What happened to the post-truth?

Or better: what is the state of truth in the West today?

I admit that it may be a difficult reflection in the middle of summer, but this is also a time of calm, and calm invites reflection.

So if, by any chance, you wonder about what we call the truth, I suggest you think, for example, of the Putin regime's communication offensive since it invaded Ukraine, its systematic falsehoods, the repression of dissent or its scandalous rewriting of history.

I guess they see where I'm going.

Of course, the lies didn't go away in the US either when Trump lost power.

A good part of the Republican Party continues to talk about the “stolen election” by the Democrats, and ridicules the work of the congressional investigative commission on the January 2021 assault on Capitol Hill,

speaking without blushing of an attempt to divert public attention from the truth.

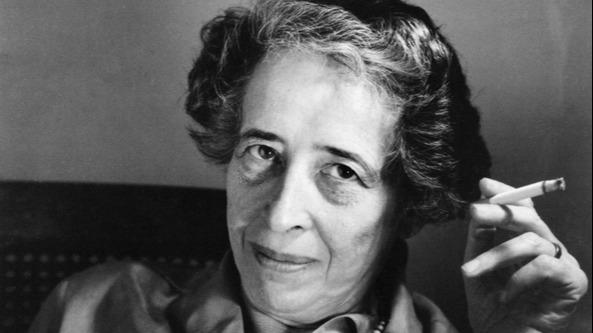

And in the face of such examples, it only occurs to me to return to the work of Hannah Arendt, perhaps the best leading thinker for these troubled times.

More information

Hannah Arendt keeps thinking

The author of

Truth and Lies in Politics

, a text that first appeared in

The New Yorker

in 1967, described lying as an action that is part of human freedom, its totalitarian variant being the loss of that which makes us distinguish it from the truth.

But where to locate ourselves today with these coordinates?

Because it seems clear that we are facing a second wave of post-truth, that phenomenon that appeared in 2016 with the stories of Brexit and the famous "alternative facts" of Trump, which even then cried out for an urgent rereading of Arendt.

When Trump shouted in the middle of the campaign that "I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot someone and I would not lose voters",

The origins of totalitarianism,

written in 1951, it offered us the keys to understand that the tycoon was not a simple political candidate for the Republicans, but the leader of an incipient mass movement.

When the White House spoke of “alternative facts” to deny the empirical evidence showing that Obama's inauguration had been much more massive than Trump's, Arendt helped us understand that movements thrive on the destruction of reality. , since they evoke a false but consistent world, “more adequate to the needs of the human mind than reality itself”.

The promise of returning to an idyllic past offers security and roots, the irresistible guarantee of a possible desire that makes us capable of denying reality itself.

Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, meeting in 2018. Photo: Getty

Today, the fictitious world invented by Putin appears in the form of "there is no war" but (as his spokesmen insist) a "special operation", a subterfuge that allows us to insinuate that Russians and Ukrainians are the same thing, a single people, showing Incidentally, the leader's Luciferian ability to, in Arendt's words, "isolate the masses from the real world."

Hence this superlative propaganda based on Soviet nostalgia and the arrogance of the old empire, on the glory of a past that allows it to compare itself to Peter the Great and affirm, almost painfully, that "we had no choice" but to act in Ukraine.

His propaganda seeks to produce a single truth on which no opinion can be formulated, a new objectivity "as real and untouchable as the rules of arithmetic."

If, for Arendt, the public sphere is that plural space, visible to all,

where freedom can develop, autocratic propaganda grips it in a repressive frame that tries to impose a single truth.

In democracy, we discuss and talk about what is happening in the world;

in a totalitarian regime, propaganda lies are 'woven around a central fiction'.

Think, for example, of the insistent appeal to a supposed “brotherhood” with Ukraine while its schools and hospitals are bombed and civilians executed as a strategy of control.

The important thing is to act and react according to the norms of that fictional world, romanticizing the war or spreading the narratives that legitimize it.

in a totalitarian regime, propaganda lies are 'woven around a central fiction'.

Think, for example, of the insistent appeal to a supposed “brotherhood” with Ukraine while its schools and hospitals are bombed and civilians executed as a strategy of control.

The important thing is to act and react according to the norms of that fictional world, romanticizing the war or spreading the narratives that legitimize it.

in a totalitarian regime, propaganda lies are 'woven around a central fiction'.

Think, for example, of the insistent appeal to a supposed “brotherhood” with Ukraine while its schools and hospitals are bombed and civilians executed as a strategy of control.

The important thing is to act and react according to the norms of that fictional world, romanticizing the war or spreading the narratives that legitimize it.

Journalists Isabeau van Halm and Michael Goodier explained in

The New Statesman

how the Putin regime uses images of Russian soldiers helping Ukrainian children, creating the narrative of that "little brother" being helped.

For his part, the writer Peter Pomerantsev told

The New York Times

that more than three-quarters of Russians believe they need “a strong hand” to rule the country, someone to protect and discipline the people, and how that is precisely the story the Kremlin often uses to describe Putin.

The equation is clear: the tyrannical truth is imposed through propaganda, which ends with the public sphere, whose disappearance deprives people of a referent of reality.

Thus, reading Arendt helps us to accurately identify the totalitarian overtones that stain Putin's regime with increasing force, its willful disconnection between discourse and reality.

Remember the mass celebration of the 8th anniversary of the annexation of Crimea, when the Russian president spoke of the need to "liberate the population from genocide", insisting on describing the massacre as a "liberating" mission.

His rhetoric refers to Arendt's explanation of mass following: the unwavering adherence to the leader, the same that evokes Trump's maxim ("I could shoot someone and not lose voters"), is conjured from the proposal of a world coherent in the face of the uncertain and chaotic reality.

Putin offers an ideologically consistent narrative in which all the pieces of the puzzle fit.

The repetition of key ideas, the slogans coming out of the mouth of a strong leader, give the masses that feeling of rootedness, creating that alternative reality where verifying the facts is useless because something much more powerful than reality is offered: the certainty of a world that gives meaning to uprooted lives.

the same one that evokes Trump's maxim ("I could shoot someone and not lose voters"), is conjured from the proposal of a coherent world in the face of the uncertain and chaotic reality.

Putin offers an ideologically consistent narrative in which all the pieces of the puzzle fit.

The repetition of key ideas, the slogans coming out of the mouth of a strong leader, give the masses that feeling of rootedness, creating that alternative reality where verifying the facts is useless because something much more powerful than reality is offered: the certainty of a world that gives meaning to uprooted lives.

the same one that evokes Trump's maxim ("I could shoot someone and not lose voters"), is conjured from the proposal of a coherent world in the face of the uncertain and chaotic reality.

Putin offers an ideologically consistent narrative in which all the pieces of the puzzle fit.

The repetition of key ideas, the slogans coming out of the mouth of a strong leader, give the masses that feeling of rootedness, creating that alternative reality where verifying the facts is useless because something much more powerful than reality is offered: the certainty of a world that gives meaning to uprooted lives.

Putin offers an ideologically consistent narrative in which all the pieces of the puzzle fit.

The repetition of key ideas, the slogans coming out of the mouth of a strong leader, give the masses that feeling of rootedness, creating that alternative reality where verifying the facts is useless because something much more powerful than reality is offered: the certainty of a world that gives meaning to uprooted lives.

Putin offers an ideologically consistent narrative in which all the pieces of the puzzle fit.

The repetition of key ideas, the slogans coming out of the mouth of a strong leader, give the masses that feeling of rootedness, creating that alternative reality where verifying the facts is useless because something much more powerful than reality is offered: the certainty of a world that gives meaning to uprooted lives.

Arendt may not be useful for

fact-checking

or elucidating the world based on tweets, but her work helps us to decipher the emotional reactions that propaganda provokes in us, and to identify the values it promotes.

It also speaks to us about the democratic referent as an interpretive counterpoint to authoritarian regimes, about the need to preserve a public space where it is possible and desirable to confront our opinions, and question the inevitable claim of all authority (here, there, yesterday, now and always) to monopolize the story of the truth.

50% off

Subscribe to continue reading

read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/MNACP55MFZEWDPW5ELRNS5IENE.jpg)