His mother warned him.

They had already imprisoned and tortured his friends, and he decided it was time to leave Venezuela.

He is a delivery man and talks with his childhood friend Felipe Rodríguez in front of the Sagrada Familia, the usual meeting point for

riders

Venezuelans, the largest group in this sector.

Rodríguez migrated to Peru at the age of 17, where he washed cars and was a street vendor of lemonades, and for this reason a passage from Escobar's book in which a Venezuelan teacher who went to Peru calls her family to announce that she had managed to buy a pot to make rice: “At almost thirty years old, it is the first time that he manages to buy something with his salary”.

Surviving on salaries that barely allow you to buy a bus ticket takes a psychological toll.

“Mental health is being able to buy a flannel [shirt], have a beer, go to the beach, that is also mental health,” says a teacher interviewed by Escobar.

"If in addition to not being able to do any of that, you can't even pay for transportation to get to school or put food on the table, then I would have left too."

Being able to have a few beers on the beach and rest on Sunday, instead of spending it queuing to fill up water or gasoline drums in depressed places like Maracaibo: that is a luxury, says Cárdenas, that he can afford in Barcelona.

A carton of milk or some shoes

Rodríguez confesses a chapter of his life that is difficult to forget: the first time he went to a supermarket in Spain and discovered that he could buy food at affordable prices: “Now in Venezuela you can find everything, imported, but at prices that only a privileged few have access" There you have to choose between buying a carton of milk or some shoes", continues Rodríguez, "here, on the other hand, I can buy both".

Juan Carlos González, Venezuelan and delivery man, has a snack on a bench with three Colombian compadres while they wait for the next order.

Relations between Colombia and Venezuela, neighboring countries, are one of the most important sections in Escobar's book.

Javier Mantilla is from Bucaramanga, near the border, and he welcomed several Venezuelan families fleeing from hunger, now his friends, into his house.

Another Colombian adds that some of his acquaintances were murdered by Venezuelans.

That's because from Venezuela, adds González, “the honest and the one who steals marches”: “In Venezuela they kill you for a kilo of rice.

That is why even criminals emigrate.”

“No offense intended, but for us Colombians were the ones who came to pick up our garbage,” a Venezuelan acquaintance told Escobar.

"Now we Venezuelans are the ones who collect the garbage," adds González.

None of the interviewees considers returning to live in Venezuela.

50% off

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber