Sorolla had his dark side.

This resounding statement is literal, that is, it is about color, there is no metaphor in it.

Nor is there any when affirming that Sorolla painted

The Knight with the Hand on his Chest.

With his ruff and his tight black silk doublet, as dictated by the fashion of the sixteenth century.

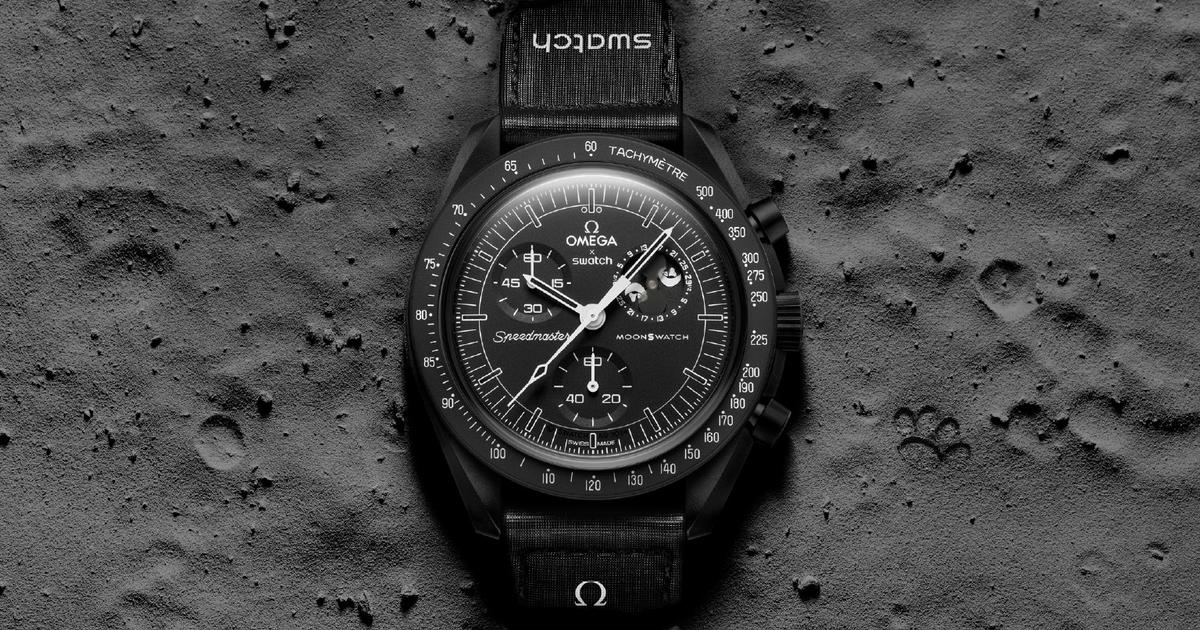

Two statements that expose some of the lines that the exhibition deals with that can be seen until November 27 in the Madrid house of the painter,

Sorolla in black

.

The curator, Carlos Reyero, confirms this: “If it were Sorolla in red, no one would doubt that it is a show about color.

Black is still a tone;

which, moreover, is rediscovered at the end of the 19th century.

One of the reasons why it regains currency at that time is because of the rereading that is being carried out of the Spanish masters who had used intense blacks, especially El Greco”.

These are times of unlearning.

In this case, to unlearn or to learn more.

Joaquín Sorolla (Valencia, 1863-Cercedilla, Madrid, 1923), often described as the painter of light, a master in the use of whites, also had his shadows.

He was the creator of beach scenes that are part of the collective summer imagination, a portraitist of water, of the reflection of the sun on it, of sand, of children, of his games and also of his work, including the invisible, but perceptible, breeze… But not only that.

He never banished black or dark tones from his palette, and Reyero wanted to stimulate the viewer, "take him out of his comfort zone and show another catalog, another thesis, not contrary to what is known, only complementary".

The visitor to the museum -located in the painter's house- crosses the garden, enters the spaces inhabited by the artist, his family and his illustrious friends, and goes up to the second floor, where the private spaces that are now dedicated to to temporary exhibitions.

For this exhibition, the walls have been painted gray, which encourages monochromy, the uniformity that Sorolla wants to show

off in black

.

The viewer enters into a sense of gray, but it is not gloomy or overwhelming, or at least not in all of his space.

'Sevillan Nazarenes' (1914), drawing made by Sorolla in Seville during Holy Week.

In a harmonic first room, full of portraits, the main tones prevail.

They, black or gray;

them, too.

They because in the 19th century they become uniform, the colorful colors of previous times disappear.

They, for elegance.

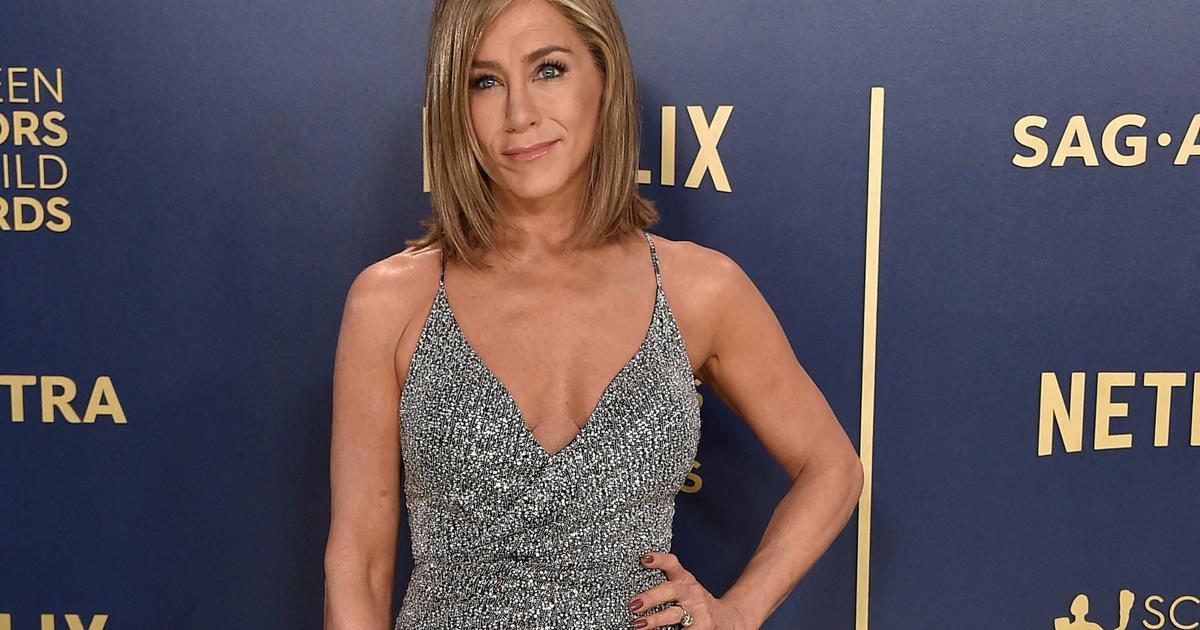

Sorolla liked women dressed in black, especially his wife, Clotilde García del Castillo.

There are dozens of cards that prove it.

“Tell me if you want a black silk dress, one of those that are so beautiful now”, he asks her from Paris on October 2, 1913. The next day he writes: “I have ordered your black silk suit: it will be precious (… ) I imagine the beautiful portrait I am going to do».

Among the characters in the room are his children (María, Elena and Joaquín), who are never absent;

his elegant wife dressed in gray;

the Nobel Prize for Literature, José Echegaray;

Queen Maria Cristina;

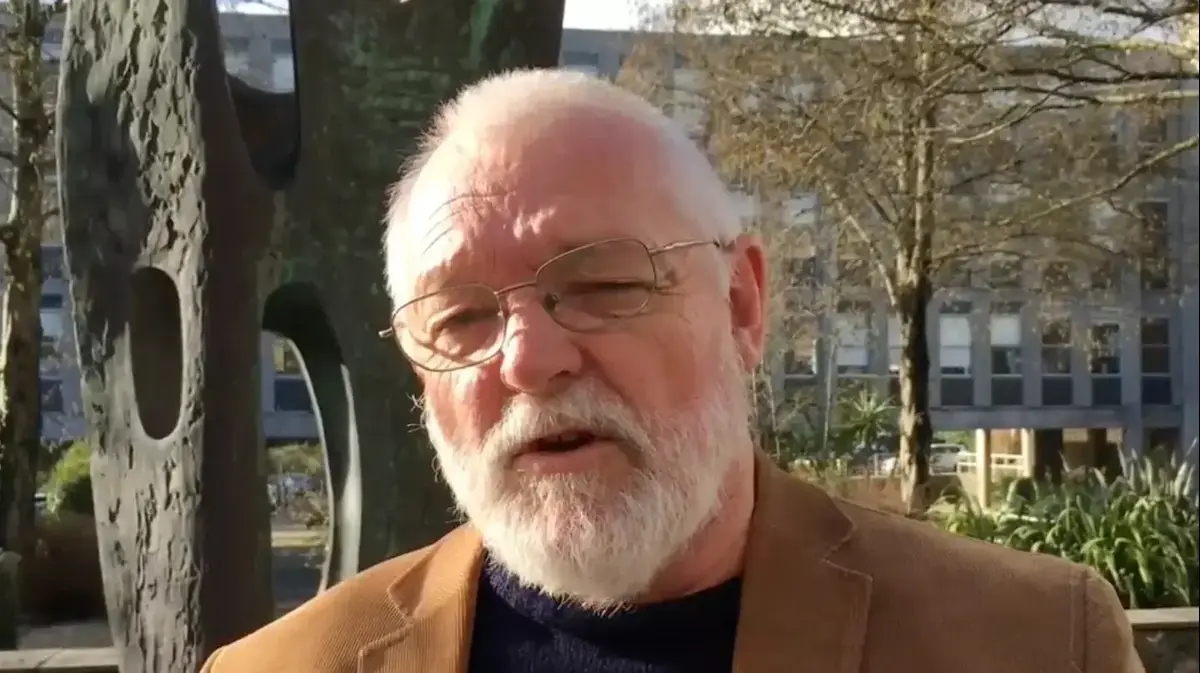

and friends like Manuel Ducassi or Manuel Bartolomé Cossío.

His brushstrokes are impregnated with the personality of each portrayed.

Thus, in the latter he creates the volumes through the different intensities of the blacks, a technique worthy of El Greco.

Not in vain, Cossío is the author of the first great study of the Cretan, hence after the character he paints a reproduction of

The gentleman with his hand on his chest

and generate a dialogue between his face and that of the intellectual.

"He could have painted the original painting, but he preferred a reproduction," stresses Reyero.

This influences the idea that the history of art was studied through reproductions (engravings or photographs) and these, until not long ago, were in black and white.

Thus, in a display case in the center of the room, he places photographs of Sorolla's works, as well as of family members or other paintings and leaves the question open: if art scholars would be influenced in the way of perceiving and explaining colors by his way of getting to know them, which was not always with the original work in front of him.

The next space is dedicated to that more negative symbolism of black.

Although the curator clarifies that the colors do not mean anything in themselves, each culture gives them certain values.

But as a painter of his time, Sorolla associates black with evil, death, and that can be seen in this room, where some of his crudest works are exhibited.

Canvases that capture the social problems of their time.

He represents what he sees, what his retina captures.

Valuations are separate.

In

White Slaves

(1894), he dresses in black whom he traffics in the lives of young girls.

In the studio for

Another Margarita!

(1892), the girl flanked by two civil guards is a tangle of dark brushstrokes, but it is not difficult to unravel the state of the downcast young woman, accused of having an abortion.

She reflects a burning social and moral conflict at that time, in which the woman is to blame.

It is probable that the artist witnessed a similar scene on a train from Valencia to Madrid.

As he also contemplated the Sevillian Holy Week of 1914, where he took many notes.

The Nazarenes caught his attention, at the top of one of these drawings he wrote: "All black", to indicate the color he would use.

'Zahara's surprise.

Interior of an inn', 1900. Commission received by Sorolla to illustrate a luxurious edition of the 'Legends of Zorrilla'.

Like all black, it is the clothing of the character that is shown in the album of Japanese prints, one of those that Sorolla treasured.

The figure is not represented in a volumetric way, as would be done in the West, it is a black plane that marks the difference with other planes of representation.

When Sorolla was born, the influence of

ukiyo-e

(Japanese prints) already permeated the canvases of the Impressionists.

He, as a cosmopolitan man and painter, was not going to stop including this in his works.

Thus, in the background of Agustín Otermín's portrait (1892), he represents a Japanese screen lacquered in black and with decorative motifs such as plants and birds that stand out against that tone.

That is one of the essential roles of him.

“It is the basis for other colors to stand out more.

Black is not the lack of light, but rather increases it and gives it power”, explains Reyero.

Although widely traveled and a great connoisseur of foreign artists both before and contemporary with him, Sorolla is still a Spanish creator and black is inherent in this tradition.

The influence from Velázquez is constant in his portraits, sometimes it is especially highlighted, as in

María dressed as a Velázqueña

(1905) or in

Quiquet Pons-Sorolla with a Velázque costume

(1920), which could be seen in

The Happy Age

, the exhibition former museum.

His contemporary Ignacio Zuloaga is seen in

El segoviano

(1907).

He ends the exhibition with some little-known works that refer to Goya's

Black Paintings

: the oil paintings on cardboard that he was commissioned for a luxurious illustrated edition of the

Legends of José Zorrilla

, specifically,

Zahara's surprise, romance of 1481

, whose destination was printing, hence the similarity of all the tones, because reproduction techniques were not yet very advanced.

The way of representing the naked bodies in one of them is striking in this painter.

Proof that black has always been in Sorolla's palette is a natural study of Clotilde, which served as a preparatory drawing for

Clotilde in a Black Suit

(1906), and which, printed on T-shirts and bags, forms part of

the museum 's

merchandising

for years.

As Banksy would say:

The Gift Shop Exit

.

And there, incidentally, you can browse the catalog of the exhibition, where, in addition to the curator's ideas, you can read two texts by Estrella de Diego and Isabel Clúa that bring Sorolla (closer) to modernity.

'Portrait of Manuel Bartolomé Cossío' (1908).

Joaquin Sorolla.