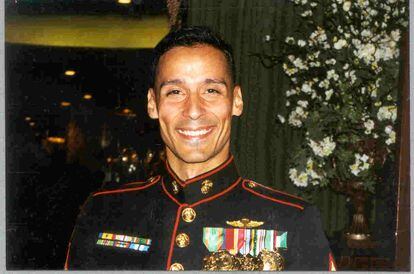

José Luis Pereda was a Marine in the United States Armed Forces for 13 years.

Between 1990 and 2003 he participated in three wars: the Gulf, Somalia and Iraq.

Insists a lot on the

switch

of the soldier: that internal switch that those enlisted in the army turn on to become a “lethal weapon” and that later, after their years of service, they must manage to turn off to reintegrate back into society.

Pereda considers himself a serious person with a character that can even become violent.

"For me, any friction or disagreement with someone can turn into a fucking battle," he says.

He has always attributed that attitude to the training he underwent and the aftermath left by so many years in the Corps.

In fact, he suffers from a "chronic" post-traumatic stress disorder, a product of the harshness that he experienced on the battlefield and that led him to need therapy.

Now, after two decades descending into the hells of war, the 55-year-old ex-Marine thinks those rages go back much further, from his childhood.

Specifically, from when he was nine years old and was an intern at the Claretians' Corazón de María school in Zamora.

Pereda narrates that Father Félix sexually and physically abused him there during the academic courses of 1976 and 1978.

Some memories that, he says, he has kept buried for almost five decades.

Until last December, after learning that EL PAÍS was carrying out an investigation into pederasty in the Spanish Church, he decided to send a letter to the newspaper.

Months later, in April, he was able to tell it out loud for the first time.

In the first conversation with this newspaper, he had a self-disclosure: “I have dealt with my post-traumatic stress disorder from the war, but the problems of my childhood have not been dealt with.

And that anger has remained alive, without control.

It hasn't healed properly."

And he defined himself: "I am a war veteran, a victim of post-traumatic stress disorder and a survivor of pederasty in the Church."

More information

The Spanish Church investigates a second report on pederasty with 278 new testimonies

Like many victims of abuse, Pereda suffered his torment in silence: "I thought that if I told someone they would tell me that I had asked for it."

He says that he didn't want to think about it because he believed that if he remembered it, he would conclude that it was his fault.

She buried those episodes and admits that for him it was as if the memories of that nine-year-old boy belonged to someone else.

But now he is aware that they are not, that they are his.

They were preserved intact, sharp and vivid, in a corner of his memory.

"It's like those years are frozen in time," he reflects.

When he talks about the abuse and his life in Zamora, he switches from English to Spanish.

It takes him only a few minutes to find the words in Spanish, but as soon as he picks up the rhythm he launches into telling everything.

Pereda was born in New York in 1967, but when he was seven years old his father, of Spanish origin, took the family to Zamora.

There he enrolled in the Corazón de María school run by the Claretians.

With his father sick and separated from him, Pereda and her two brothers ended up in 1976 residing in the center's boarding school, including summer vacations, when most of the children returned to their families.

That summer, Pereda recalls, the sexual abuse began.

“One day, my little brother and I got up early and went for a walk around the school.

When we returned to the dormitories, we ran into Father Félix”, she narrates.

They greeted him, but the priest “exploded”: “he started hitting me and told me to go to his office”, he continues.

His brother, he adds, managed to get away, but Father Félix continued to beat Pereda.

Once in the defendant's office, he describes him, he asked him to take off his pants and underwear: “I did not stop crying, I did what he asked me under the threat of more slaps.

So, he grabbed my penis and shook me while trying to hit me,” he says.

The attacks were repeated "at least half a dozen times", until Pereda left school in 1978. "On another occasion he abused me in a small office he had on the stairs of the bedroom, which he used to make announcements over the loudspeaker", recounts.

“That time he used one of the shovels that we used to play handball.

He didn't try to penetrate me with it, it would be impossible, but he did try to touch my private parts.

He was pushing her hard against my crotch or my anus, depending on which direction she wanted me to look,” she narrates.

If Pereda tried to resist the abuse, the defendant "would get furious" and hit him "so hard that he often lost his balance."

“He made me stand there naked, exposed, humiliated.

He would start hitting me and then grabbing me.

I was just a kid, and he was a brute,” he recalls.

Sequence of a school video where the accused Claretian appears while officiating a mass.

Pereda does not remember Father Félix's last name, but he does remember his face.

She recognized him from a school video from the 1970s that she found on the internet.

As this newspaper has verified, in a Facebook group of former students of the Claretian center, another former student also identified the accused in a publication as Father Félix, nicknamed

Cruyff

for his possible resemblance to the soccer player and deliveryman Johan Cruyff.

Father Félix was the prefect of discipline at the Claretian school, according to Pereda.

After receiving a call from this newspaper, a spokesman for the province of Santiago of the Claretian Missionaries has made himself available to the victim and has assured that the order is investigating this case, as well as the other 14 that EL PAÍS has sent him. till the date.

He has also confirmed that in Zamora, in the seventies, there were two Claretians named Félix.

However, he has not specified the last name of the religious Pereda accuses, although he has guaranteed that the congregation is collecting the necessary data to identify him.

The war: an exit to the memory of the abuses

It is a Friday morning at the end of April in Williamsburg, a Brooklyn neighborhood located on the slopes of the East River in New York, from where the Manhattan skyline is best admired.

A fierce wind blows.

One of those last bursts before New York spring finally gives way to summer.

Those that make it difficult to walk, talk, see.

Pereda, for his part, seems unshakeable: he is almost two meters tall and stands firm, serious.

It is the first time that he has spoken face to face with a person about his history of abuse.

During a walk through his neighborhood, he says that New York is a very aggressive, even violent city.

But it is his home.

He has visited 55 countries and lived in 16, but he always ends up coming back here.

After leaving the Claretians boarding school, Pereda continued his studies in public schools.

He studied Hispanic Philology at the University of Valladolid, and when he finished his degree he returned to the United States in 1989. Without really knowing what to do with his life, he followed in the footsteps of his older brother, who was then in the US Navy.

In his case, Pereda chose the Marines.

Upon entering, in 1990, he was selected for the special reconnaissance unit, considered an elite force within the Marines.

Simply put, the mission of a reconnaissance marine is to penetrate enemy lines and obtain secret information.

To do this, he went through many trainings and specializations, including tortures such as prolonged starvation and the practice known as the

wet submarine.

, which consists of immobilizing a person face up on a table, covering their face with a cloth and pouring water into their mouth and nose to generate the sensation of drowning.

“Now that I think about it, I think I was obsessed with learning these survival techniques because of the trauma I had from my childhood,” he confesses.

José Luis Pereda in 2003, when he left his post in the United States Marine Corps.

Pereda describes the army as "an illusion."

Within that mirage, he explains, "you are forced to forget everything the world of civilians has taught you and to repress that part of your life."

In his case, there was a rift between the person he was before he joined the military and the person he became upon enlisting.

“The military completely transformed me, gave me a new purpose,” he says.

On a grand scale, his new goal was to serve his country.

On a small scale, surviving, whether it was crossing the Colorado State River in military training or taking control of a cigarette factory during the 2001 invasion of Iraq. And in situations like these, he didn't have time to remember the past.

She was getting further and further away from him.

“For me, the Marines were a distraction.

I learned to compartmentalize my trauma,

"In addition, I experienced worse traumas during my military career," he adds.

Pereda assures that he cannot detail anything he did or saw during his time in the army until 20 years have passed since he left his post, that is, until September 2023. However, he admits that the horrors of the wars in those who participated persecute him to this day.

He left the Marines in 2003, and since then, every night he's moved back to the battlefield: "In my dreams I always end up back in my uniform, like I'm still there."

"My post-traumatic stress disorder is chronic, it is always present," he laments.

She has gone to therapy twice to deal with him.

The first time was just after leaving the army.

Remember that he only went to one session.

He was prescribed antidepressants and he never came back.

A decade passed before she tried again.

This time he stuck and went for a year, both in group therapy for veterans and in individual sessions.

He constantly fears how he will react to a conflictive or tense situation.

“Someone like me, who has gone through the kind of military training that I have gone through, can be a danger.

What we are capable of doing should not come to the surface.

It's deadly and you could end up hurting someone,” he admits.

In his day to day life, he tries to avoid places where he might come across people who provoke him,

—Do you think that by facing the aftermath of the army, you have avoided processing and dealing with the trauma of the abuse you suffered during your childhood?

—The thing about war-related post-traumatic stress disorder is that it buries any other type of trauma you had before.

It is now that I have been able to reflect on the abuses.

Pereda is convinced that the "demons" he has carried all these years have cost him five marriages.

“In my relationships I was always arrogant, selfish.

My problems come from this trauma that I have, and not only from the army, no.

I have to go back to my childhood to understand it.”

If you know of any case of sexual abuse that has not seen the light of day, write to us with your complaint at

abuses@elpais.es

.

If it is a case in Latin America, write to us at

abusesamerica@elpais.es

.

50% off

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/2LRPBTQQ4E4LXICPWKPWK2HCIQ.jpg)