After a couple of decades of relative oblivion, James Ivory (Berkeley, California, 94 years old) stars in a kind of renaissance. The Oscar for best adapted screenplay in 2018 for Call Me By Your Name, the first of his long career, caused a new generation to approach his work. "These rediscoveries have always happened, in all the arts. The difference is that it happens to me without having died yet," jokes the director from his home in Claverack, a nineteenth-century mansion in the Hudson River Valley, in the State of New York. On the contrary, Ivory is very much alive. In addition to his memoirs, Solid Ivory, published just over a year ago, two documentaries are being prepared about his life and work: Merchant Ivory, about his relationship with his producer, Ismail Merchant, and In Search of Love and Beauty, which will feature the opinions of the actors he turned into stars, such as Hugh Grant, Emma Thompson or Helena Bonham-Carter.

The filmmaker rides the wave with the documentary he has co-directed with Giles Gardner, James Ivory, the long journey, which has just been released by Filmin. In it, he re-watches the images filmed during the trip he made to Afghanistan at age 32 to shoot a film financed by the Rockefeller family, which he never got to edit. Going back to the year 1960 allows him to relate what Kabul was like at the time, "a city of mud houses, before the arrival of the Soviets, the Americans and the Taliban." But also narrate his youth in Oregon, his sexual awakening – in dialogue with the homoerotic story of the Mughal emperor Babur, which also fascinated E. M. Forster, whom Ivory has taken three times to the cinema – and his encounter with Merchant, starting point of one of the longest collaborations in the history of cinema and a sentimental relationship of four decades. The documentary works as an epilogue to his long career and seems to respond to the will to tell his side of the story with transparency after many years of half-truths.

Two photographs of James Ivory during his trip to Kabul (Afghanistan) in 1960, reflected in the documentary 'The Long Journey'.

Ivory's life can be read as a story of phalluses. At least, that's how the director himself narrates it in his autobiography, in which he reviews all the virile members he has encountered. "Well, it wasn't that many. Only two or three...", he smiles. Its pages deny it. There's that of his best friend from school, who tried to get into his mouth without touching the inside of his cheeks "to avoid germs." There is "the pink and hanging foreskin" of another, furtively observed in the gymnasium, which reminded him of "the ancient marble statues" of Greek art manuals. There's "the heavy-looking dick" of Ted, another colleague, "of the garden hose variety." And, finally, also "the pink dick that combined with the cheeks" of the writer Bruce Chatwin, with whom he had an affair.

It is surprising that Ivory, master of the most refined period cinema, that of gagged desire and demure sexuality of the Victorian and Edwardian eras, who did not admit his love affair with Merchant until his death in 2005, is released in this way in the final stretch of his life. "I'm not ashamed. I didn't want to be insincere or shut up," he replies. In reality, his films were not as repressed as is often believed. His debut, The Young Couple (1963), already included a homosexual character, as well as Autobiography of a Princess (1975), The Bostonians (1984) or a classic of queer cinema as Maurice (1987). "I was raised in Catholicism, but when it came time to choose between religion and my sexuality, I decided to leave the church. I am not envious of young gays, because I also experienced my desire freely. I have lived my sexuality without fear and without guilt."

"I found out he was adopted in the schoolyard. It was the fault of the nuns, who were tremendous gossip."

From his childhood, Ivory understood that he was a different boy, with drawing skills and an almost innate interest "in interior design". While the other children wanted balls, he asked Santa Claus for a dollhouse, which he dedicated himself to decorating with care, as reflected in the documentary. In addition, he had been adopted by a sawmill owner and his wife. "I found out in the schoolyard. It was the fault of the nuns, who were terrible gossips and had told some children," he recalls. "It was a shock, but I got over it. My parents loved me madly. They told me that, of all the children, they had chosen me. My adoption left a mark on my psyche, but it wasn't negative." Was the sophistication of your cinema a response to the economic hardship of the Great Depression? "We were not poor, even though there was poverty around," he says. "The films of the time were pure escapism: films that took place in sophisticated places, all that glamour of MGM. And that did influence me."

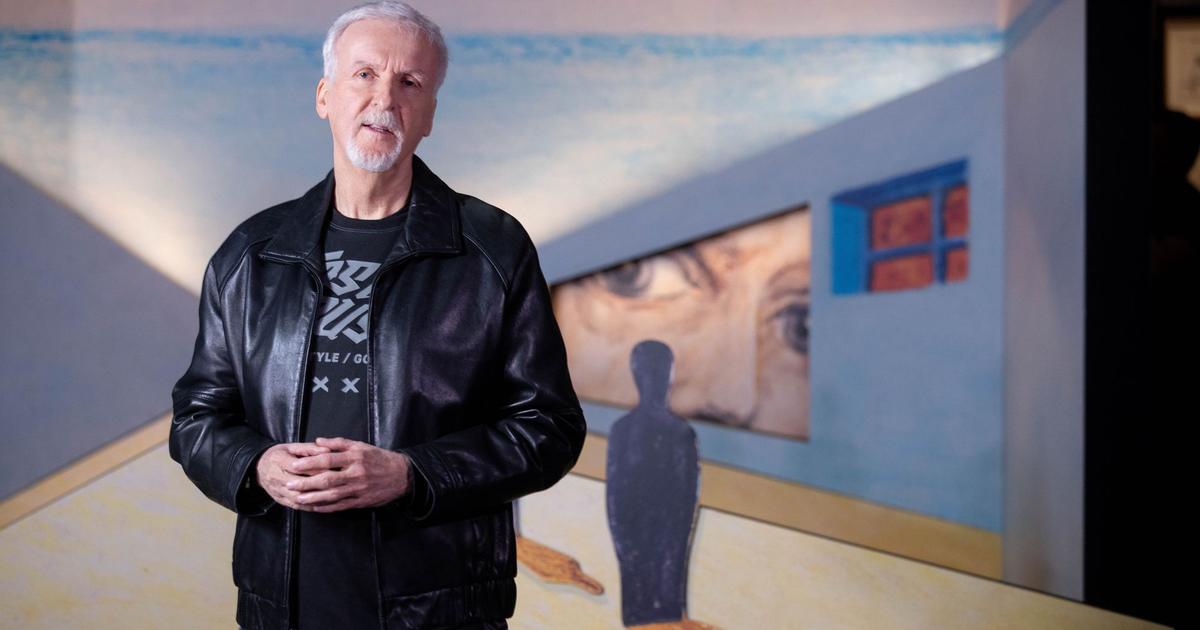

The American director James Ivory, in a picture of the sixties.

It is curious that an American from the West Coast, a Muslim from Bombay like Merchant and a German Jew like Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, screenwriter of a score of his films, defined the British period cinema of the late twentieth century. Did being foreigners benefit them? "Probably. It was a strange recipe, yes. Maybe it helped us to be outsiders in a place like England, so averse to change and so marked by tradition," he says. The film he is most proud of is not part of the glorious trilogy formed by A Room with a View (1985), Return to Howard's End (1992) and The Remains of the Day (1993). "It's not the best, but I really like the last one I shot, The City of Your Final Destination. With her I got to the place I had always wanted to go to as a director."

"If I don't make films, it's not because I don't want to, but because the insurers won't let me. They're afraid I'll die in the middle of filming."

His most underrated film? "There were three: Slaves of New York [adapted from Tama Janowitz's book], Jefferson in Paris and Surviving Picasso. The critics destroyed them and they were box office failures, but I think they are very good." Which would be the worst? "I hope I don't sound cocky, but I like all my movies." And what would have changed if I had directed Call Me By Your Name, as originally planned? "They removed a couple of scenes that I thought were important," he replies. One of them spoke of the arrival of AIDS, but Luca Guadagnino suppressed it, preferring to shoot an idyll in the classic sense, set in a paradisiacal garden, "without opposition or setback". "But Luca did a good job. People always suspect I dislike that movie, but I don't. I liked it a lot," he rectifies.

James Wilby and Hugh Grant, in 'Maurice' (1987). Moviestore Collection Ltd / Alamy

Helena Bonham-Carter, in 'Return to Howard's End' (1992). Moviestore Collection Ltd / Alamy

Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson, in 'What Remains of the Day' (1993).

Leelee Sobieski and Jesse Bradford, in 'A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries' (1998).

Ralph Fiennes, in 'The Russian Countess' (2005).

Charlotte Gainsbourg, in 'The city of your final destination' (2009).

One wonders why he has not returned to directing since 2009, being in top form. "Next week I will be 95 years old. People my age don't make movies. And not because I don't want to, but because the insurers won't let me. They are afraid that I will die in the middle of filming," he says. Even so, he has one last project in hand: the television adaptation of To End Eddy Bellegueule, the book by Édouard Louis, which will move the action from northern France to the Oregon of his youth. "I've written the first two episodes and I'd like to direct some," he says. On the other hand, his project to take Shakespeare's Richard II to the cinema by the hand of Tom Hiddleston will not see the light. "We couldn't raise the money. I thought there would be interest in the UK, but there wasn't," he laments. "Although I think if Ismail had been alive, we would have shot it five years ago. He always got everything. The problem is that it's gone." And then the conversation fades to black, in every sense of the word.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Read more

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/QAXTOV3HBVDK3ANOR7E4MXOEYU.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/QMMLZZZRT5DBBKJ3BCMUK42HQQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/OANTGMPBGJEHXKFEIVC3F4QCA4.jpg)