What is a polymath?

The dictionary defines the term, derived from the Greek, as a person "with great knowledge in various scientific or humanistic subjects."

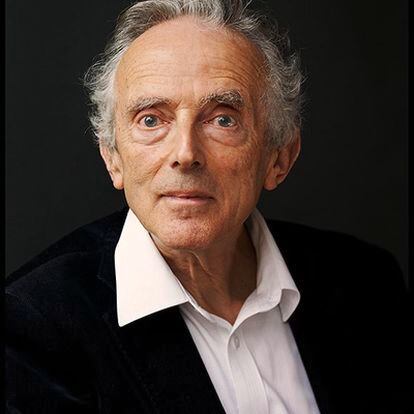

The great cultural historian Peter Burke (Stanmore, United Kingdom, 84 years old) offers in his new essay,

The Polymath

(Alliance), a much more detailed description to understand who were the "monsters of scholarship" who managed to make simultaneous contributions in different fields, from Leonardo da Vinci to Susan Sontag.

"To be a polymath, you have to have a greater sense of curiosity than the rest and a good sense of analogy, enough open-mindedness to believe that the solutions you find in one discipline will work for another," he points out in his office in Cambridge, where he is now professor emeritus of cultural history after having taught at the prestigious Emmanuel College for 40 years.

The list that Burke provides in his book reaches up to 500 names, from Comenius to Oliver Sacks, including Albert the Great, John Dee, Newton, Jefferson, Humboldt, Pascal, Montesquieu, Voltaire, Marx or George Eliot.

The author considers that history has not always treated them well.

In the era of academic specialization, there has been a certain reluctance to admit that there were personalities who broke the rules of compartmentalized knowledge that reigns in the present and managed to widen the frontiers of knowledge.

“Personalities with multiple interests, from Leibniz to Borges, are remembered for only one of their different facets.

It is easier to remember the past in a way that fits the present”, says Burke, who does not consider that he fits the definition of a polymath, despite his proven knowledge in history, philosophy,

sociology, anthropology, economics and politics.

"But I don't know anything about science, I'm terribly ignorant in that field," she excuses herself.

“If I am a polymath, it is in a very

light

”.

British historian Peter Burke.British Academy

Even so, his essay can be read in an autobiographical key, as an apology for interdisciplinarity, which would have been, during a long and brilliant academic career of six decades, his way of apprehending intellectual life.

A historian in his twenties, Burke left Oxford, where he had been educated at the legendary St. John's College, to work as a professor in Sussex, where he opened one of the

new universities .

established after the Second World War, with the freedom to offer a new type of multidisciplinary learning.

In 2003, that university decided to adopt a more traditional curriculum, separated into majors.

“They did it because they said that good students didn't want to study there.

Over time, a pragmatic generation appeared who worried about not finding a job”, explains the historian.

"I understand it in times of crisis and, at the same time, I think they are wrong: companies are still looking for individuals with great intellectual flexibility."

Perhaps we are losing the ability to read the old way, in a linear way, from beginning to end”

Burke himself eventually left Sussex in the late 1970s for Cambridge, with a much more conservative curriculum, but taught at nine different colleges, until he retired in 2004, when the internet had already disrupted our access to information. information.

That process has since accelerated, which worries him.

"Maybe we're losing the ability to read the old-fashioned way, in a linear way, from beginning to end," says Burke.

“I know of people who say that while they love technology, they are worried about the effects it is having on their brains.

If that becomes general, we will have a problem.”

When he leaves his office, carpeted in a light blue hue and

British

to the core, he always wastes a few minutes chatting with students who play

crocket

in a cloister straight out of an Oscar-winning historical drama.

We ask him if he detects in them a lower intellectual capacity than his.

“I keep having very interesting conversations with them and I don't think anything bad will happen to them.

But I do think that there are losses linked to the gains that have come with technology…”.

The Internet could be the perfect invention for everyone to become a polymath.

Actually, his book suggests that it can cause an overdose of information that, paradoxically, makes us more ignorant, as happened after the invention of the printing press.

“There is a temptation to be more and more intellectually lazy, to go to Google or Siri all the time.

It is very practical to know the distance between London and Edinburgh in a couple of seconds.

Although, if everyone is in that position, who will start by measuring the kilometers?

Who will feel the incentive to become an academic or a polymath?” she replies.

He hopes his book isn't "an elegy for the polymath," though he worries that will turn out to be the case.

Does not Burke make the same mistake as so many others before him, who in past centuries ruled, as he recounts in his book, that the time of great scholarship would end with their deaths?

"Actually, I'm open to the idea of one among us, but I can't think of one born after 1960."

In his book, the

youngest

of the 500 polymaths cited, all of them dead, is the paleontologist, biologist, geologist and historian Stephen J. Gould, born in 1941. Although, at the last minute, Burke decided to add an appendix with some alive.

"My wife warned me that if she didn't do it, she was going to make me a lot of enemies," smiles the author.

contemporary interdisciplinarity

Among them, the presence of many women emerging from gender studies is surprising, such as Judith Butler, Gayatri Spivak or Julia Mitchell, who lives just around the corner;

all of them examples of contemporary interdisciplinarity.

They are not the first scholars to appear in the book, although they are not many, having been excluded from the academic world (or marginalized, at best): the author cites Hildegard von Bingen, Margaret Cavendish, Margaret of Sweden , Joan of the Cross or Madame de Staël.

The essay also points to the tragic failings of these intellectual heroes.

In the first place, the so-called Leonardo syndrome, or the inability to complete an investigation, having the mind scattered in different disciplines.

And, in the second, the arrogance, which Burke detects in George Steiner or in Foucault, whom his friend Carlo Ginsburg called a "charlatan" in his day, just as Isaiah Berlin did with Derrida.

"All in all, I prefer the arrogance of knowledge to that of ignorance," jokes Burke.

He will dedicate his next essay to this topic, a cultural history of intellectual innocence, which he will have ready for 2023. “It is an issue that has always been part of who we are and that continues to have a great future ahead of it,” concludes Burke with media smile.

50% off

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber