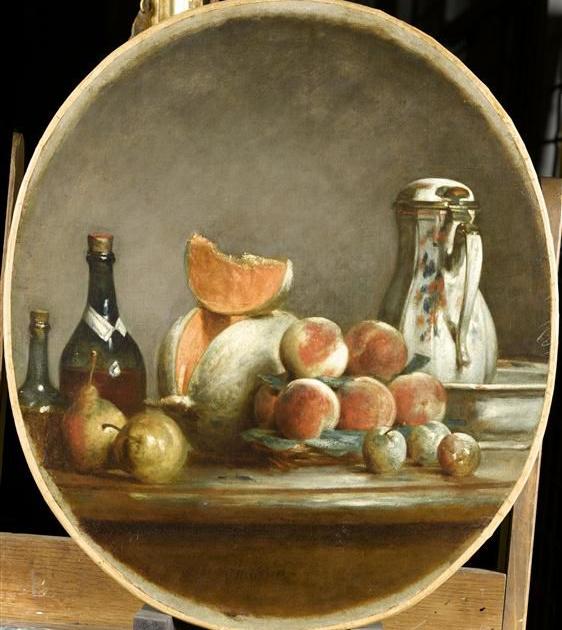

The recipe is well known.

A quince, a cabbage and a cucumber.

Dangling carrots, an open orange, and rotting lettuce.

And, sometimes, an hourglass in a corner or even a disturbing skull, which reminded of the dire fate that awaited the viewer of each painting.

The still life was never considered an important genre, on a par with historical or religious painting, nor with landscape or portraiture.

And yet, the simple arrangement on the canvas of these banal elements, such as fruits, vegetables, flowers, musical instruments and household items, continues to fascinate many centuries later.

Each still life contains a mystery, a shadow of melancholy that causes a small pang in the heart.

“An anthropological truth”, prefers to point out the art historian Laurence Bertrand Dorléac,

Things.

A history of still life

, which can be visited at the Louvre Museum in Paris until January 23, 2023.

'Still Life with Watermelons and Apples in a Landscape' (1771), by Luis Egidio Meléndez. PRADO NATIONAL MUSEUM

'Still Life', image of a still life on video by British artist Sam Taylor-Johnson.Sam Taylor-Johnson

'The five senses and the four elements' (1627), by Jacques Linard Jacques.Mathieu Rabeau / RMN-GP

'Six shells on a stone table' (1696), by AS Coorte.RMN / Grand Palais

'Still Life with Vegetables' (1610), by the Flemish painter Frans Snyders.Photo Wolfgang Pankoke (Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe)

'La deserte' (1640), by Jan Davidsz de Heem.

'The Lemon' (1880), by Manet.Patrice Schmidt / RMN-GP

'Melancholy of an afternoon' (1913), by Giorgio de Chirico.Jean-Claude Planchet / RMN-GP

'Natura morta' (1944), by Giorgio Morandi.Bertrand Prévost / RMN-GP

'Grisaille à l'espadon' (2022), by Miquel Barceló. David Bonet / ADAGP, Paris, 2022

'1st day in quarantine.

Brooklyn, New York' (2020), by Nan Goldin.Nan Goldin / Marian Goodman Gallery

The exhibition opposes the traditional definition of the still life, which emerged throughout the 17th century in Flemish and Dutch art, in the face of the ban on religious-themed images imposed by Reformed Protestantism.

This made many painters take refuge in genre scenes, daily vignettes for the taste of a new bourgeoisie that was beginning to replace the State and the Church in the role of artistic patrons.

This format received the name of

stilleven

(or quiet, silent life), a term that in Catholic countries was "badly translated" as still life, as the curator points out, more in favor of calling it painting of objects or things, another name prosaic but also more precise.

The imperfect translation and the oxymoron that it provoked inspired certain misunderstandings about the characteristics of the genre.

In reality, the inert objects in these paintings are very much alive.

Despite their ordinary appearance, they provide fundamental information about each era, about the beliefs, desires and fears of their owners, about cultural differences and the different attitudes of men and women when faced with the dilemmas of existence.

"If the genre arouses so much fascination, it is because it is not reduced to a morbid meditation on our disappearance, but is often a fundamental ode to life," says the director of the Louvre, Laurence des Cars, in the catalog of

Things

, a title indebted to the novel by Georges Perec, an acute X-ray of the consumer society.

'Still Life with Fruits and Vegetables' (circa 1602), by Juan Sánchez Cotán, Spanish loan at the Louvre exhibition. Abelló Collection

The show's thesis, like that of the writer, is that things transmit ideas and feelings, beyond the lazy link of this genre to the passage of time and inexorable death.

The Louvre's ambition also involves expanding the geographical and temporal borders that have delimited this genre: it existed not only in Renaissance and Baroque Europe, but throughout the world and at all times.

In 1952, another exhibition on the history of the still life organized at the Orangerie made it clear that still lifes had existed since classical Greece.

This exhibition goes even further: through 170 works from all periods, the Louvre maintains that still lifes appeared in Neolithic caves and later spread to Egyptian and Mesopotamian culture, as witnessed by engravings and mosaics exhibited in the museum's rooms. .

The pairings are unexpected and exciting: Georges de La Tour's

Penitent

Magdalene

by candlelight with Christian Boltanski's photographs;

a

vanitas

Baroque along with another by Gerhard Richter and yet another, in video format, by Sam Taylor-Johnson, with fruit that spoils in real time.

Or the canvas on two tax collectors by Marinus van Reymerswaele in the 16th century attached to the self-portrait of Esther Ferrer vomiting euros at the height of the entry into force of the single currency, in 2002. The Louvre opposes another stainless commonplace: the one that ensures that still lifes disappeared from painting during the thousand years that the Middle Ages lasted.

He refutes it with an idea that, well thought out, seems to be out of the box: that the objects of domestic life did not disappear from the paintings, although they were always at the service of a religious allegory.

Since the 16th century, they reappeared as a reminder of the lightness of life, not as far removed from Christian morality as is often said:

The Louvre opposes the cliché that says that still lifes disappeared during the thousand years that the Middle Ages lasted.

The genre survived, albeit in the service of a religious allegory.

With the emergence of the market, this critique of accumulation took on a political reading, which the Parisian museum highlights with a quote from Marx, who was always clear that objects were fetishes, inscribed on a wall.

“It is not an anti-materialist exhibition.

The relationship of artists with objects is ambivalent, there is as much criticism as spell”, the curator specifies, despite everything, using examples such as the fish markets in Dutch painting or the canvases by Erró, icy portraits of abundance in Western postwar times.

A dark room brings together Goya, Rembrandt and Zurbarán portraying a handful of dead animals.

On the left, Géricault confronts them with an oil painting that shows the dismembered limbs of a human corpse, likened to a mammal torn to pieces in a butcher shop.

Are the lives of each other worth the same?

“The work of Goya and Géricault arises at the time of the Napoleonic wars, massive conflicts where humans became objects for the first time.

For me, art does not enter modernity with Manet, but with those two painters who reflect the suffering of civil society”, points out Bertrand Dorléac.

'Still Life with Ribs and Lamb's Head' (1808-12), by Goya, and 'Study of Severed Arms and Legs' (1818-19), by Géricault.RMN-Musée du Louvre

Still life was later resurrected in the work of the Impressionists, who turned it into a symbol of peace and quiet at a time of rampant industrialization —there are Manet's asparagus or Cézanne's Provencal pears—, while the avant-garde accentuated the ashen complexion of this kind, as if it were the omen of something terrible about to happen.

This is demonstrated by the artichokes painted by De Chirico or the innovative variants of the genre by Picasso —his magnificent paintings of objects against the light— or Miró, whose exhibition includes an almost psychotropic still life from 1937 that MoMA has lent.

Taking up a thesis formulated years ago by the New York museum, the curator also includes

ready-mades

of Duchamp, like the urinal or the bottle rack, in this new taxonomy of still life.

And also some even more surprising works, that no one had linked to the genre until now, such as Van Gogh's room in Arles, Jacques Tati's sarcastic criticism of modern furniture, the photos of Martha Rosler in a kitchen converted into a women's prison or installations made with Bazooka brand chewing gum by Félix González-Torres.

Despite their heterodoxy with respect to classical still lifes, all of them are based on the symbolic dimension of everyday objects.

The denouement of the tour comes with a sequence from

Zabriskie Point

, by Michelangelo Antonioni: the tremendous explosion imagined by the protagonist in which all the properties of the mansion where she is staying are blown up to the rhythm of Pink Floyd guitars.

And, with them, the image of the refrigerator filled to the brim with which the consumer society forced us to dream.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber