Four funerals, as if they were acts in a play, allow Damon Galgut (Pretoria, 59 years old) to go through the recent history of South Africa in

The promise

, the 2021 Booker Prize-winning novel, now published in Spanish by Libros del Asteroides.

"That structure was the first thing that was clear to me," explained the author this Monday in an interview with EL PAÍS in Madrid.

The family drama of his novel, set against a South African backdrop, has at its center a small house on the Swart family farm, the home of their black servant, Salome, who raised the children and cared for the family. mother during her illness.

“A friend told me a story like this, they promised to donate a house to the black woman that she had cared for her mother and it took decades to solve it;

in the end, in that case, they were eaten up by debt and there was nothing to leave him, ”he confesses.

More information

African literature was always there

Galgut speaks softly and exudes something melancholic and calm.

He has been on a promotional tour of Europe for six weeks and has another six to go.

"The Booker is a very noisy award and it's my turn to make some noise now, too," he says with a resigned and happy air after receiving the most prestigious award in English literature after having been nominated twice before.

He lives in Cape Town, but grew up in Pretoria, the place where

The Promise

takes place .

“I hated that place, it was a horrible place to grow up because the whole

apartheid machine was there.

.

There were military and bureaucratic uniforms everywhere and that somehow defined the mentality.

There was also something Calvinist, like from the Old Testament”, he recalled.

Galgut's father was Jewish, but her mother left him and her next husband was “a violent

Afrikaner

”, which somehow sums it all up for the writer.

His memory of Pretoria is also imbued with the two years of military service he performed there.

“My experience was not like that of Anton's character in the novel, I worked in an office.

I complied because I didn't have money or help to leave the country, nor was I brave enough to face six years in prison for insubordination, ”he clarifies.

The faith professed by the deceased in his novel changes: from the Judaism that the Swarts' mother embraces in her last years of life and that infuriates her husband, to the Catholicism of the eldest of her daughters, going through the fervor with a pastor-preacher and oriental philosophies imbued with a

new age

spirit , which seduce the wife of the firstborn.

“I thought that if all funerals were the same it would be literary uninteresting, but besides,

The Promise

is about white South Africans and I wanted to portray all their faiths.

apartheid

_

it had a component of religious fervour: the system was planned as if its conservation were a sacred mission, because we were the last ones to fight, what they described as terrorism, a force that would end religion, that would impose communism, that would bring darkness” , He says.

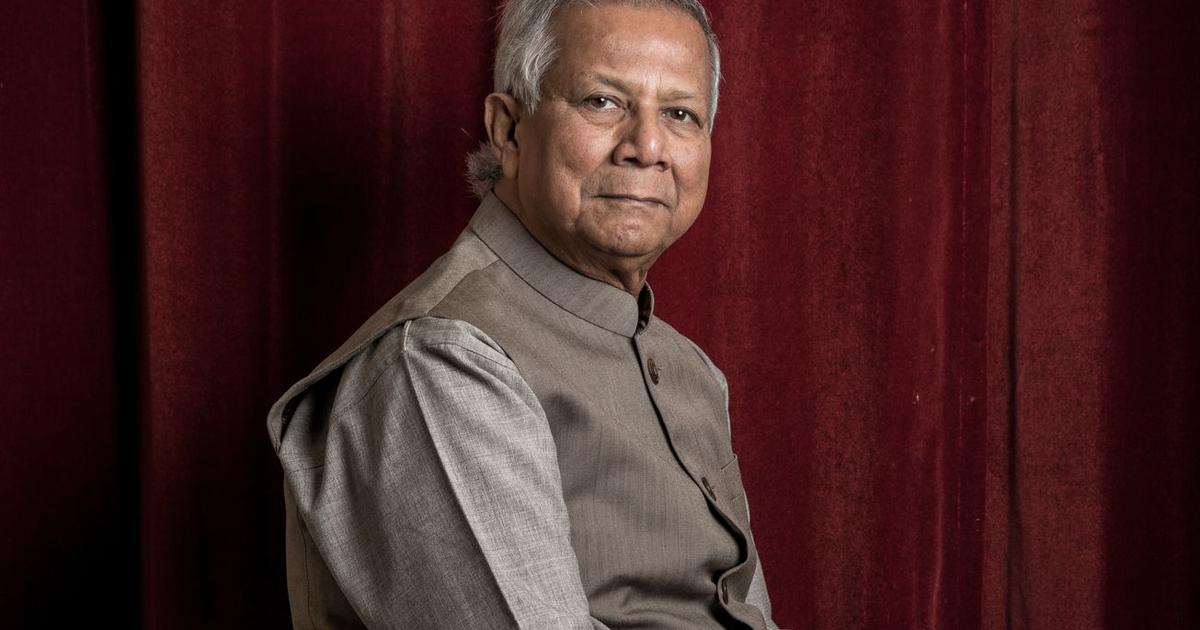

Damon Galgut, at another point in the interview. INMA FLORES

Apartheid fell in what

seemed

like a sudden breath — “I never would have believed it possible when I grew up” — and there was a moment of hope and optimism, the author evokes: “It seemed that in the 1990s the country would finally put aside racial categories.

But I am sorry to report that South Africa today is as deeply divided racially as ever before."

The historic 1995 rugby world championship final won by South Africa is remembered in

The Promise.

“In those years there was goodwill on both sides, many whites were willing to give up their privileges and blacks were willing to forgive.

It was a very important change, but deep down things did not change.

The economic gap is huge and that inequality has sown discontent, anger, bitterness and mistrust”, says Galgut.

The truth and reconciliation commission, in which victims and executioners offered their testimonies before the public to try to achieve restorative justice after

apartheid

, is also mentioned in his novel.

“The country needed symbols at that time of change, symbols like Mandela himself.

And that commission was also more symbolic than real: few people participated and for political reasons a pardon was offered.

Is that a way to process the past?” asks Galgut.

“The trauma in South Africa has not been expressed.

Most of those who were in the army during

apartheid

He did not speak, nor did the black children who grew up in those neighborhoods with the military pointing at their heads.

It is a deeply traumatized country that would need many years of therapy.”

Is writing able to help?

“Some things have been written and documented, but there continues to be an enormous silence and repression that keep the trauma alive.

I think that explains the dramatic rate of violence that the country suffers, something that goes beyond the streets or the ghettos, that occurs inside the houses, in all social classes and without distinction of race.”

Galgut does not believe in the transformative power of books —"novels do not change the world, but rather offer a testimony of what it feels like to be a human being at a specific moment"—, but he does acknowledge that novels in South Africa have helped to unearth some things and cites

Disgrace,

by Nobel Prize winner JM Coetzee.

“It talks about something that if the book didn't exist, it wouldn't be discussed.

And if the book comes out at a dinner, the anger is guaranteed.

That book is very loaded because it touches nerves that we are not in contact with.”

in

the promise,

Galgut says he wanted to reflect the blindness that afflicts white South Africans: "They don't see what it feels like to be a black South African, they really are oblivious to that reality of poor people."

The renunciation of privilege is at the heart of his book, and the characters take different positions, but not even the little Swart knows very well how to do it.

“Skin color is a destiny in South Africa, and you can't help being white or from the middle class.

It is impossible to escape, that is why the solution can never be individual, but rather it is the State that must direct the change, although now there is no will, no vision, no plan”.

He has not wanted to give a conclusion in his novel, nor offer a closed ending.

“It is easy in fiction to touch the emotional side of the readers,

offer a kind of catharsis that ends when they close the book, and they no longer need to think about the problem.

I resist that."

Subscribe to continue reading

read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber