The tenor Mark Padmore performs Robert Schumann's 'Zwölf Gedichte von Justinus Kerner' in the first part of his recital at the Teatro de la Zarzuela.Rafa Martín

In just ten months of 1840, the year inevitably associated with his wedding to Clara Wieck on September 12, the day before she turned 21 (and came of age) and after both had gone through a painful personal ordeal and legal by Friedrich Wieck's adamant refusal to allow his prodigious daughter to marry his former student, an inexhaustible stream of songs poured from Robert Schumann's pen.

The opus numbers should not mislead us, since no matter how different they are, they frequently ultimately refer to creations born in what Robert Schumann himself baptized as his

Liederjahr

.

The torrent of creativity began on February 1, 1840 and abruptly ended almost a year later, on January 16, 1841. In those months no less than 139 songs were released, in addition to twelve duets and songs for various voices, whose visit to the printing press would expand in a constant trickle until 1858, already posthumously, in 23 different publications.

It seems clear, therefore, that this spectacular flowering cannot be due, as is often lightly asserted, to the happiness that the composer undoubtedly found to finally live with the woman he had longed for for years and whom he had known since she was a girl. little girl.

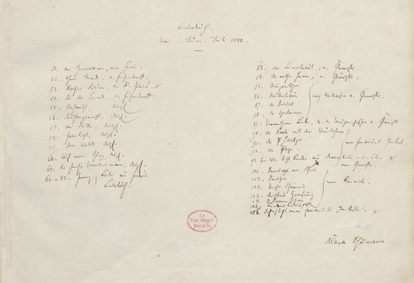

Handwritten list of songs contained in Robert Schumann's 'Liederbuch'.

The 'Dichterliebe' cycle originally consisted of the songs numbered 62 to 82. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

“Have you continued to compose songs?

Or are you perhaps like me, that all my life I have placed vocal compositions

below

instrumental music, and that I have never considered it a great art?

But don't tell anyone about this”, Schumann wrote to the composer and critic Hermann Hirschbach on June 30, 1839. The emphasis on the adverb is, of course, that of the musician himself and it is astonishing to read such a statement from the mouth of one who, very a few months later, it would give birth to masterpieces such as those contained in

Dichterliebe, Zwölf Gedichte von Justinus Kerner

(the cycle and collection of songs that Mark Padmore and Kristian Bezuidenhout have just performed in Madrid),

Frauenliebe und -leben

, the two

Liederkreise

opp.

24 and 39 or the

Myrthen

op.

25, conceived as a garland or bridal bouquet of songs for her fiancée.

After their wedding and the beginning of their coexistence in a house with a neoclassical facade on Leipzig's Inselstraße (now converted into a small museum), the Schumanns kept a joint marital diary, their

Ehetagebuch

, a must-read for all those who have lost their faith in the couple as a way of life.

On November 22, 1840, Clara, who was still experiencing the physical and emotional stress of the months prior to the wedding ("If there is something that can cloud my happiness at times, it is the thought of my father," she confessed a few days later) , wrote in the diary a characteristic entry of how he addressed his lover indistinctly in both the third and second person: “Robert has once again composed three wonderful songs.

The texts are by Justinus Kerner: '

Lust der Sturmnacht

', '

Stirb, Lieb' and Freud'!

' and '

Trost im Gesang

'.

He sets the texts to music beautifully and understands them with a depth unmatched by any other composer he knows.

Nobody has the feeling that he has.

Oh!

Robert, if you ever knew how happy you make me...indescribable!”

Kristian Bezuidenhout and Mark Padmore, whose hands almost single-handedly express the content of the poems.Rafa Martín

That same month “

Wanderung”

, “

Stille Liebe”

, “

Auf das Trinkglas eines verstorbenen Freundes”

and “

Frage” were also born.

, and Schumann himself referred in the newspaper to those last days of November as “a quiet week that I have spent composing and with many hugs and kisses.

My wife is love, kindness, and modesty personified.

She [...] she is also gradually regaining health and energy, and the piano is opened more often.

[...] I have concluded a small cycle of Kerner's poems;

Clara has brought happiness, and also sadness;

because she often has to pay for my songs with silence and invisibility.

That's the way it is in artist marriages, and if the two of you love each other, that's fine."

In December came “

Stille Tränen”

, “

Erstes Grün”

, “

Sängers Trost”

, “

Wer machte dich so krank?”

and “

Alte Laute”

, almost a reflection of his own married life.

Schumann even cites the seventh piece of her

Kreisleriana

of hers (which Clara frequently played at home during the first months of her marriage) in the accompaniment of the last two songs cited (and in identical measures, from the sixth to the tenth).

More information

Robert Schumann: all the songs of the nightingale

And when the composer himself already considered the cycle finished, “

Sehnsucht nach der Waldgegend”

still arrived , which Robert offered Clara as a Christmas present, and, on December 29, about to conclude that miraculous “year of songs”, “

Wanderlied”

would still see the light

, which hides another quote that reveals the deep links of this

Liederreihe

with his private life: when he set the verses “

Und Liebe, die folgt ihm,

/

Sie geht ihm zur Hand

” (“and the love, that follows him, / stays by his side"), Schumann cited the main motif of the sixth song of

Frauenliebe und -leben

, "

Süßer Freund

”, not coincidentally the one that refers to the protagonist's pregnancy: Clara herself was also pregnant (with her daughter Marie), as she herself had just confirmed to Robert.

Of the total of fourteen songs, with a view to publication, and as would happen three years later with four of the twenty destined to be part of

Dichterliebe

, Schumann finally discarded two of them (“

Trost im Gesang

” and “

Sängers Trost

”) , which would be published in other opus numbers.

Handwritten sheet music for the first song of Robert Schumann's 'Dichterliebe', 'Im wunderschönen Monat Mai'.Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

The twenty songs of

Dichterliebe

were born, however, in little more than a week at the end of May of that same year, with authentic explosions of creativity that allowed the birth of several songs on the same day.

Its publication was delayed, however, until the month of August 1844, with those four songs less than the twenty originally conceived to integrate what from the cover is clearly identified as a "song cycle", that is, in the wake of

An die ferne Geliebte

by Beethoven or

Die schöne Müllerin

by Schubert.

There is no story told here, nor is there a single protagonist, but Heine, with his

Buch der Lieder

, provided Schumann with all the poetic material he needed to string, like beads on a necklace, a series of songs that expressed precisely the themes that most interested and worried the composer.

He thus also became the natural continuator of the six songs by Schubert based on poems by Heine that would posthumously form part of the collection baptized by the publisher, Tobias Haslinger, as

Schwanengesang

.

The first great master of Lied had found a successor, just as decades later it would be Hugo Wolf who would take over from Schumann.

With these three names is written, in essence, the glorious history of the genre in the nineteenth century.

Mark Padmore has been the best Evangelist of the Bach Passions of his generation, which is to say that he has been one of the best lyrical tenors of the last decades.

He has sung a lot and very well, encompassing a repertoire that extends from the Renaissance (he even collaborated with The Tallis Scholars, for example, singing music by Josquin des Prez) to contemporary creation, so it should come as no surprise that, being Already in his sixties, his voice begins to show the inevitable wear.

In a few days, next Saturday, he will perform Winterreise

at Wigmore Hall.

by Schubert together with the pianist Paul Lewis, thus putting an end to an artistic residency throughout this season after which he has already announced that he will no longer offer "complete" recitals in the historic London hall.

Perhaps he has decided to initiate a progressive withdrawal.

If so, and even more so after what we heard at this Madrid recital, we're going to miss him a lot.

Three years ago, at the Aldeburgh Festival, Padmore gave several master classes on the performance of Britten's songs.

In Madrid he has sung Schumann, so admired and sometimes imitated by the author of

Peter Grimes,

but many of the observations he made then to his students are equally applicable now, because, like all good teachers, the English tenor leads by example.

In the first place, the diction: “The public should be able to write each and every one of the words that you are singing”, he then said to a soprano so that she would take extreme care in the pronunciation.

Closing his eyes, Padmore can understand each vowel, each consonant, but the way of pronouncing them (more open, more closed, more labial, more fricatives, more voiced, more deaf), and of singing them, varies substantially depending on the context, just as words sound one way or another depending both on their placement in the poem and who is the poetic person saying them.

In “

Stirb, Lieb' und Freud

”, one of the jewels of the op.

35 by Schumann and one of the best moments of Monday's recital at the Teatro de la Zarzuela, written in a strange double compásillo compasillo and with an archaic touch that suits both Padmore himself and his pianist wonderfully in this occasion, Kristian Bezuidenhout, we hear the girl referred to by the poet-narrator express herself twice in the first person.

With an almost white voice, without

vibrato

, Padmore was literally transfigured into it, opting even for the higher of the two options offered by Schumann when asking at the high altar to be accepted as a nun, despite the fact that throughout the afternoon the tenor English accused serious problems above the sharp Sun.

Going with the more serious alternative would have eliminated any risk, but it would also have reduced the credibility of the confession.

And not shying away from those or similar challenges, attacking high notes with the usual technique, but with a voice much more fallible than before (some long notes also suddenly lost color), was what, especially in the first part, gave gave rise to quite a few punctual tuning problems: in “

Stille Tränen

”, very demanding, that discomfort in the high register was especially perceptible, which did not prevent the version from being extraordinary, with that magnificent final

diminuendo

in “

sei sein Herz

”, an echo of the poetic atmosphere of

Dichterliebe

.

Hands that seem to implore in a characteristic gesture of the tenor Mark Padmore.Rafa Martín

Padmore was undeterred by the attempts of adversity and continued to sing as he always has, walking on the wire and relying on his extraordinary falsetto.

He could mark isolated notes, but what he did not fail in once was applying other teachings that he tried to transmit to his students at Aldeburgh: “You have to know how to convey how much you like this poem, you must have it perfectly internalized in your head, we need you to that poem is channeled through you”, he advised.

It is difficult to say and structure a poem better than Padmore does: when he faces the first line, the last line is already on the horizon, unlike those interpreters who chop up each sentence and are unable to give them a global meaning.

It was revealing, for example, his way of approaching “

Erstes Grün

”, under which Schumann writes simply “

Einfach

”, which in Padmore's version translated into the greatest simplicity and naturalness imaginable, grading stanza after stanza the growing emotional intensity of the poem.

In “

Stille Liebe

”, the indication is again meager, “

Innig

”, and he finds it hard to imagine the song conveyed with greater intimacy.

In curious homophonic songs, such as “

Auf das Trinkglas eines verstorbenen Freundes

” or “

Frage

”, the perfect understanding between singer and pianist could be verified more than ever.

The two are united not only by the assiduous cultivation of ancient music, but also by a conception of interpretation in which personal brilliance or any hint of excess are completely out of place.

When Padmore sings, it is convenient to look at his hands, because in them his interpretation seems to be born, or summed up.

Sometimes they touch, others separate, others seem to implore, others withdraw, others draw a hug, or write a farewell.

We have recently heard Christian Gerhaher and Matthias Goerne sing Schumann at the Teatro de la Zarzuela.

Padmore perhaps embodies a third way, without the hypergesticulation and vocal mannerisms of the second, but also without the preciousness in the construction of each phrase and the smooth intellectualism of the first.

The Brit brings a greater degree of spontaneity and achieves the miracle of seeming that he is singing in a small room for a small group of friends: it is an intimacy that is sometimes painful, as was especially evident in the block of songs by

Dichterliebe

that goes from “

Hör' ich das Liedchen klingen

” to “

Allnächtlich im Traume seh' ich dich

”, but which also exudes truthfulness and conviction.

Only a more accentuated drama was missed in “

Im Rhein, im heiligen Strome

” (with the dots insufficiently highlighted on the piano) and in “

Aus alten Märchen winkt es

”, which invites a somewhat more exultant tone.

Mark Padmore and Kristian Bezuidenhout appreciate the audience's applause at the end of the first part of their recital.Rafa Martín

It was surprising that Kristian Bezuidenhout played a modern piano, since he has recorded this same repertoire with Mark Padmore on an 1837 Erard: historical instruments are, in fact, his great speciality.

But what the South African did was play a Steinway

almost

as if it were an Erard in a constant exercise of restraint and delicacy.

He never exploited its full sonic potential, not even when Schumann's

fortissimi

and our modernized ears seemed to claim or miss him.

He was always content, sober, too austere in terms of expression at times when the music invites greater effusiveness, but everything was framed in a perfect exercise of coherence.

Bezuidenhout embroidered piano epilogues as substantial as those that close “

Stille Liebe

” or, of course, “

Die alten, bösen Lieder

”, the last song of

Dichterliebe

and of the recital, on the last verse of which Padmore waved his right hand slightly in the air as he sang the word “

Schmerz

” (pain).

The public knew how to understand a recital carried out from budgets that were significantly different from the usual ones and Padmore and Bezuidenhout appreciated their persistent applause by interpreting “

Dein Angesicht

” off the program, one of those songs originally intended to be part of

Dichterliebe

, but that would end up out of the cycle and would be published years later in op.

127. It linked very well with the previous one, because the face of the beloved that Heine describes is “sweet and angelic”, while “so pale and full of pain” (“

schmerzenreich

”), a pain that was also visible, for course, in the virtuous and polysemic hands of Mark Padmore, a singer —and an artist— unrepeatable.

XXVIII Lied Cycle

Robert Schumann:

Zwölf Gedichte von Justinus Kerner, op.

35

.

Dichterliebe, op.

48

.

Mark Padmore (tenor) and Kristian Bezuidenhout (piano).

Zarzuela Theatre, June 20.

50% off

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber