The presence of Spanish art at the São Paulo Biennial really started in a big way, in 1953, with an anthology dedicated to Pablo Picasso that included

Guernica

, already then a world-famous painting.

He had a hard time convincing the artist but he gave in and the painting made its penultimate trip before settling in Spain.

He arrived in Brazil by boat and had to be carried freehand in the rain by the assemblers at the gates of the exhibition pavilion in the Brazilian metropolis, after the truck that was transporting him got stuck in a quagmire.

The man from Malaga participated, but not as a Spaniard, but with the French delegation.

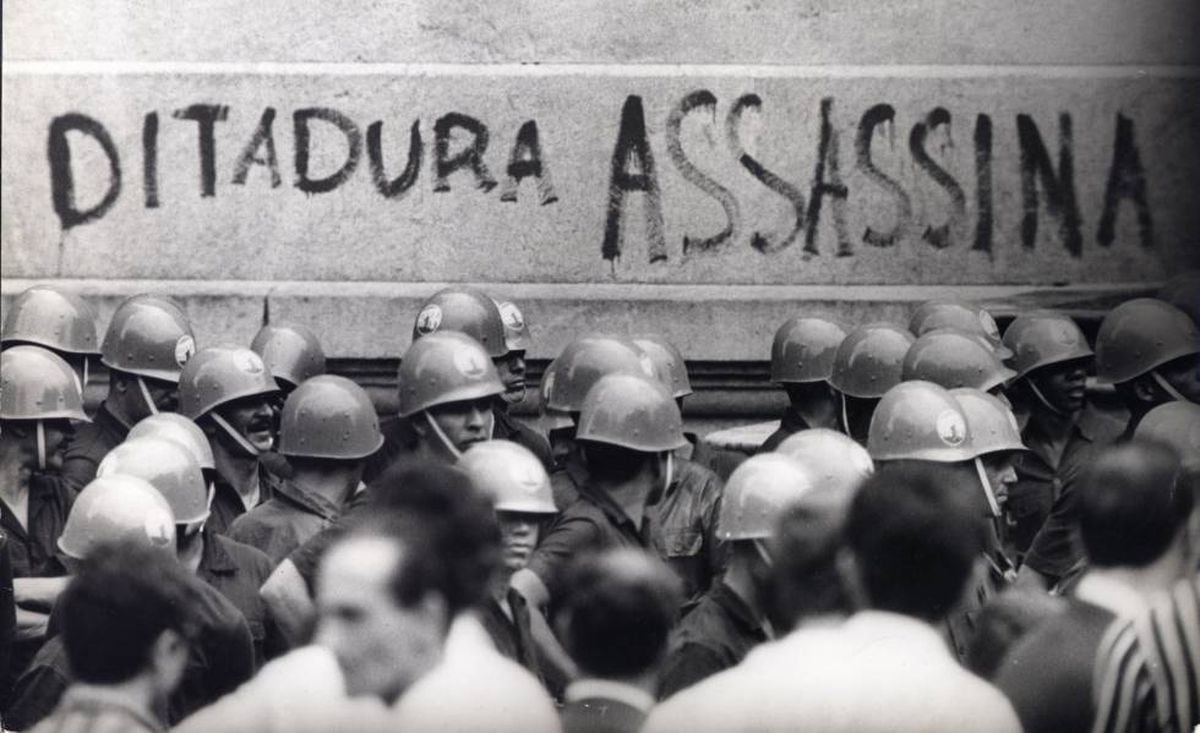

However, the Franco dictatorship soon understood that this international event for contemporary art was an unbeatable propaganda tool to present itself as what Spain was not then, an open and avant-garde country.

And he got to work.

The Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP) inaugurated last Saturday an exhibition, organized by the Niemeyer Center of Avilés (Spain), which brings together some 40 works by Spanish artists awarded at the Brazilian Biennial between the fifties and the end of the dictatorship.

Through paintings, sculptures or engravings signed by Rafael Canogar, Jorge Oteiza, Antoni Tàpies, Modest Cuixart, César Olmos, Joan Ponç, among others, the Spanish presence and its propaganda facet are reviewed.

Entitled

Vuelta al revés del revés

, after a verse from the song

Sampa

by Caetano Veloso, the recently inaugurated exhibition, which remains open until June 4, is a reduced version of another that could be seen a few months ago in the Asturian city.

The Genoveva Tussell police station explains that the Franco dictatorship (1939-1975) enthusiastically embraced the São Paulo Biennial from the second edition because “it wanted to offer an image of modernity, with art at the level of what was being done internationally and with which he also won prizes.

And that mattered much more than the fact that the artists could slide a critique of the regime.”

It compensated the Franco authorities.

And to the artists, also because, adds the specialist, there were very few scholarships, Spain was also culturally isolated and that was practically the only way to make themselves known internationally.

The work 'Pies Vendados', by Darío Villalba, in an exhibition that reviews in São Paulo the Spanish participation in the different editions of the Biennial. Lela Beltrão

An emblematic example of this dialectic between art and political power, the work titled

Los revolucionarios

, by Rafael Canogar, which won the highest prize, the Itamaraty, in 1971, when Francoism was already facing student strikes but Brazil was still immersed in the years of lead of the regime of the generals, determined to stop the advance of communism.

That year, Spain participated with this work, a hybrid of painting and sculpture that includes a soldier and a guerrilla fighter with a Castro cap among several figures who advance with impetus towards the viewer.

The Brazilian award for

Los revolucionarios

, awarded by an international jury, served to appease the discontent and neutralize the dismissal of the Spanish official in charge of selecting the works, explains Tussell.

“Ceferino Moreno publishes a text in the 1971 Biennale catalog about how Spanish artists are concerned about the problems that afflict society and modern man, such as repression, the lack of freedoms, etc.

Rafael Canogar told us that when the Ministry of Foreign Affairs read that text, they fired him.

But, in between, the news of the prize arrived, which somewhat compensated for the minister's displeasure.

And all drew a thick veil.

Canogar was reunited with this work, which was deposited in São Paulo after the Biennial paid him $2,850, in the Spanish exhibition, held at the Centro Niemeyer in Avilés, in the only building that the Brazilian Óscar Niemeyer built in Spain.

The São Paulo Biennial was born in 1951 promoted by a Brazilian businessman of Italian origin, Ciccillo Matarazzo, who was inspired by the Venice contest.

His wife, Yolanda Penteado, was instrumental in convincing Picasso to agree to send Guernica to Brazil, a decision that upset MoMA.

A good part of the MAC USP collection was created by incorporating the awarded works in the different editions of the Biennial, whose next edition will be between September and December.

A man looks at the work 'Painting number 4', by the artist Modest Cuixart. Lela Beltrão

Turned Upside Down Inside Out

also includes some works by exiled artists.

And an award-winning Tàpies in 1953. It is a youth painting entitled

Asia

that recreates a dreamlike atmosphere and reflects the influence of Joan Miró.

Also noteworthy is

Hanging Feet , from the

Encapsulados

series

by Darío Villalba, which belongs to the collection of the Reina Sofía Museum.

A piece that is at the same time a photograph, a sculpture and a mobile because it is suspended in the air.

According to Tusell, the Francoist Ministry of Culture officials in charge of choosing the works were always attentive to new international trends in order to present a selection in tune with the most avant-garde currents.

But the prize for the uniqueness of the pieces now exhibited in São Paulo would probably go to

The Myth of the Cave

, by José Luis Verdes, from 1975. "It is extraordinary, we are at the end of the dictatorship, at a time when video art installations are beginning to gain importance," says the curator.

Spain is committed to an installation inspired by the myth of Plato, made up of a closed and dark space with various types of silhouettes and some light projectors into which the visitor enters, creating a sophisticated game of shadows.

On this occasion, only a couple of the silhouettes and the extremely detailed handwritten instructions of the artist have been transferred to São Paulo, who in any case spent a month in the Brazilian city to assemble it himself.

The original installation rests in the warehouses of the Reina Sofía.

Tusell points out that, despite the fact that mounting it today would be complex, half a century later, the mechanism works.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/J5IWSET3B5HNDLKVIWAF74V77E.jpg)