The poet Kenneth Koch, in one of his poetry workshops for elementary school children.Helen Weaver (Courtesy of the Kenneth Koch Literary State)

The poet Kenneth Koch (1925-2002) seemed like a nice guy.

His poetry was playful and luminous, highly imaginative, celebrating the simplest things in life and language.

In the photographs that can be found on the internet, he always appears smiling (even in one in which he appears to be arrested by a policeman).

His students at Columbia University regarded him as a stimulating, witty, and passionate professor of literature.

And he dedicated not a few efforts to bring poetry closer to that group so frequently forgotten and vilified: children.

"Once the language exists, there is also the impulse to play with it," he wrote.

The most beautiful thing about his way of teaching poetry to the little ones was respect.

He did not underestimate them: he offered them pieces by some of the most important poets of his time or of the poetic tradition (William Carlos Williams, John Ashbery, William Blake, Wallace Stevens, Rainer Maria Rilke or his beloved Federico García Lorca).

“He thought it was a problem to give children bland, cheesy, infantilizing poems”, says the editor Aníbal Cristobo, “his idea was to propose the texts of these poets based on an axis that could question the little ones”.

He did not understand the border between children's poetry and what we call adult poetry.

Thus, he encourages his tiny pupils to write (in what he called "tasks") inspired by the great poets, but using motifs from their world, their dreams or their desires.

For example, from the famous poem

Just to tell you

, where Williams confesses that he has eaten some plums that someone kept in the fridge for breakfast (Forgive me / they were delicious / so sweet / so cold), Koch proposes to write about things that like to do, even if they are poorly done.

About not regretting too much.

“Koch spreads the idea that poetry is not so much a literary genre that has to be adapted to different audiences, but a way of looking at and relating to the world”, says the poet Claudia González Caparrós.

What mattered not so much was formality, or talent, being a good or bad poet, nor learning names, dates, rhymes, and metrics (as so many attempts have been made to teach poetry, without much success), but imagination and the desire to explore and have fun.

“Once I dreamed that my friend was a carrot and I was a cucumber,” wrote Ilona Barbuka, one of her students, inspired by a dream.

'Just to tell you', by the boy Andrew Vecchione inspired by William Carlos Williams

Thanks for the ants you left in my bed.

This is just to say thank you for giving me the sunset

purple on my birthday

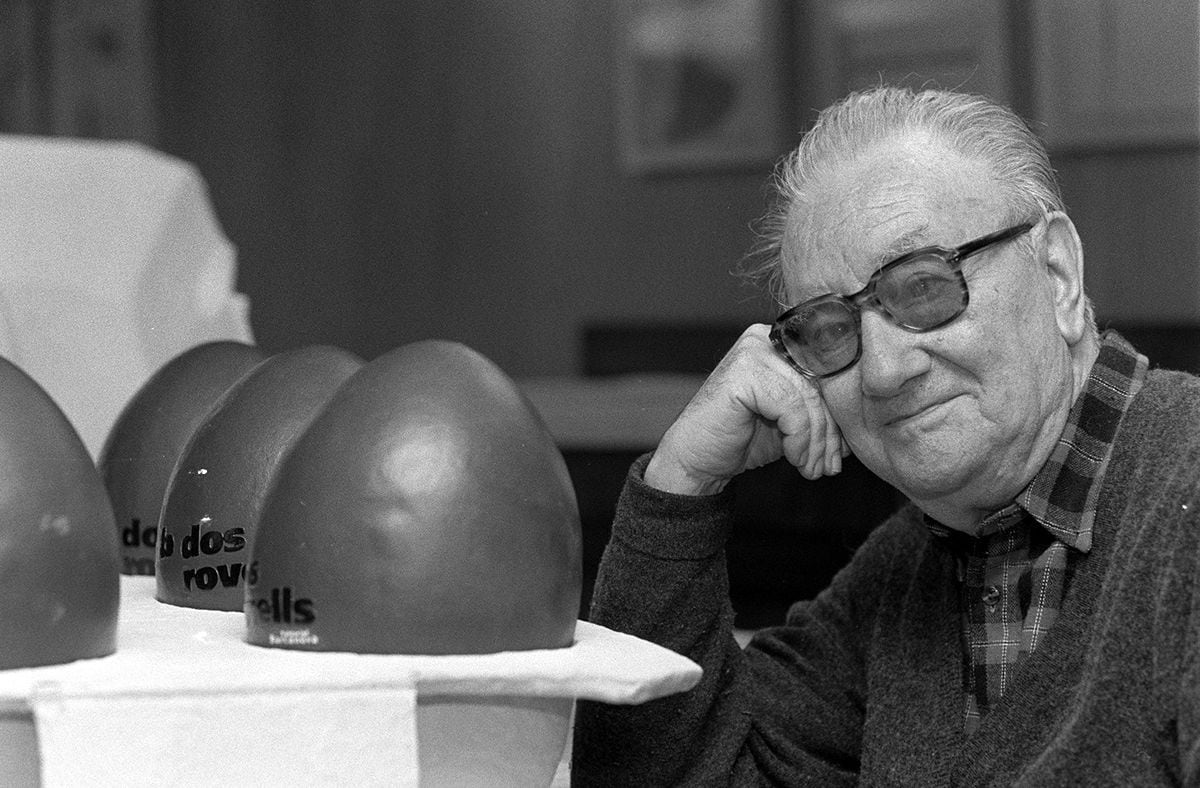

The poet Kenneth Koch in one of his classes. Courtesy of Kriller71 publishing house

poetry in public school

Koch began giving poetry workshops to elementary school students at a public school in New York (Public School 61, in Manhattan) in the late 1960s, but later expanded his scope to give workshops in different countries.

From his extensive experience came two successful books that spread his methods to a large number of schools:

Wishes, Lies and Dreams: Teaching Children to Write Poetry

(

Wishes, lies and dreams: teaching children to write poetry

), published by Harper Collins in 1970, where literary “homework” predominates, and

Rose, Where Did You Get That Red

?: Teaching Great Poetry to Children

.

), published by Vintage Books in 1973, which comments on the works of established poets and their way of inspiring children.

His teaching activity reached the pages of

The Wall Street Journal

,

Life

,

Newsweek

or

The New York Review of Books

, and the public readings of his crazy short disciples reached the same spaces where the established poets recited.

From the mixture of the two aforementioned works, which greatly helped to spread another way of teaching poetry, the recent Spanish synthesis is formed:

An ant is the beginning of a new universe

(Kriller71), edited by González Caparrós and Cristobo, where the two books have been merged, taking into account that some of the exercises did not make sense when translated into Spanish.

Poem by the girl Marion Mackles, based on "lies"

I am as green as the grass.

I am on the leaf of a tree.

I'm in New York on a flying cranberry.

The mud is beautiful.

The rain is ugly.

I'm on a vine.

I am snow.

I am snow in Spain.

I am rain in Spain.

I am the sun in Spain

I am a cloud in Spain.

I am in Spain.

I am Spain.

Koch proposes writing collaborative poems (as was done in ancient Greece, in medieval Japan, or as the surrealists did), poems based on wishes (beginning with the formula "I would like...") or on what he calls "lies ”, that is, in counting things that do not exist.

He proposes to write about "something that shouldn't be pretty, but you secretly think it is."

At the end of his volumes he gives advice for poetry teachers.

The most important: reading poetry.

“One thing that encouraged me was how playful and imaginative the children's speech was sometimes,” Koch writes, “they said true things in surprising new ways.”

Koch's pedagogical adventures and the poems of his students lead the reader to an anthology of his own poetry, collected in Spain in

Perros ladrando en la nieve

(Kriller71), edited by Jordi Doce.

Thus it is discovered that Koch's poems are not so different, saving the distances, from those that he inspired in his workshops.

“Perhaps that is one of the keys: Koch did not have to change the chip, what he brought the children to the workshops was the same thing that he and his colleagues produced, many times with similar procedures”, says Cristobo.

The New York School

His "colleagues" were the poets of the so-called New York School;

in fact, more than a school, it was a group of friends that emerged in that city in the 40s and 50s. Among them, as the most visible head, the enormous (and strange) John Ashbery;

also, lesser known, Frank O'Hara (who died young, at 40, hit by a beach buggy).

Also, Barbara Guest or James Schuyler (see the anthology

The New York School of Poetry

, published by Alba).

“These people brought a lot of oxygen to poetry, moving it away from academicism and brainy stuff,” says Cristobo (although reading some of the authors, like Ashbery, is anything but easy).

They loved the French surrealism of Roussel and Apollinaire, rejected the academicism of

New Criticism

, had connections with the abstract expressionism of Pollock and De Koonig, which at that time made New York the artistic center of the planet (taking the place of Paris), and with the neo-dadaism of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.

'Four ways to look at a wolf', poem by Joseph Scifo inspired by Wallace Stevens

A wolf in a book looks like a snarling wild dog.

A werewolf and Frankenstein together are a wolf.

A wolf is like Godzilla when his tummy hurts.

A wolf is like a long-haired hippie.

The times helped Koch's activity: "By the late 1960s it was clear that good modern poetry did not have to deal with a lofty theme presented in lofty diction framed by rhyme and meter, which are the main stumbling blocks for poets." children when writing poetry”, writes the poet Ron Padgett in one of the forewords.

Not only that: Koch began teaching in 1968, a convulsive moment in the world where hierarchies were questioned, new worlds were sought, new ways of doing things, a certain horizontality, and creativity and imagination were valued (which is wanted bring "to power" as read on the graffiti of the Paris riots).

Perhaps the most curious thing about Koch's activity is to verify that the texts that can be dark and mysterious to adults, and make us repel poetry, do not have to seem so to children: Koch believed that it was a mistake to present the poems like a riddle to be deciphered, and that we had to enjoy them more freely, even if we don't fully grasp their meaning: let them flow in language and approach them not so much from the intellect as from the emotion.

And the little ones know how to do it: "It's nice to see how the dictatorship of meaning has not yet reached children," concludes Caparrós.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/2I2OVXYIZRARVK4X4A37KHSD34.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/FS5FDPA2QFAPPP3M22RRTDN2II.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/GOC4OMOSPRGHBC3AGTSKUSEWDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/TGZ4TIGSGJFWBISZ2FULJ7BYDQ.jpg)