She was not just one of Picasso's countless models, nor was she just the companion of surrealists like Man Ray.

It's been a couple of decades now that the history of art has removed Lee Miller from the reductive box occupied by the muses, that term from another century, to extol her work as a fashion photographer at the service of the best women's magazines and also as a war reporter in Europe during World War II, although her work remains less well known and applauded than that of many of the male artists she frequented.

The Arles Encounters, the main festival dedicated to the image on the European continent, now consecrate an exhibition to the American artist conceived as a definitive gesture to reaffirm her contribution to the visual culture of the 20th century.

"My goal was to show only his work, leaving out the glamour, the biographical and sensational details, his relationship with Man Ray and his mental health problems when he returned from the war front," says curator Gaëlle Morel, behind an exhibition that It can be visited in the French city until September 25.

The exhibition focuses on the period between 1932, when she interrupted her activity as a model and created her studio in New York, and 1945, the year after which she gradually abandoned photography, traumatized by her experience in the Dachau concentration camps and Buchenwald, of which Miller was one of the first external testimonies.

"I beg you to believe it to be true," read her first telegram from those places.

The images of her served to prove that the furnaces of destruction existed.

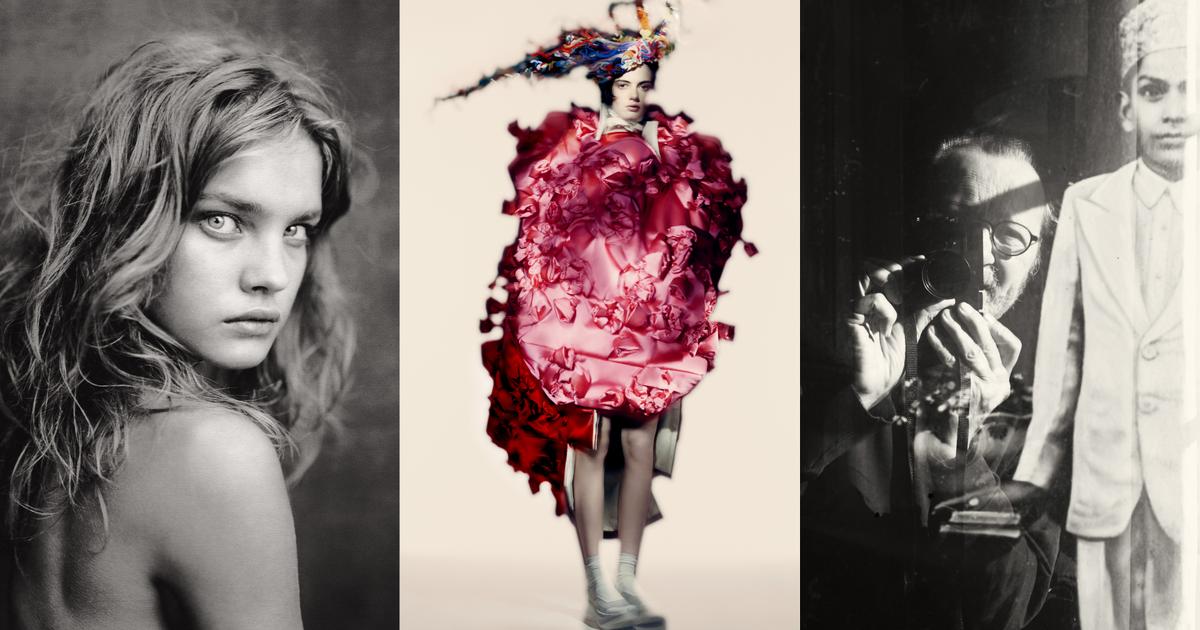

The model Patricia Francome Painter, in a photo by Lee Miller made in the 'Vogue' studio, in London in 1944.

The sample, with almost 200 images and documents, reflects their two souls in two symmetrical halves.

There are the exquisite fashion series with which she became known during the thirties and the campaigns at the service of houses like Chanel or Schiaparelli.

And then, in a radical twist, the images of her full of trains to hell, corpses in a row and emaciated prisoners.

The mix is somewhat schizophrenic.

What went through her mind in the winter of 1941 to drop everything and, with two

rolleiflex

hanging from her neck, ask for a war reporter's accreditation for

Vogue ?

?

“It was not such a strange case.

In that context, photographers were artisans capable of moving from one practice to another.

In addition, he had the will to participate, to leave a testimony of the war by doing what he knew how to do”, responds Morel, who discards the clue of a supposed frustration caused by fashion to understand that sudden change.

In reality, he continued to work normally in both areas.

In various photos from 1944, she is seen photographing the beaches of Normandy, dedicating a series to the latest collection of woolen garments in her London studio, and later visiting Picasso in his Paris studio.

In a letter collected in the sample, scribbled by the legendary editor-in-chief of

Vogue

, Edna Woolman Chase, during a visit to the hairdresser, congratulates her on her work on the front, but asks for more photos of children doing cute things on camera.

The allied army understood the importance of allowing photographers to follow their activities: it allowed them to raise public awareness and carve out a flattering image.

That Miller worked for

Vogue

was another point in her favor, since with her they were going to reach the upper-middle class female audience that read the magazine.

However, there was no propaganda in the work of the photographer, with a very free and even insolent personality.

It is demonstrated, above all, by the self-portrait that she made in Hitler's bathroom in his abandoned home in Munich, the same day that the

führer

committed suicide in his Berlin bunker.

“For years he had his address written in his pocket.

I took some photos of the place and slept in his bed.

I even cleaned off the Dachau dirt in his bathtub,” she once said.

Pablo Picasso and Lee Miller, in the former's studio in Paris, in 1944. Javier Larrea (AGEFOTOSTOCK)

One of the most startling series exhibited in Arles is carried out by women accused of collaborating with the Nazis (or, worse still, of having had relations with them).

After the Liberation, they were shaved, swastikas were drawn on their heads and then paraded through the French streets.

Miller watches them with a mixture of derision and empathy.

After the war, Miller retired to a farm in Sussex with her husband, the painter Roland Penrose, and she devoted herself to cooking, until graduating from the prestigious Le Cordon Bleu school in Paris.

She died in 1977 in relative oblivion, having abandoned photography and leaving an archive of 60,000 negatives.

When her son discovered them, she proposed them to the MoMA in New York.

She replied that they were not interested: her mother was nothing more than "a footnote in the life of Man Ray."

The Arles Meetings now rehabilitate Miller once and for all, in an edition that celebrates the work of women photographers of the 20th century with exhibitions dedicated to the prestigious Viennese Verbund collection, which includes the work of dozens of feminist photographers from the years seventies, from Cindy Sherman to Francesca Woodman, or the work of Babette Mangolte, official portraitist of contemporary dance companies in New York in the same decade.

“It is one of the axes that I want to develop.

It's about looking at the past to better see the present and the future”, says the director of the festival, Christoph Wiesner, who opened this edition at the beginning of July calling for “rebellion against the cult of male genius”.

in an edition that celebrates the work of women photographers of the 20th century with exhibitions dedicated to the prestigious Viennese Verbund collection, which includes the work of dozens of feminist photographers of the seventies, from Cindy Sherman to Francesca Woodman, or the work of Babette Mangolte, official portrait artist for contemporary dance companies in New York in the same decade.

“It is one of the axes that I want to develop.

It's about looking at the past to better see the present and the future”, says the director of the festival, Christoph Wiesner, who opened this edition at the beginning of July calling for “rebellion against the cult of male genius”.

in an edition that celebrates the work of women photographers of the 20th century with exhibitions dedicated to the prestigious Viennese Verbund collection, which includes the work of dozens of feminist photographers of the seventies, from Cindy Sherman to Francesca Woodman, or the work of Babette Mangolte, official portrait artist for contemporary dance companies in New York in the same decade.

“It is one of the axes that I want to develop.

It's about looking at the past to better see the present and the future”, says the director of the festival, Christoph Wiesner, who opened this edition at the beginning of July calling for “rebellion against the cult of male genius”.

or to the work of Babette Mangolte, official portrait painter of contemporary dance companies in New York in the same decade.

“It is one of the axes that I want to develop.

It's about looking at the past to better see the present and the future”, says the director of the festival, Christoph Wiesner, who opened this edition at the beginning of July calling for “rebellion against the cult of male genius”.

or to the work of Babette Mangolte, official portrait painter of contemporary dance companies in New York in the same decade.

“It is one of the axes that I want to develop.

It's about looking at the past to better see the present and the future”, says the director of the festival, Christoph Wiesner, who opened this edition at the beginning of July calling for “rebellion against the cult of male genius”.

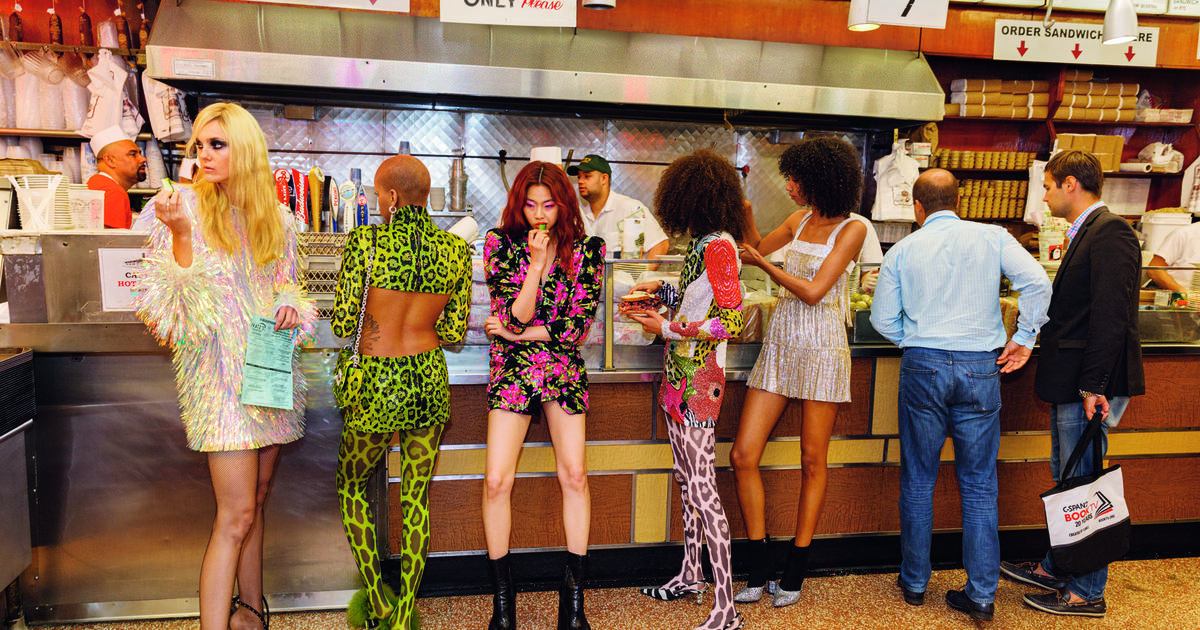

Eight decades after Miller, another fashion photographer like Annie Leibovitz has returned to travel to the war front to photograph the Ukrainian president and first lady, Volodymyr and Olena Zelensky, in Kiev for the cover of the next

Vogue

.

The result has sparked controversy on the networks, which have accused the photographer of frivolity.

The comparison with Miller's work, much more raw and solemn, does not necessarily work in her favor.

“Leibovitz places himself in glamour, while Miller believes in photography as a document, as an urgent testimony of a tragic and violent reality”, analyzes Morel.

The difference between her works says a lot about the change in status of fashion photographers, who today have the rank of stars.

“Miller was known, but Leibovitz's notoriety is light years away.

Consequently, in her work the protagonist is usually her and not the chosen subject.

In Miller's case she was always the other way around."

50% off

Subscribe to continue reading

read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/3VLEJSDWHVBTXIQ3PJMH7AC22Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/VQFWN5BD4VECJMCZ5VOL675H2Q.jpg)