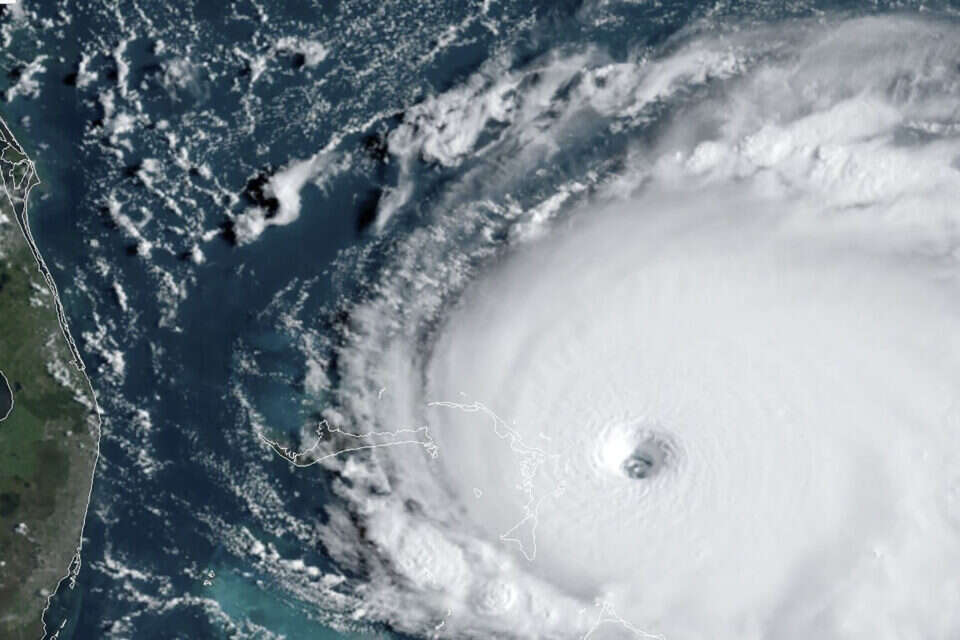

A future-contemporary dystopian world, in which the climate is the great fear of the people who want-not-want-to-know about the impending disaster, is at the center of Tamar Weiss Gabay's original and thought-provoking novel, "The Forerunner," her third book for adults.

From the very first paragraphs, a conflict that transcends human boundaries develops here, when the opening sentence of the novella - "She entered in a measured step into the main street of her town" - plays with the iconic cinematic frame of Sheriff (albeit here of a female gender), marching on the main street of the remote town. In that order.

But the war described here is different from the Western wars.

While the sheriff is fighting flesh-and-blood lawbreakers, the forecaster is waging a much tougher war: its enemy is nature, and no less - the fear of it.

The remote, nameless town, nestled in a mysterious desert landscape, is subject to devastating, unpredictable floods, and residents are turning a blind eye to the weather forecast.

Its function is not to tame nature or subdue it - it is beyond its powers - but to instill in the inhabitants a false sense that it has the ability to anticipate the floods and allow them to prepare for them.

In other words, its job is to deceive those who have some right of way over the destructive powers of nature.

The residents hang false hopes on the skirt as if she were a savior, seeing her as "a cowboy who threw a lasso, captured the raging weather and put a bridle in his mouth."

But she is not a savior;

In fact it is closer to a false prophet.

Her predictions, when read well, do not serve as reassurance - they are cautious, frightened, weary reservations, which reveal a great deal of lack of control.

When she is accused of making a mistake in the prediction, she defends herself: after all, she explicitly wrote "chance of dripping" and not "dripping", she wrote "there may be haze" and not "haze".

According to her, she is accurate.

But the people are not ready to read things as they are, to accept the helplessness, the inability to predict nature and defend against its calamities, and its status as "sheriff" of the town is undermined.

"The Skeleton" is a three-part novella, which is also three generations.

After the first part, which deals with the midwife herself, a middle-generation climatic crisis, comes the second part, "The Teacher", which deals with her father, who is also a literature teacher in the town, and the third, centered on the so-called "girl". With her for the duration of her studies.

The three characters, like the town, have no name, and this particular absence, as well as the schematic structure of the novel, which connects each of the three to a distinct ideological position, invite each of the parts to read about three stages, or three different positions, in the human-nature crisis.

First there was the patriarchal generation, represented here by the teacher, the father / grandfather, who believes wholeheartedly in the greatness of the intelligent human spirit.

He despises low intelligences like those of dementia patients or newborn babies, who do nothing but eat and ejaculate, and do not rise in his opinion from the "sea cucumber" level.

Although he loves nature and knows it well, he sees in his eyes a clear boundary line between the person with consciousness and other inferior life forms.

It is not for nothing that he teaches his students, and his granddaughter among them, Hemingway's "The Old Man and the Sea", quotes from which are generously embedded throughout the novella, and especially repeats the sentence that appears on the back cover of the Hebrew translation: A giant who embodies the noble in nature. "

The grandfather, like the fisherman in "Old Man and the Sea," sees the relationship between man and nature as a battle between the strong, and believes in the human ability to know and control nature, albeit out of respect, but this anthropocentric view is questionable throughout the book and can be read as an ongoing appeal.

In a sense, the "skirt" begins after the "old man and the sea" end - with the loss of both sides: the fish dies, the fisherman fails.

Now that both man and nature are defeated, future generations (the "girl") must find a new way of formulating the attitude towards it.

If mastery of nature is doomed to failure, and it is impossible to predict it, what path remains open to the girl's contemporaries?

What will the long-awaited reconciliation involve?

In an attempt to answer these questions, the "forecaster" quarrels with the "old man and the sea" on both the conceptual and the formal level.

Both are defined as novelties, and both shake off the plot and descriptive breadth of the novel, but while Hemingway's pushes its limits with the power of the electrifying human and animal powers she describes, in Weiss Gabay's writing takes on a more modest and minor strategy.

It is not a writing that glorifies the heroism of the human condition or a glimpse into its abysses, but draws the obligatory conclusion from the need to break the hierarchy between man and nature and leaves its characters — their aspirations and failures — in more earthly, limited dimensions, at ground level.

While the literature teacher, the father of the forecaster, lectures his students on literary works "like a thing on a huge rock, a cliff against the sky" - these works are for him an astonishing sublimity - Weiss Gabay's writing, in principle, strives for writing with more crystalline materiality, Similar to the dry lands around the town.

The dialogue with "The Old Man and the Sea" might have cast a crippling giant shadow on the book, but it manages to breathe life into it thanks to the encapsulated question it raises towards it: If man needs to change his relationship with nature, what does that say about literature?

Should she also change her lofty aspirations, her form?

Although "The Skeleton" sometimes suffers from an excess of didacticism, and the triangular structure that parallels the three characters and three ideological and generational positions is too illustrative - Weiss Gabay's writing manages to maintain a sober sharpness while striving for a reconciling optimistic vision, and swallows a fascinating literary-ideological proposition: Man’s relationship with nature may also require a literary change, not only in the way we read our masterpieces but also in the writing forms of the works to come.

Tamar Weiss Gabay / The Forerunner - Novel in Three Parts, Locus, 91 pages

Were we wrong?

Fixed!

If you found an error in the article, we would love for you to share it with us