When a historian approaches writing an autobiography, it goes without saying that the result will embody the combination of the personal story and the general story.

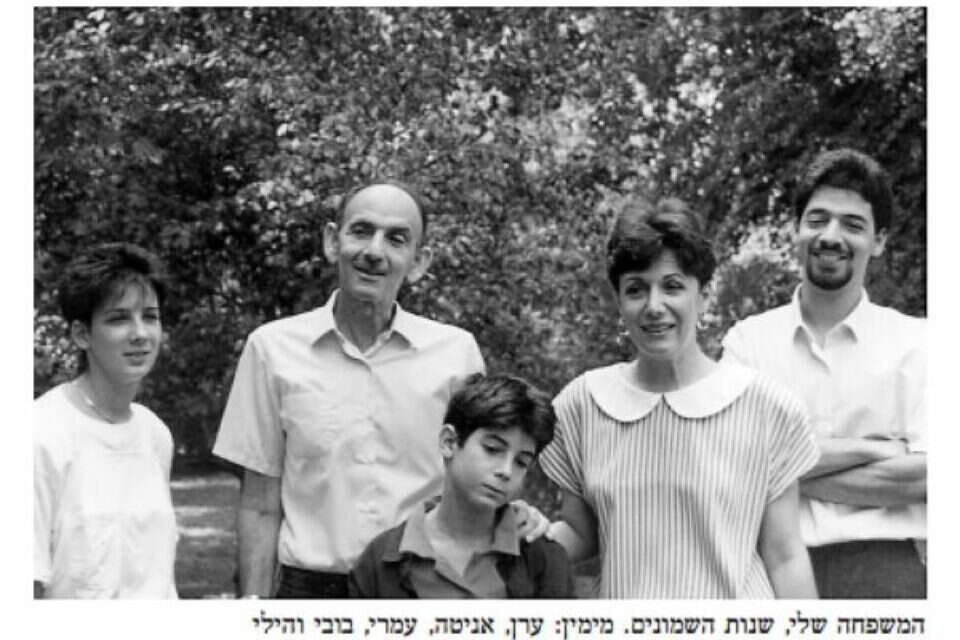

If it is an expert historian of Zionist history like Anita Shapira, whose count of years is close to the count of years of the state established by this movement, then the expectation of one piece, which interweaves the life of the individual in the nation's tract, is sharpened.

The result, it must be admitted, is not uniform.

Paradoxically as it may sound in relation to someone whose profession is to describe the historical processes of a collective, it is precisely the personal parts of "this is how it was," those in which Shapira removes from herself the heavy responsibility of writing history for all of us, that arouse the greatest interest.

Perhaps the explanation lies in the simple tone and preparation that blows from the personal descriptions, in contrast to the moments when the author tries to become the collective voice of the political camp that she often explored.

And perhaps simply because little Anita's personal story - born in Warsaw before the Holocaust, miraculously saved after her mother handed her over to a convent and adopted by another Jewish family at the end of the war - is so touching.

The opening of the first episode, in which the scene of the acquaintance at the end of which it will be decided whether the little girl left alone in the world will stay with mother Rosa and father son, is also overshadowed by shadows ( The reader's eyes and does not let go.

It is powerful and powerful from ten volumes of dry history and from any thick-bellied research.

Even in the sequel to "That's How It Was" the glimpses into Shapira's soul are more interesting than the episodes in which she tries to keep Passon and present a more formal and reserved appearance.

However, it is noticeable that this preparation is not easy for a notebook, and she herself knows it.

"Some people spill over and some people gather, who do not like to share their experiences," Shapira diagnoses, and immediately admits that she belongs to the second type.

Nevertheless, emotions are shared here and there even when she goes to detail her professional pursuits, and it's good that way.

Without them, navigating the tangle of petty politics of the departments that make up the Faculty of Humanities at Tel Aviv University would have become too tedious.

Shapira insists at length on the writing circumstances of her main books ("The Disappointed Struggle" devoted to research on Hebrew work; "Berl", Berl Katzenelson's biography; "Aviv Khalado", Yigal Alon's biography, etc.) Saves the mines on which she walks and opens a small window into the craft of biographical creation, which usually stays away from the public eye.

The first page is by far the most difficult to write, she declares, and does not forget to speak in praise of colleagues and interviewees, who helped her make it through the first pages, and those that came after them.

Her testimonies, which touch on worlds that have already disappeared, carry a special value.

Such is, for example, the story of Shapira's visit to Poland in 1986, and a description of a variety of emotions she experienced when she first saw the place where she was born and from which she immigrated to Israel decades before.

"I was happy for the Poles," she writes with unjustified directness.

"Poverty, misery, abandonment, repressive rule seemed to me a worthy revenge on Polish anti-Semitism."

At the same time, her impression of the contacts with the Poles, intellectuals and just ordinary people, reveals completely different feelings towards Israel.

Fulfilled the intellectuals (she attributes their positive attitude towards the Jewish state to their opposition to the Yaroselsky communist administration, which boycotted Israel on Moscow's orders), but ordinary citizens also found, according to Shapira, an interesting way to express their sympathy: In Warsaw, and people happily pointed to the lobby of a nearby hotel as the site of the assassination and marveled at its "clean" execution.

On that occasion, her group of Israelis also visited the extermination camps, long before such journeys became commonplace.

For some reason, when it comes to remembering this, Shapira skimps on words and only mentions that she erected a "wall in the form of emotional drift."

This wall apparently cracked while attendees finished one of the ceremonies in the song "Hope."

A thin rain of ice fell on them, a bone-freezing wind whistled, and their throats suffocated.

"It was the most exciting 'hope' I have ever sung," Shapira writes.

As is the nature of quite a few autobiographies, Shapira fails to avoid unnecessary and burdensome apologetics, especially in the chapters devoted to her public activity, which has always been the forerunner of the labor movement (and has even been offered political appointments to the Knesset list and ambassador to Moscow).

This culminates in pages dealing with the years in which she initiated and headed the establishment of the Rabin Center.

There is a feeling that instead of unfolding the full story of this venture, whose critics saw it as part of a politicization of Rabin's commemoration and even a political lifeline of the degenerate left and another source of budgets and jobs for "our people of peace," Shapira seeks to whitewash his problematic image, Things were not so bad.

Those familiar with the art of reading between the lines will find echoes of the real situation that prevailed in it.

"I never belonged to the fan entourage that accompanied Leah Rabin," the author releases a subtle hint to clue seekers.

Others will simply skip the pages dealing with the center, in a renewed search for sincerity.

This, by the way, will be found again towards the end of the book, when Shapira explains why she loves history, and her explanation can not help but arouse immediate sympathy: "Through the historical story I live the lives of others, glory I did not have, adventures that did not happen to me "Brides I have not had. My life has not been rich in adventure, heartbreaking dramas. It is history that allows me to sail to far more sublime worlds."

Anita Shapira / That's how it was, with an employee, 168 pages

Were we wrong?

Fixed!

If you found an error in the article, we'll be happy for you to share it with us