It was the Bilbao of the 1990s and they made a mess of it.

Duels with motorcycles, fights in bars and squares, hashish and

speed

retailing , theft of construction material, small family extortions, some stab wounds in secondary areas of the body.

Stealing a toaster from the family home to sell it to a pawnbroker.

Fresh money to survive on the streets and live a fantasy image of oneself.

In the novel

Un tal Cangrejo

(Sexto Piso), the writer Guillermo Aguirre freely recreates his experiences as a teenage thug in the post-industrial Nervión, a member of a group of “wild children”.

And he reflects on what leads certain young people (himself) to pursue the ideal of the

badass.

Because the gangs, the juvenile delinquency, the macarrismo interest.

And the interest does not stop.

More information

The quinquis and macarras: on the other side of the myth

His novel, published in May, is the latest point in a line with ancient origins.

Rebel and violent youth gangs have been reproduced throughout history, as well as the interest in the phenomenon in cultural representations.

From the Apache gangs in Paris at the beginning of the 20th century to the aforementioned streets of Bilbao, going through films such as

West Side Story

,

Grease, Quadrophenia, The Warriors, A Clockwork Orange

, the quinqui cinema of José Antonio de la Loma or Eloy de the Church, or very current series like

Peaky Blinders

.

Each era has its gangs, with their characteristics and their own idiosyncrasies.

Why are gregarious and feral young people so attractive?

Why are those same young people interested in the dark and street side?

Still from the film 'West Side Story', in the new version directed by Steven Spielberg.©20th Century Studios/Courtesy Everett Collection / Cordon Press

“In adolescence, some people confuse respect and leadership with being feared, and to get there the fastest way is violence,” says Aguirre.

It is about reaching values of the adult world in another way, and it is achieved, but in a deformed way”.

The gang members think they are making a revolution, resisting the system.

"But in reality what they want is to enter that adult system before time," adds the author.

The street experiences allow those interested to fulfill the rites of passage towards adulthood with greater alacrity, while generating an interesting biography, something to tell and brag about, an identity.

The youth gang members, wanting to be antiheroes, cursed, carry out a curious investment operation: they turn the stigma into an emblem, showing off what society considers negative.

From the alley to the 'mainstream'

But, curiously, many triumphant aesthetics and attitudes among the youth, and not only the youth, come precisely from the badass, which frequently arrives at the textile franchises of the main avenues.

The tattoo, typical of the underworld and subcultures, today permeates the entire body, both literally and socially (even that of the police, the traditional nemesis of the gang member).

The

trap

music and reggaeton scene is an example of a slum, gang, and criminal aesthetic and ethic that, sprouting from both urban and global peripheries, has become a

mainstream

trend throughout the planet.

Don't Yung Beef, La Zowi, C. Tangana and even Rosalía want to be badasses?

These underworlds produce fascination in the general public, who enjoy it not from the alleys or the police stations, but from the sofa.

"We live in a very sterilized society, far from real passions, that is why we are interested in that dark side that most never get to experience in the first person," explains Iñaki Domínguez, an essayist who has published several books on the phenomenon, the last of them

Iberian Macarras

(Akal), based on intense fieldwork tracking down the pimps who formed gangs in Madrid and other cities in Spain during the last decades of the 20th century.

Los Ojos Negros, La Panda del Moco, los Miami, and even those groups of neo-Nazi

skinheads

that proliferated in the nineties persecuting beggars and immigrants or confronting leftist groups (which they called "dirty").

Clubs, territories, narco-flats.

“All these bands are part of an urban folklore that now has its public”, says the writer.

In Spain, many of these social manifestations arose in the context of the rural exodus of the second half of the 20th century, when people from the countryside moved to the peripheral belts of industrial cities in search of a better life.

They are the sons who go to the big city at the end of

The Holy Innocents

by Miguel Delibes (the novel) and Mario Camus (the film), leaving behind almost feudal labor relations, of gentlemen and day laborers.

A backward Spain.

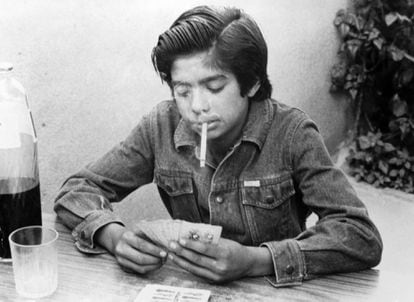

The actor Raúl García Losada, in the film 'Yo, el Vaquilla', by José Antonio de la Loma, exponent of the 1980s quinqui cinema in Spain. Album (IMPALA FILMS / Album)

Upon arriving in the cities, among the shanty towns that later became working-class neighborhoods, among the vacant lots and precariousness, some of the children of those workers went over to the criminal side, as the quinqui cinema portrayed: robberies of pharmacies, pulls to ladies,

bridges

in stolen cars, the heroin

rush

that ended up devastating them.

The weakest link in the working class that neither the unions nor the powerful neighborhood associations managed to protect, which was only dealt with by some worker priests and mothers' associations... but which attracted the morbid interest of the public (see the book

Chronicles quinquis

by Javier Valenzuela, published by Libros del KO, which includes texts published in this newspaper in those years).

The recent volume

The Forgotten.

Urban marginality and the quinqui phenomenon in Spain

(Marcial Pons), by Iñigo López Simón, also deals with the subject.

El Vaquilla, el Pirri, el Jaro, became media figures during the years of the Transition, the protagonists of the films used to be authentic quinquis, not professional actors.

"If then the bands had that homogeneous social origin, now they are multicultural, even in what we call 'Latin bands', people of different origins are mixed: Latinos, yes, but also Spanish, Romanian, etc.," adds Domínguez.

Today, there are those who have linked the aforementioned trap scene as the contemporary version of the quinqui, for example the director Juan Vicente Córdoba in his film

Quinqui stars

, in which the rapper

neoquinqui collaborates

El Coleta, from the Madrid neighborhood of Moratalaz, another great contemporary supporter of the imaginary of the old and delinquent neighborhood: the trap vindicates the tracksuit, the bad sex, the peripheral parks, the drug dealer (hence the name: the

American

trap houses come where

merchandise

is passed and consumed

).

The neoquinqui rapper El Coleta, in a promotional image of the film 'Quinqui stars', by Juan Vicente Córdoba.

The deep roots of youth gangs

From the cultural sector, almost no historical stretch has been left uncovered.

If the cited authors are dedicated to the most recent times, the publishing house La Felguera has also delved into past times, reaching the Parisian Apache bands.

"They were criminal groups in the Belle Époque that tattooed their entire bodies," says Servando Rocha, head of the publishing house, "they had a certain influence in Spain when they began to go into exile in the big Spanish cities, persecuted by French justice."

The four volumes of the series

Fuera de la ley

(La Felguera) are dedicated to anarchists, bandits,

protoquinquis

, hooligans or robbers, in addition to Rocha's novel

All the Hate I Had Inside

(La Felguera), which is introduced in these underworlds pulling the strings of the pimp and boxer Dum Dum Pacheco (also a regular source for Domínguez), who was a member of the Los Ojos Negros gang, with influence in the Madrid district of Usera already in the 1960s. During the Franco regime there were gangs, although they avoided the uniform so as not to be identified.

Other publications of La Felguera are dedicated to authors as notorious as Pío Baroja (the collection of articles

Las callees siniestras

), who had the pleasure of joining the marginality of the time, with the Parisian apachería, with the tavern environment, with the marginalized

troglodytes

from Madrid who lived in caves along Principe Pío, or strolling through miserable suburbs such as La Injurias or Las Cambroneras, on the banks of the Manzanares, today peaceful residential areas with other names.

“The history of the underworld, of the so-called dangerous classes, has not been told with dignity,” says Rocha, “but it is important to tell it to know what we are and what we were.

It's a story we can't give up."

Between what we call reality and what we call culture, a feedback occurs.

A classic example is the middling mobsters from the series

The Sopranos

, so everyday, that they were inspired by the contemporary mythology of

The Godfather

trilogy : a fiction not only inspires real beings, but also the characters of another fiction .

The characters of Robert de Niro or Al Pacino were his references.

Something similar occurs with flesh and blood youth gangs.

“

West Side Story

or

Grease

, which seem so innocent to us now, were very inspiring for the gang members of the time,” says Rocha.

In fact, in Spain there was a version of

West Side Story

called

Los Tarantos

(Francesc Rovira i Beleta, 1963) that replied in a gypsy version to those New York bands that, in turn, were a transcript of Shakespeare's

Romeo and Juliet

.

Another chain of chained fictions.

"The fact that fights between gangs dancing and singing were reproduced was seen in the media as a legitimization of violence," recalls the writer and editor.

The quinqui movies reflected a neighborhood reality, "but they also inspired other quinquis, like El Jaro, who liked

Perros calle

," says Domínguez.

The singer-songwriter Joaquín Sabina, in turn, dedicated the song

What too much!

to Jaro, where he described him as “Horny with tight pants / tattooed and suburban gang member / son of defeat and alcohol”.

In the movie

Buddies

(Eloy de la Iglesia, 1982), starring Antonio and Rosario Flores, in addition to José Luis Manzano, the great icon of quinqui cinema, this feedback is staged once again: the protagonists of the fiction speak in an arcade about the quinqui cinema movies themselves: “Well, for me, all the movies that have been made of pimps and such are a ful of Istanbul”, says one of the characters.

The way in which street gangs are portrayed in culture and the media has been criticized, especially when it is done in a stigmatizing manner.

In his essay

Youth Gangs

.

Culture and street conflict

, Mauro Cerbino describes how the media have traditionally portrayed these phenomena in a sensationalist way, choosing to report on the most lurid issues, generating stereotypes, and then taking advantage of that morbid image to gain an audience.

"Youth violence represents a social myth when it is conceived as something factual, gratuitous and natural, and not as associated with general problematic conditions," writes Cerbino.

Where youth and precariousness mix

Youth gangs arise from the union of at least two circumstances: the impetus of youth and the inability of the system to guarantee vital stability in certain areas.

"These groups arise from social vacuums, where the State has failed and violence and gangs are the only way to prosper and protect themselves," says Domínguez, "but that violence is also a symptom of that dislocation."

Where the system fails, it is natural for people to seek other forms of protection, new hierarchies, other ways of living and behaving.

Other tribes aside.

The appearance of street gangs could be used as a "thermometer" to measure the magnitude of exclusion, inequality, the contrast between those who fit and those who do not fit in the system, as Mexican anthropologist Rossana Reguillo has pointed out.

Gangsta rap band NWA: from left, Ice Cube, DJ Yella, Dr. Dre, Mc Ren, and foreground Eazy E, in March 1989.

Many gang movements arise in the United States, a country with a somewhat diffuse state, weak public services, and notable inequality.

Even some of what we call Latin gangs, like the Salvadoran gang Salvatrucha, which started in California, or the Latin Kings, born in Chicago.

Also the gangs around the genre of

gangsta rap

, gangster rap, which advocates violence and crime as a way of creating a strange community on the margins of society.

See the songs of

gangsta

groups like NWA or video games like

Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas

, which, probably, through the cultural hegemony of the United States, inspire new generations of gang members in an endless cycle that feeds on the economic and cultural situation, especially in times when the social gap and precariousness are increasing .

In cultural products about gangs, moreover, something profound is revealed.

“Adolescents live in a world of fiction, they imagine themselves in a fanciful way that does not usually materialize, they build a ghost identity, that is why, sometimes, they tend to enter into these imaginaries”, explains Guillermo Aguirre.

Those who are not in that vital moment or that social context, those who watch Netflix, find other things.

“We discover that violent part that we silence, we look at something that we do not do in our life together but that is also part of us”, concludes the writer, “what we see, we could do”.

50% off

Subscribe to continue reading

read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber